Saving face: ‘Spare parts’ man Brenton Cadd changes lives

Need a new nose, eye or ear? Meet the ‘spare parts’ man changing lives.

In January 1970, a young man joined the facial prosthetics department at the Royal Melbourne Hospital. As an apprentice dental technician, Brenton Cadd, 17, began learning on the job how to fix people with disfigurement so that they might be freed of shame or embarrassment. His mentor in the four-man department was Cliff Wellington, a signwriter by trade who’d served in the army as a dental technician. He had a painter’s eye for detail, and in 1945 he’d transitioned into the nascent field of facial prosthetics. Returned servicemen missing ears, eyes and noses were in dire need of some form of camouflage to help them blend into a crowd. Through a peculiar mix of technical ability and artistry, Wellington was an Australian pioneer who passed onto his young charge his aptitude for working on small, intimate canvases.

Today, a framed photo of a smiling Wellington sits prominently on a shelf near the door that leads into a workshop managed by Brenton Cadd. For 46 years he has devoted his life to a single workplace and this single task. Through the use of silicon, empathy, paint, patience, titanium, plaster and good humour, he is a leader in a highly specialised field that employs only a handful of people across the country. He is a quiet achiever whose work takes time, and whose time at the Royal Melbourne Hospital is much nearer its end than its beginning. What will happen after he sees his last patient is unclear, for what he does for them is nothing less than life-changing.

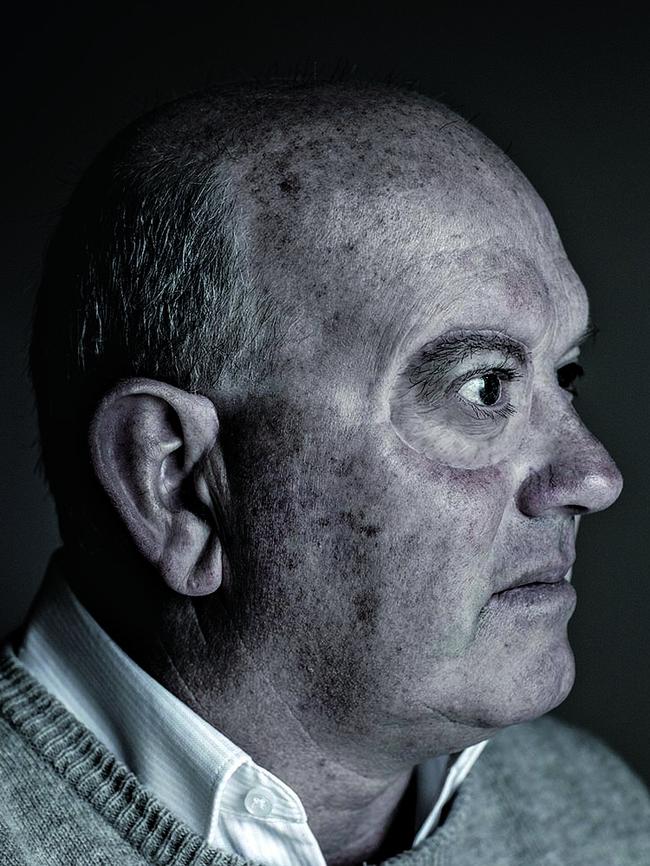

You could pass Cadd in a crowd without a second glance. If you are a long-time fan of the Hawthorn Football Club, you are likely to have done just that at a home game. He does not invest too much time in his appearance and wears polo shirts with a breast pocket in which he keeps a small notebook he calls “the brain”. It helps him remember his many pressing tasks. He is bearded, with kindly blue eyes that have looked upon thousands of patients who, whether they are able to articulate it or not, are relying on him to co-create a new identity for lives riven by the trauma of looking different from everyone else.

Here he is, on a Wednesday afternoon in mid-August, looking squarely at a patient whose left eye was removed due to cancer. Geelong retiree Pamela Flatt, 68, sits on a high-backed dentist’s chair while her husband and daughter perch nearby. Flatt’s left eye socket is now covered by a skin graft and her disguise is a pair of thick-framed spectacles, with the left eye coloured solid white. In the near future she will no longer have a use for these glasses as a transformation led by Cadd is slowly taking place. Around the edge of her eye socket, screwed into bone, are three abutments made of pure titanium. Soon, a silicon-based prosthesis will be clipped into place with magnets.

Flatt is a grandmother of six and a great-grandmother of three. Since her nine-hour operation to remove the cancer over a year ago, she has hardly locked herself away from the public eye: in fact, she has just returned from a trip to Thailand with a girlfriend, where she rode on an elephant. “Why not?” she reasons. “Life’s too short.”

Despite her positive outlook, the metal implants have drawn attention. “Kids are looking at me like I’m an alien or something: ‘That lady’s got funny things in her head!’ ” she says. “They weren’t bothered until I had those things put in.” Nerve damage means that she can’t feel the titanium plate behind her skin, nor Cadd’s hands as he uses a small torque screwdriver to tighten the abutments. He then covers her eye socket with two layers of a rubber-like material for making a cast and lets it set on her face for a couple of minutes. Just like having a wax job, she quips.

While she sits still and silent, Flatt’s daughter steps in to take a snapshot for posterity. “Someone usually takes a photo,” Cadd says, smiling. With care, he removes the cast, which will later be used for a custom-made mould that fits the exact contours of her eye socket. He excuses himself to retrieve from next door a beautifully hand-crafted eye prosthesis for a younger woman, complete with thick lashes, a realistic brown eye and dark eyeliner. It’s a work of art. “That’s what we’re aiming for,” Cadd says. “But we’re still about five visits off something like that.”

The appointment concludes after an hour, but before Flatt heads back to Geelong she turns to Cadd and jokes: “I can’t be a one-eyed Cats supporter then, can I?”

Brenton Cadd’s professional life is contained within two small rooms, a consultation space and workshop on the seventh floor of the hospital’s city campus. The tight workshop is filled with bubbling steel pots, thermos-like beakers and machines for mixing solutions and moulds. Dozens of lifelike ears, eyes, noses and fingers are mounted on plaster backings. These aren’t display models; they’re moulds taken from actual patients. On the top shelf is a handful of plastic skulls, some pinned by silver splints to show outdated methods of applying dental prosthetics. On the wall above Cadd’s workspace is a framed certificate, dated 2015, in recognition of his 45 years of service to the hospital. Two seats down, Greg Peart’s 2008 certificate recognises his 25 years of service and between these two men sits Jeff Magallanes, 39, the youngest of the trio.

Throughout Cadd’s career, half a dozen apprentices have learnt from the tiny facial prosthetics team, only to be informed at the end of their training that the hospital does not have the budget to offer them full-time work. With few tertiary education or employment pathways available, it is something of a dying art. “It’s funny, isn’t it? More and more people are losing their noses to cancer, but none of the universities are interested in offering courses,” says Genevieve Juj, director of allied health at Melbourne Health and Cadd’s manager since 2008. “I think 3D printing put a kybosh on it, too.”

Last year, the department saw 217 patients. Two-thirds were affected by cancer, the remainder had experienced trauma or congenital disfiguration. Together, the three men helped mould, design, fit and maintain 63 eyes in 2015. These are the most expensive pieces, costing about $7000 each; only the eyeballs are created off-site, by a specialist ocularist based in Camberwell. The trio produced 72 noses (about $4500 each) and 72 ears ($4000) last year, as well as a few miscellaneous prosthetics such as fingers, toes and nipples. For those patients who make an appointment through the public health system, there is no charge.

It is, however, a time-consuming and labour-intensive art: on average, an eye prosthesis requires eight to 10 visits before a piece can be considered finished, as the team painstakingly ensures that the skin tone and hair colour are matched to each patient. For Cadd, Peart and Magallanes, the process can take up to 40 hours per prosthesis.

David Murray, 58, sits in the consulting room waiting for a touch-up colouration appointment on a Thursday afternoon. He’d had an adenoid cystic carcinoma that had wrapped itself around his optic nerve. With the mass out, doctors soon identified another type of cancer that required radiotherapy, which would kill his right eye. “My wife and I decided the eye’s got to come out,” he says. Cadd ducks in and out, occasionally handing the prosthetic to his patient and stepping back to consider the fit and colour against his skin tone. “Brenton and his team are unbelievable,” says Murray. “He’s my man. The doctors gave me life, but Brenton gave me existence.

“My wife accepts me,” he says, smiling. “She’s more worried about me being overweight or bald than about the eye. Some days, I’ve got to think to remember which one it is, to be honest.” Immediately after surgery, he wore an eye-patch, then frosted glasses, but neither felt anywhere near as natural as what Cadd created for him.

When Murray queries whether anyone else in Australia does this work, Cadd replies: “There’s not many of us about.” He counts on his fingers two technicians based at The Alfred Hospital and the Mercy Private Hospital in Melbourne, as well as a few in NSW, Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia. Cadd’s team also receives occasional referrals from Queensland, the Northern Territory and Tasmania.

“It’s a bit of a treasure, this place,” says Murray, smiling and shaking his head. “But I don’t want this guy to have too much work!”

If being born without a left ear is bad luck,losing one to a freak accident as a teenager might be unluckier still. This is what happened to Colleen Murray (no relation to David) who was thrown through the back window of a car during an accident near Ballarat one morning in 1961, long before seatbelts were mandatory. The tiny 15-year-old skidded along the bitumen on the left side of her face. Following months of skin grafts and operations she returned home but did not go back to school. Instead, she began working as an office clerk at an engineering firm while covering her disfigurement with a scarf.

Following the car accident, her life’s path forked. She said farewell to her plans to become a midwife; farewell to favourite pastimes such as swimming and playing basketball. Farewell to wearing earrings. Beneath her scarf was a prosthetic ear that she glued on every morning, but she was so self-conscious about her appearance that she never revealed it in public. Once her thick brown hair grew back, she wore it long for decades. Framed photos in her home near Geelong show her smiling at the camera. That smile, however, hides an emotional scar that ran so deeply through her life that she only ever told one person outside her immediate family about the prosthetic ear — her ex-husband, who never wanted to talk about it either.

“I kept it secret,” says Murray over coffee and biscuits in her living room. “I didn’t want people staring at me. I never told my children. It was my problem, so I kept it to myself. It made me very strong.” For 54 years, Murray shut the door on her past life. She has known Brenton Cadd for more than 30 years. She would occasionally visit the Royal Melbourne Hospital to have her prosthetic ear cleaned and touched up with paint. A silicon prosthetic was made for her at one stage but she never wore it. She was sure it was her lot in life to glue on her false ear every morning, in the privacy of her home, before she could face the world.

A couple of years ago, though, on a routine check-up, Cadd handed her a titanium implant model, with the magnets that lock into place with a satisfying click, and left her alone for 10 minutes. At first she was unmoved, but as the minutes ticked by it dawned on her that it was time to try a new approach. When Cadd returned, she told him: “Yes, I want one.” So began an 18-month process that involved having her head scanned at Deakin University in order to 3D-print a silicon version of her right ear, which was used as the basis for Cadd and his team to recreate an exact mirror image that now clips onto the left side of her skull. Unless you knew she had a prosthesis, there is almost no way you’d be able to tell.

Now 69, Murray revels in keeping her hair short and wears earrings every day. “Brent is the reason I had this done,” she says, beaming. “I was born with two ears; I always wanted to have two ears. Brent mends people so that they can live normal lives. He’s one in a million.”

“He has to fiddle, fix and build,” says Cadd’s wife Deb, 62. “Nothing leaves this house without being pulled apart and fiddled with to see if he can get it to work.” Deb has found that if she uses the words “prosthetic technician” to describe his job, people look confused, which is why she’s developed a short, satisfying answer: “He makes spare parts.” It’s succinct and truthful, of course, but it belies the depth and complexity of the work itself. Having learnt about facial prosthetics throughout their marriage of 41 years, Deb has become somewhat inured to the truly transformative nature of his handiwork.

At 64, he remains tight-lipped about any plans to retire. When Deb recently asked her husband this very question, he replied that he might keep working until he’s 82. “For years and years, I’ve called him the quiet achiever,’’ says his youngest sister Judy Cadd. “He might seem a bit blasé about it all, but he gets things done in his own way.”

After so much time spent toiling in the shadows of the Victorian public health system while helping thousands of patients to feel more comfortable in their own skin, his children reckon it’s time for the quiet achiever to be celebrated. His 31-year-old son Michael says that when his father retires, he’ll be petitioning for something significant in the Royal Melbourne Hospital to be named after him. Imagine that: large-scale recognition for an artist who doesn’t want his work to be noticed. A public gesture to a man who has devoted his entire career to helping Australians with disfigurement hide in plain sight. The Brenton Cadd Wing. It’s got a nice ring to it, don’t you think?