Michael Lewis The Blind Side Moneyball Big Short

Author Michael Lewis (Moneyball, The Big Short) explains how luck and lucidity have made him ridiculously happy.

One summer, when Michael Lewis was about 13, his parents sent him to a tennis camp in New Hampshire. “We went to a lake called Echo Lake. And Echo Lake is, like all New Hampshire lakes, dark and freezing,” he says, eyes sparkling at the memory. “I swam out and 30 yards off the shore dived down to the bottom and grabbed whatever I could grab.” His trophy felt like damp paper. Returning to the surface he opened his palm and found… a $20 bill. Seriously? “Seriously,” insists the author of Moneyball, The Blind Side and The Big Short. “It was a soggy $20 bill. I thought, ‘That’s just the kind of thing that happens to me’.”

Four decades later, Lewis has no reason to see life any differently. His outrageous luck is a “running joke” with those who know him. It helped Lewis to stumble unqualified into a plum job at Wall Street’s top trading firm in the early ’80s, so that he was perfectly positioned when that world imploded to write an explosive book about the working culture that made the 1987 crash possible, which in turn earned him an even larger fortune than he’d made selling bonds.

He was only getting started. Having struck gold with his first literary effort, Liar’s Poker, Lewis swiftly became, without any apparent strain, that rare nonfiction author whose name alone propels a new hardback to the top of the bestseller charts. His 15 books to date, tackling subjects as diverse as high-frequency trading, fatherhood and the evolution of tactics in American football, have sold more than nine million copies. Three of them have become films that either won or were nominated for Oscars. One of them, The Big Short, was described by Reuters business commentator Felix Salmon as “probably the single best piece of financial journalism ever written”. Another, Moneyball, helped to spread a revolution in baseball management and has been hailed as one of the most influential books in the history of sportswriting.

His readers couldn’t care less that he says he has never had an original thought in his life. They love him for his bravura storytelling, for the compelling real-life characters he unearths and for the way he takes big, complex, data-rich subjects such as the 2008 financial crisis, or the hidden workings of the human mind in his latest book, The Undoing Project, and makes them not only intelligible but riveting.

His real good fortune might be his personality. Lewis, 56, is by his own admission lazy, selfish and easily bored. This is another stroke of luck, because these character traits have proved to be a “tactical advantage in doing what I do”. He doesn’t waste time on anything uninteresting. “I find things that grab me and if they grab me enough I write a book.” He is rarely burdened by self-doubt or social embarrassment, handsome in a lived-in sort of way and “rich enough now not to have to think about it”. Fortunately, he is also charismatic, generous and, judging by the number of literary subjects he talks about who have become close friends, steadfastly loyal. He does not appear to take himself too seriously and when amused he throws his head back and lets out a high-pitched machinegun burst of laughter. You could be envious, but then what would that achieve? As Lewis reminds me, envy is “the one sin that you don’t get any pleasure out of”. Easy for him to say.

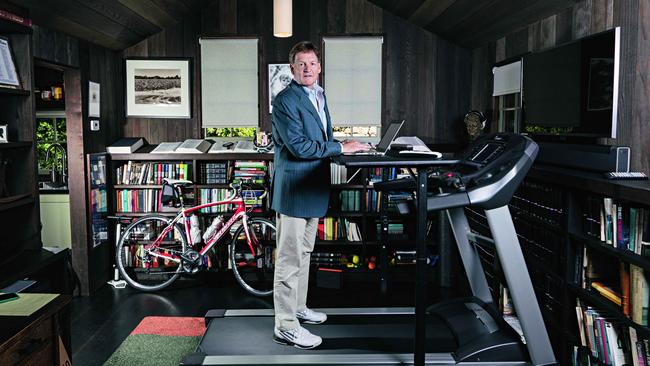

“Would you like to see the house?” he asks when I arrive at his writing cabin on a leafy lane in the hills of north Berkeley, a university town near San Francisco. He moved to Berkeley almost 20 years ago with his third wife, photographer Tabitha Soren. Inevitably, they were incredibly lucky with their house-hunting. “We knocked on the door, introduced ourselves and they said, ‘We’ll sell it to you.’ They wanted to move out.”

His cabin is about the size of a standard hotel room and crowded with armchairs, a running machine, an expensive-looking bicycle and the memorabilia of a life lived to the full. There are dictionaries with magnifying glasses arranged on reading ledges by the windows and, below them on the bookshelves, stacks of baseball annuals, the complete works of Evelyn Waugh and the eight-volume Encyclopaedia of Psychology that Lewis leant on heavily for The Undoing Project.

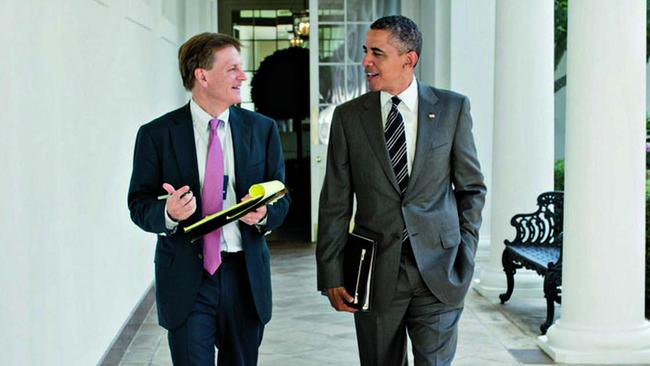

In the bathroom there’s a cartoon from Politico showing congressional leaders reading The Big Short after they all kept recommending it to each other in public. A photo in the small kitchen area captures him as a schoolboy baseball pitcher. Two others show him with Barack Obama, whom he shadowed for six months for Vanity Fair.

Lewis has written all his books in this literary man cave since 1999’s The New New Thing, which explored the first internet boom. He does a lot of travelling for research, “going out and hunting material”. Then it is a matter of “dragging it back here and writing it”, he says. “Left to my own devices without children, which I was for a long time, I would start writing about 8 o’clock at night, end about four in the morning and sleep till one in the afternoon.” Instead, he does the school run most mornings (he has two daughters, Quinn, 18, and Dixie, 15, and a son, Walker, 10), then types fast but chaotically until family life intervenes again in the afternoon.

At the moment he has not written a word for four months. After his latest book he promised himself some time off, when nothing would get in the way of “being a proper father and husband and all that. And it’s kind of fun for a few weeks. And then I have an inalienable sense that I should be doing something. And then it gets worse, and worse, and worse,” until he does. When Lewis is in a writing phase he feels more alert to the world. When he isn’t, “There’s a satisfaction that I miss.”

He plans to start work soon on a long piece for Vanity Fair. That tends to be how his books begin. The magazine pays him $10 a word, which would be a fortune to most writers. To Lewis it’s “underpayment… it’s five times that for the books”. The idea this time is to look at how President Trump is managing a part of the federal government (Lewis won’t say which part), because he thinks that Trump, the neophyte politician who spent his life wheeling and dealing, is actually “the least competent businessman we’ve ever had in the [Oval] Office”.

Lewis is not a knee-jerk liberal – he voted for Reagan and has gone “back and forth” over the years – but his contempt for this “dumb” president is undisguised and he thinks Trump might not last much longer in the White House. “I think he’s mentally kind of unhinged and unpredictable. And he’s gonna continue to be. He’s not gonna conform to the behaviour that’s usually exhibited in that office. So he is a more frightening character now to me than he was when he got elected. Just slightly. Because he was pretty terrifying when he got elected. The situation, though, looks like it has the potential to play as comedy, in a way I didn’t quite imagine when he was elected. It’s imaginable to me that he’ll quit in a couple of months. Society’s finding ways to defend itself against him. And getting better and better at it.

“The courts seem to have seen their importance. The media’s in a golden age. Right? So there are all these defensive institutions that seem to get stronger and stronger, and his approval ratings are going down.” What Lewis dreads is a Wag the Dog type incident that tilts public opinion dramatically. “I worry that something happens that enables him to use people’s fear, or that he creates it. We may be more sophisticated than that now. I just don’t know. But if a nuclear bomb goes off in New York City, I don’t think we are.”

He has not approached the Trump team asking for access like he had with Obama, but he knows exactly what he’d ask for. “I’d want to be with him in those hours he’s tweeting. That’s the first thing I’d ask. I mean, they wouldn’t ever let it happen, but could I show up at five in the morning, or whenever it is those tweets start? Can I get there an hour before, make him coffee, whatever he has, be part of that routine? And then just watch him do it. Just the visual. And the piece would open with that. You could probably do a whole story just following a tweet. Following the consequences of a single tweet, right?”

Lewis is leaning forward in his red swivel chair, pounding an imaginary phone, pretending to be Trump. “He’s sitting there like, farting around, goes to the bathroom. In his robe, in his underpants. He goes boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, bang! He’s off. And then you leave him, and you just see the effects of this thing over a year. They never go away. They keep coming. Eighteen different other things will have happened because of it.”

Typically, Lewis’s books and articles originate in more unlikely places than the White House, with subjects who are often unaware that their stories are worth telling. The Blind Side, his book about tactics in American football, came about when a different project put him back in touch with a friend from nursery school. Visiting Sean Tuohy’s rich white family in Memphis, he wondered who the 193cm, 160kg black teenager at their house was. He turned out to be Michael Oher, a destitute schoolmate of their daughter’s, who they had rescued from a life on the streets and who would, with the family’s support, eventually become a Super Bowl-winning millionaire.

The Undoing Project was sparked by a review of Moneyball by two academics who pointed out that the author appeared to be unaware that its central thread – the statistics-driven approach to baseball pioneered by maverick manager Billy Beane – was rooted in the work of two eccentric Israeli psychologists decades earlier. This was true. At that point Lewis had heard of neither Amos Tversky nor Daniel Kahneman, whose collaboration from the late ’60s to the ’80s overturned the way scientists and economists thought about the way humans make judgments and decisions. In the process they profoundly affected fields as diverse as medicine, finance, politics, professional sport and the military – and provided the foundations for much of the thinking that Lewis’s work has explored over the years. Tversky died in 1996, but Kahneman was still alive and recently won the Nobel prize for economics.

A little later, Lewis mentioned the review over a drink with his regular “sounding board”, a psychologist at the university in Berkeley. Astonishingly, his friend had known both men and was still in contact with Kahneman, who turned out to live a mile up the hill from Lewis.

Gradually, over many long walks with Kahneman and a fact-finding trip to Israel together, Lewis extracted an extraordinary human story of two wildly different men who forged a friendship so intense that he came to view it as a platonic love story. “There is no argument about who the genius was… it was the two of them together,” he says. The dispute that will “never be resolved” is over who is to blame for the shattering break-up of their partnership once they both moved to the US. Was it Kahneman’s neuroses or Tversky’s insensitivity that doomed their partnership?

Lewis found it impossible to answer that question in The Undoing Project, and didn’t want to pick a side. Temperamentally, though, he says he can “completely identify” with Tversky’s “fantastic ability to do only what you want to do and nothing else”, as well as his appetite for risk, the ease with which he moved through life and his utter absence of social anxiety.

Only last week Lewis did something along those lines that “completely infuriated” his elder daughter. He had brought Quinn along to hear him read his work as part of a 2000-person charity benefit. He picked a passage “about having to give a sperm sample after my vasectomy, and I’m in the lab and there’s no bathroom to jerk off in. So I’m riding around Berkeley looking to hide in the bushes to do it, or a parking lot [because it has to be very close to the laboratory], and I’m describing this odyssey and it didn’t even occur to me to be embarrassed. I thought it was funny.” Afterwards Quinn refused to speak to him. Eventually she said, “Everyone I know was in the audience!”

As a child growing up in New Orleans, Lewis was “crazily happy” and a bit of a troublemaker. He had an affluent upbringing in an old Southern family descended on his father’s side from a judge sent to Louisiana by Thomas Jefferson after its acquisition from the French, and on his mother’s from James Monroe, the fifth US president.

He was not a high achiever at school, where he struggled to focus in many of his lessons. He preferred sport. “My position in the world is baffling to people who knew me as a kid, because they could never imagine I’d bother to write a book,” he says. Yet he made it to Princeton, where he studied history of art and felt instantly at home. “I was extremely social. Knew everybody. Loved it.” He didn’t distinguish himself academically until he became obsessed with his thesis on Donatello and the Renaissance in his final year. One of his professors called it “the best thesis I’ve ever had”.

“That was a turning point, that thesis, no question,” Lewis says. After that he became set on a writing career but was unsure how to get there and suffered “rejection after rejection after rejection”. Even his home-town newspaper, The Times-Picayune, refused to publish him. Trying for Wall Street jobs, he was unanimously rejected by recruiters, who felt that he “lacked commercial instincts”, so he ended up doing a masters at the London School of Economics.

Then luck intervened. A chance encounter at a black-tie dinner in St James’s Palace with the wife of a managing director from Wall Street trading firm Salomon Brothers led to a job offer. Once there, he cold-called the investment manager for a large bank, who it transpired adored New Orleans. They became friends and Lewis secured sole access to one of the bank’s most important clients, making himself indispensable. Meanwhile, he wrote about the industry for The Wall Street Journal under the pseudonym Diana Bleeker, part of his mother’s maiden name, until he was tracked down by the publisher father of the comic actor Chevy Chase, who pitched him the idea of a book.

“That was the end. It was right around the crash, October 1987. And I thought, at that moment, in my head, I was out… I remember walking around and saying, ‘I just gotta write everything down. Because this will all be material.’” Liar’s Poker made Lewis moderately famous and fantastically rich. He was 28 years old. Since then he has spent a lot of time thinking about money and the troubling effect that an obscene quantity of it tends to exert on people. “Their whole life becomes about the money. And they become more and more financially interested and obsessed. I have to guard against that a tiny bit in my life, and I catch myself doing it. Money can be a substitute for living. You just start measuring success by how much money you make and you just spend more time thinking about it.”

He strives to avoid that, and to let financial security free him to live life more fully. Most very rich people struggle to do that. “The norm is to feel like you’re important because you have the money, to give yourself all kinds of little passes about how you spend your life, and how you behave.” Trump is a case in point. “It seems to me his entire life has been about nothing but money,” Lewis says. He calls it “the money disease”.

Lewis’s own regrets are different. If he had to write a memoir, “There would certainly be places I was not proud of, but it wouldn’t be because of money. It would be romantic error. Just being less sensitive to my partners than I should have been.” Even before he was successful, he “ran through girlfriends a little roughly” because he “never figured out how to end a relationship gracefully”. He begins to count them off on his fingers. “I feel really bad about how I broke up with a high-school girlfriend, how I broke up with two college girlfriends and badly about one wife.” What happened? “When I smell death, I’m out. I don’t waste another moment.” In economic terms, he says, he has always been good at ignoring “sunk costs”.

By and large he is emotionally “very resilient”. Recently, though, he suffered the worst emotional blow of his life when his best friend from childhood died after a long illness. “If there’s one thing I could undo from my whole life, I would keep him alive.” Their relationship was on his mind as he wrote about Tversky and Kahneman. His friend died six months ago. Ever since, Lewis has been “sitting here waiting to write to his children about him and I can’t. Every day is a deadline I don’t hit. He was a really unusual cat and I just loved him.”

Saying this, he almost becomes hesitant, briefly. “Everything else, like bad marriages, are so kind of trivial, compared with that.” Otherwise, “It has been a charmed life. My wife says I’m the luckiest person she knows, sometimes with resentment.”

Lewis sees method as well as chance in his good fortune, though. “My parents made me feel like I was an incredibly lucky person, like good things happen to me. My mother, in particular, always helped me define myself as someone who, when I was handed lemons, turned them into lemonade. It’s the single trait I’ve tried to persuade my children to have, because something about how you filter the world has a huge effect on what happens to you. The opposite of that – ‘Bad things always happen to me. I’m not resilient. I turn lemonade into lemons’ – that’s a disastrous life.”

Most of the very successful people I’ve met seem to be driven by some inner resentment or dissatisfaction. Lewis is different: a contented, fulfilled and optimistic outlier. “I connected with Obama on this because Obama, deep in his soul, is a Hawaiian f..k-up.” The former president told Lewis that he “really could just do nothing”, but had concealed his inner beach bum by choosing a high-achieving path. “I related to that. I had a capacity to move through life without taking on any particular challenge, living and being happy. I put something on top of it that regulates it a bit, but I still have the capacity to do nothing.”

That’s not going to help people to envy you less, I say. And he shrieks with laughter one last time at the sheer ludicrous joy of being Michael Lewis.