Angie Scarth-Johnson’s climbing to the top of her grade

She travels the world conquering rock climbing records – and she’s only 12. The sky’s the limit for Angie Scarth-Johnson.

In 1976, a 14-year-old Romanian gymnast named Nadia Comaneci stormed into the Montreal Olympics with the first-ever perfect score of 10. Gymnastics would never be the same again. Comaneci did things that had never been done and in doing so vastly increased the level of skill, and the risks, for all those who would follow. She made gymnastics more spectacular and infinitely more dangerous. Greg Mortimer reckons the sport of rock climbing is undergoing a similar “paradigm shift”. Leading this revolution, he says, is a 12-year-old climber from the Blue Mountains, NSW, called Angie Scarth-Johnson. “She is breaking all the rules,” Mortimer says. “She’s just freakishly good.”

Mortimer, 65, is the doyen of Australian mountaineers and rock climbers, our Bradman of the steep pitch. He was the first Australian to reach the summits of both Everest, in 1984, and K2, in 1990, and the first of us to reach the top of just about every other significant big thing there is. He began rock climbing as a teenager, in the mid-1960s, scrambling up the Three Sisters at Katoomba in the Blue Mountains. In 2010, while on a rock climbing adventure with his son in a remote fjord in Greenland, as you do, he fell, breaking his back, eight ribs, smashing his head and heel, and collapsing a lung.

They don’t come any more hard core than Greg Mortimer. And yet, when he looks at what is happening in the world of rock climbing now it is with a sense of awe and excitement, and some trepidation, at the physical feats. The climbs now being executed are so intricate, difficult and torturous that “people are literally ripping the muscles from their bones in exertion”. The sport is pushing its participants to the limits of human physicality and concentration. “And Angie has tapped into all that – she’s leading it – and she’s only 12,” he says. “It really is incredible.”

Red River Gorge, in the US state of Kentucky – Daniel Boone country – offers some of the world’s best and most difficult rock climbing. Angie is here on a month-long climbing quest with her folks, Claudia, a social worker, and Tek, a plumber, scoping out two particularly troublesome climbs, Lucifer and Pure Imagination. Both are grade 34 climbs; if she manages to nail either she will equal the most difficult climb ever undertaken by an Australian female. A grade is measured by the degree of technical skill, endurance, power and level of commitment needed. The highest grade completed by an Australian male is 35.

To get this into perspective, good climbers who work at it for years, with three or four training sessions a week, may reach grade 25 or 26. A dedicated climber friend of mine says a climb of 34 is “just f..king insane”. The most difficult climb ever by any woman in the world is a grade 36 and 38 for a man. Angie is almost there. It’s like being one metre behind Cathy Freeman in the 400m at the age of 12.

She was seven when she began climbing and by the age of eight was climbing cliffs that can take years for mere mortals to conquer. At the age of nine Angie became the youngest person in the world to climb a grade 31, also at Red River Gorge, on a climb called Swingline. Last year at the age of 11 she climbed two grade 33 cliffs – a grade so difficult that only two other Australian women have ever conquered it. She was the second youngest person in the world to make a 33 and she is now currently considered the world’s best female outdoor climber aged under 16.

Is she nervous about attempting these grade 34 climbs that will put her within reach of the world’s best adult climbers? Not at all, says her mum, Claudia, telling me a story about an abandoned beagle they found in the campground at Red River Gorge, nicknamed Dogo. Angie loves animals and has been wandering around the campground each afternoon with Dogo, looking for someone to give him a good home. The fate of this dog has been troubling her – an insanely difficult rock face that a handful of people in the world can conquer, not so much.

Rock climbing is a combination of chess and gymnastics. It is both mentally taxing and extremely physically demanding – one foot on the wrong crevice can throw out the climb, six or seven moves down the track. Every single action has to be mapped out in the climber’s mind beforehand so that when an attempt is made there is a seamless flow. Hanging from the side of a cliff is physically exhausting and so to complete a successful climb every move has to be choreographed so there are no wasted movements.

“It is much like playing chess,” says Mortimer. “It is delightful in its intellectual raptures. It is extraordinarily consuming and quite cathartic and meditative. You are totally absorbed by that piece of rock in and around you.” Climbers will spend days, even weeks, attempting to scribble a narrative across a particular rock face.

For some reason, from an early age, Angie had a knack at being able to work through these complex puzzles – like a kid who can pick up a Rubik’s Cube and solve it in an instant – and an amazing body that can hold impossible positions.

“When I was little I started climbing a bunch of stuff around the house, trees and stuff like that,” Angie tells me. “And I kept falling off things and out of trees and Mum and Dad took me to a climbing gym where they thought I’d be safe. Straight away, as soon as I started climbing in gyms, I knew it was what I wanted to do,” she says. “If I could read books as well as I can read rocks, I’d be a doctor by now.” Maybe, like learning a second language or surfing, learning to read rocks is best done as a child.

She is also very strong, able to lift her entire body weight with her fingertips holding precariously onto a tiny ledge the width of a pencil. She has the hands and fingers of a bricklayer, craggy and calloused. “Whenever I go to my grandma’s house she complains about how my hands are too hard and is always trying to put moisturiser on.”

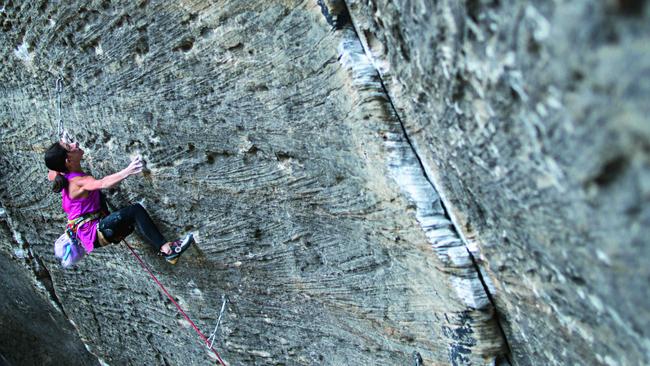

Watching Angie climb is mesmerising, her fingertips hooked into tiny crevices, called crimps, as she works her way across an overhanging cliff face. It might take 20 movements to move five metres to reach a larger hold, known as a jug, where she can have a rest and shake out the excruciating lactic acid build-up in her arms. It’s like watching an insect on a ceiling and wondering how it can possibly hang on. At times it is very painful and she has taught herself to endure that pain. When she gets into trouble, she’s learnt not to panic and to think, “OK, I am going to fall, but I am not going to die.”

It looks dangerous, but she insists it is safe because she is attached to rope connected to a bolt in the rock. “Climbing is not really as dangerous as some people make it out to be,” she says. “It is actually extremely safe. The chance of a bolt breaking is close to nothing. I have had rope burn and sometimes I hit the wall a bit hard when I fall but that is about it.”

It has helped in some ways that her parents were not climbers when she began (though they’ve since taken to it); she had to work it all out for herself. Claudia says that before Angie started climbing, she and her husband led a fairly sedentary existence. “Now we love hiking and we love being outdoors – we are always outside and off camping. Angie’s passion has really changed our whole family’s life.” They have two other daughters, an 18-year-old at university and a 25-year-old who works in Canberra. In 2012, the family moved from Canberra to Mount Victoria in the Blue Mountains; Claudia says it was partly for the tree-change and partly to allow Angie to pursue climbing. “It is not something we have pushed her into doing – she’s completely self-motivated,” she says.

In the lead-up to a climbing expedition, Angie will train three or four times a week. Her mum drops her off at the indoor climbing gym and she trains herself. She had a trainer for a bit but prefers to work it out alone. “I love to push myself,” Angie tells me. “I love the way it feels when I achieve something. I push myself because the more I push myself the better I get and that excites me and that makes me push myself even more… I’ve been doing this for nearly six years now and I haven’t got sick of it in any way. I can see myself being a climber (as an adult), travelling, maybe living in a van and climbing. For me, that would be better than any other job in the world. It would be amazing.”

Being a professional climber, at this stage, is still a dream; there are some professional climbers in the US and in Europe, but none in Australia. Angie has a small sponsorship from the sports company North Face but is reliant on the sacrifices of her folks, who are happy to travel with her. Last year they spent four months in Spain, living in a tiny village, while their daughter climbed; her mum trained as a teacher and for this long trip she did her schooling through distance education. Usually, though, they go for a month and Angie’s school will set her work and Claudia will supervise. “I have been to Spain, Italy, France, America, Mexico. I think that’s it… Oh, and the US.”

Due to geology, if Angie is to attempt the most difficult climbs she needs to challenge herself, she has to travel overseas. At the moment the rocks in Australia are generally too “reachy” for her height – the bits that you can hang on to are too far apart – and so off she goes to rock-climbing meccas around the world that allow her to compete against the world’s best.

Australia’s best female climber is former elite gymnast Monique Forestier. She is the only Australian woman to successfully complete a grade 34 climb. What’s it like having a 12-year-old nipping at your heels, I ask. “I am 44,” she says. “It’s about time there was a changing of the guard. Angie has got all those years of experience behind her and as she gets taller and stronger who knows what is possible for her.”

Forestier has watched Angie develop over the past few years and has been impressed by her ability to maintain the focus required to be an elite athlete. “There are a lot of young climbers who are capable and talented, but she does have the capability to translate that to performance on rock,” says Forestier. However, she is wary of placing undue expectations on the young climber. “She has already proven herself to be a great climber. We don’t need to push her to achieve more. She does that all by herself.”

In a climb there are points called cruxes; the really difficult parts where climbers will have to contort their bodies to make it to the next point. A climb is defined by how many cruxes it has and their difficulty. One of Australia’s best male climbers, Blue Mountains physiotherapist Lee Cossey, says the determining factor of grading a particular rock face is how many people can climb it. Only six Australians, five men and Monique Forestier, have climbed a grade 34, while 23-year-old Blackheath climber Tom O’Halloran is the only Australian to crack a grade 35. “Angie has an incredibly strong personality,” says Cossey. “She is very independent and incredibly self-motivated.”

But is it too much for a 12-year-old? “We do go through a lot of soul-searching and we do think, ‘Is it too much?’” says Claudia. “Angie is our youngest daughter. We don’t have any more kids, so in a way it is selfish. We are spending all this time with her and we really enjoy doing it. We get to travel the world with her and experience this as a family and so in that way it is about us.” Her husband Tek cuts in: “We are not spending our money on rubbish any more. The way we used to live was buying new things, like PlayStations for the kids. We now place less value on material things and more value on spending time with the family.”

What about those two insanely difficult climbs Angie attempted over the Easter holidays? She lucked out on Pure Imagination. “There was a bees’ nest and every time I was climbing they would come and attack me and I got stung. I couldn’t really do that one because they would always attack me near the hard part,” Angie says.

That left Lucifer – a sandstone rock face about 25m high on an overhanging cliff. There are three main cruxes on the climb, with no real rest points in between. For 15 of the 25 vertical metres, the climber has to pull their entire bodyweight up using holds the width of a fingernail. Imagine doing chin-up after chin-up on your fingertips.

And then there were the elements. It was heating up and very hot weather was predicted for the following days. She had one day to nail it. “It was obviously harder than any climb I’d ever done,” Angie tells me. “There are less rests and the holds are way worse. It was mentally harder because I was taking longer than I expected and it started to freak me out a bit and every time I would fall I would get really angry and upset because I was running out of time. We were running out of good weather; it was getting really hot.

“So by the end of it I was like, ‘I don’t care what happens, I’ll just give it a go’.” She fell off the top of the climb, three times, at a spot where she normally wouldn’t. “I was starting to give up.” And then, everything fell into place. She found her rhythm and in one 10-minute climb, everything held. She’d made an ascent.

“There were heaps of people there and everyone was very happy for me,” she says. “They were cheering me on and congratulating me. I didn’t think about it being the best climb by an Australian. I was just happy for myself. I felt pretty amazing.”

That night they celebrated. “We came back to the camp and we ate pizza, and we had a fire and lots of ice creams and I played with my two friends who are here, Gracie and Sara.” And what about Dogo? Her persistence paid off there too and she found him a good family. Dogo has achieved the great American dream – he’s moving to Canada. And Angie Scarth-Johnson is Australia’s best female climber, equal with Monique Forestier and two grades off the world’s best. She’ll turn 13 on May 20.

Climbing, for the first time, will be included at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics and Angie hasn’t decided if she will go for it – she prefers outdoor climbing to indoor and the format for the games may not suit her style. She would be just 16 – the age limit introduced for gymnastics in the wake of Nadia Comaneci’s success and the concerns it raised for physical harm to young athletes.

For the moment, Angie says, she just wants to nail a few more 33 and 34 grade climbs before becoming the first Australian woman to climb a grade 35. Time is on her side.