Ruthless, flamboyant businessman Mohammed al-Fayed couldn’t buy what he wanted most

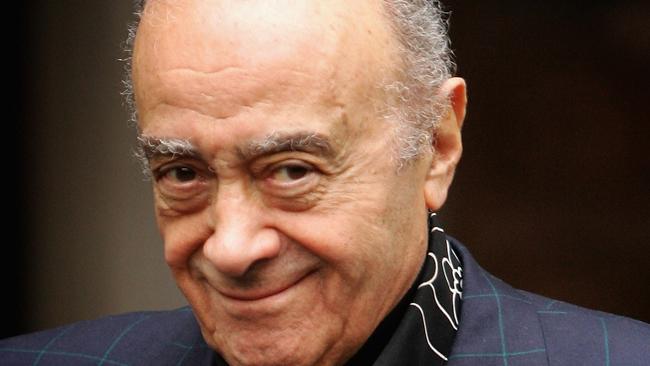

Ebullient but paranoid Harrods owner Mohammed al-Fayed turned on the royal family after the death of his son and Princess Diana and never achieved his most important goal.

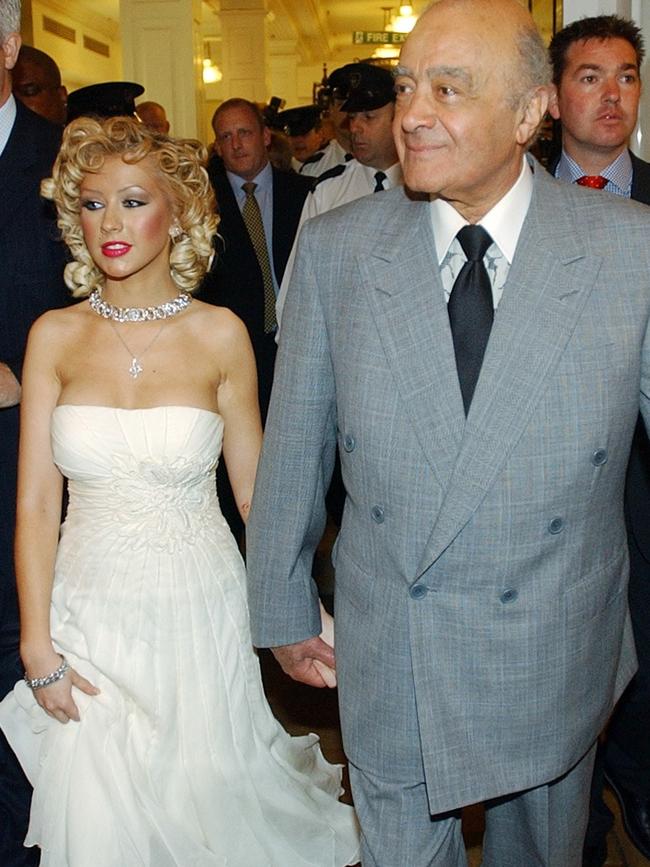

“Christmas has come early,” said a triumphant Mohamed Al Fayed in his strong Egyptian accent, posing with Father Christmas for pictures before surprised shoppers in his Harrods flagship store in London. He was celebrating victory in a 1999 libel case brought by the former Conservative minister Neil Hamilton, to clear his name in the “cash for questions” House of Commons scandal.

In the witness box, the ebullient businessman told Desmond Browne, representing Hamilton: “You talk absolute rubbish”, “It’s none of your bloody business” and much more. The trial, however, exposed Al Fayed’s journey from an Alexandria slum to great wealth, and the mental toll of his pursuit of fame, fortune and social acceptance.

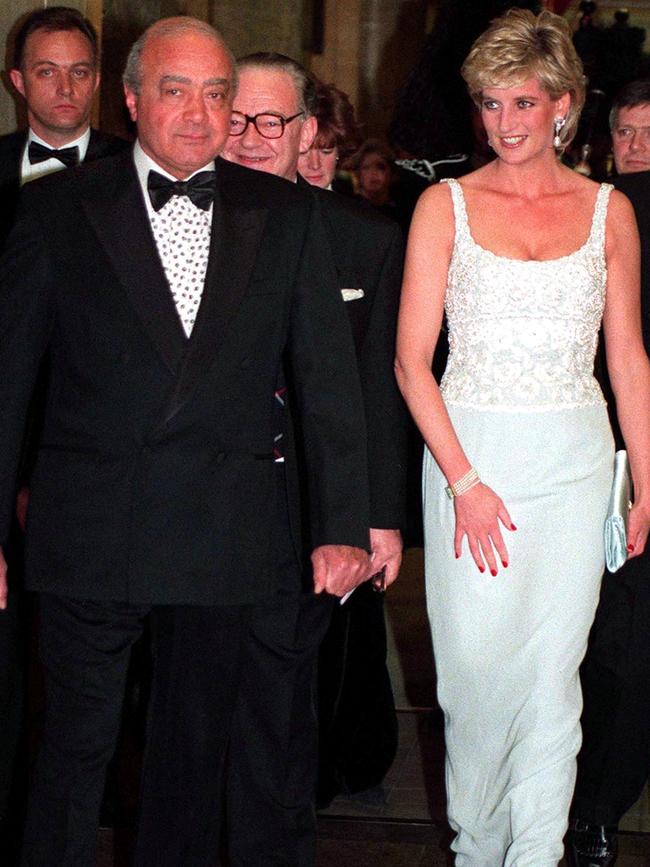

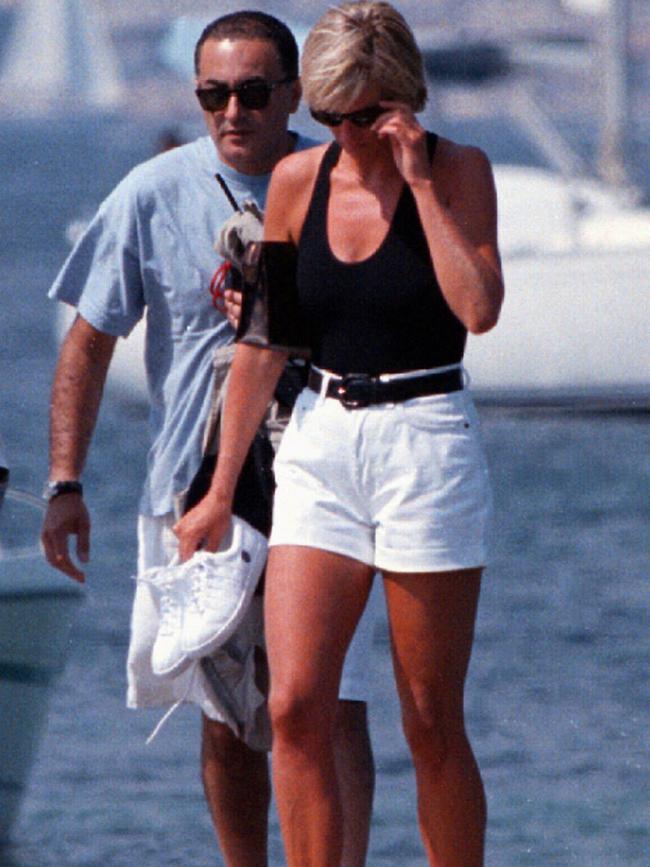

Al Fayed had harboured dreams that his playboy son Dodi would marry Diana, Princess of Wales, who had holidays on the family yacht with her sons, and alone with Dodi.

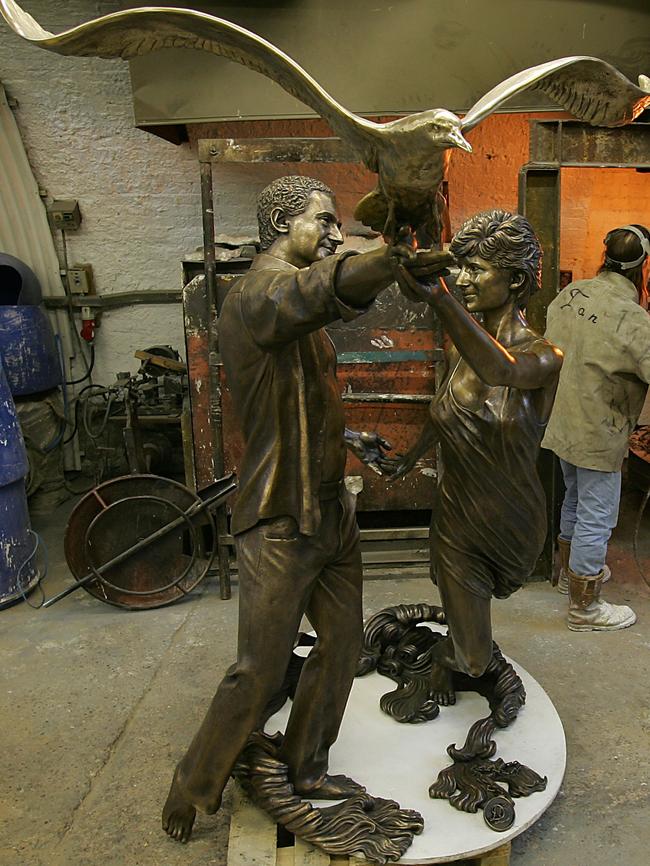

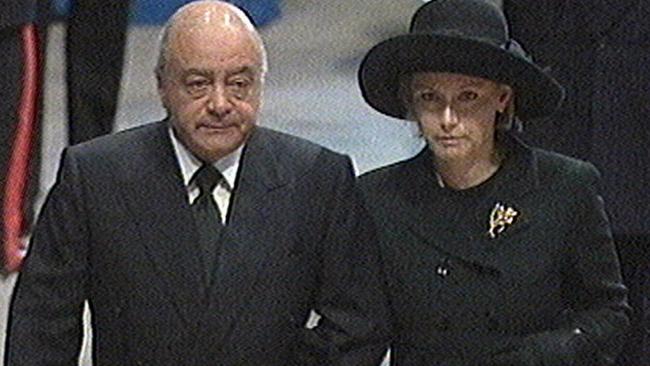

Al Fayed had played a big part in bringing them together but his dream of a passport to the heart of the British establishment died in August 1997 after Diana and Dodi were killed when the car they were travelling in crashed in Paris. Until then, Al Fayed appeared seriously to believe that his grandest social ambitions were about to be fulfilled, that he was to become a British citizen and father-in-law of Diana – mother of a future king.

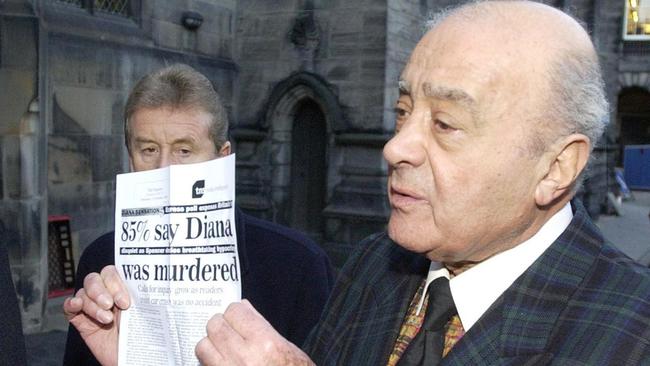

His reaction to the fatal crash was to deny all responsibility on the part of his drunken chauffeur in driving the couple to their deaths and instead to explain the disaster with outlandish conspiracy theories that led to the withdrawal of Harrods’ royal warrant. At the Hamilton libel trial Al Fayed accused the Duke of Edinburgh of masterminding the “murder” of Diana and Dodi, adding that he was “a murdering Hun with Nazi tendencies”.

Before the death of his son and Princess Diana, Al Fayed had established himself as a secretive businessman who gloried in what he regarded as the right kind of publicity to achieve his aims. A foul-mouthed, misogynistic street bully when he wanted to be, he was also capable of extraordinary generosity, especially to children.

Like other foreign entrepreneurs who emerged in Britain after the Second World War, he attempted to take on the persona and trappings of the classic English aristocrat: houses in the country and fashionable London, helicopters, private planes, the obligatory Rolls- Royce, expensive suits and appearances at Wimbledon, Royal Ascot and the Royal Opera House, where he might rub shoulders with the upper classes – and, ultimately, the royal family. He sponsored the Royal Windsor Horse Show in order to be seen sitting next to the Queen, until the deal was apparently cancelled owing to Al Fayed’s propensity for crassness and lewd wisecracks during the events.

Al Fayed’s wealth from shipping, construction and property had been achieved with an acute eye for opportunities, and knowing how to make himself useful. He added Al to his name in 1974, to make him sound more important under Egyptian custom. As his wealth grew, so did his paranoia, and he was constantly protected by former members of the Royal Military Police, Parachute Regiment, Royal Marines or SAS. He would obsessively rub his hands with lemon juice after shaking hands and avoided food and drink if he did not know their source. The Park Lane block where he lived became a high-security fortress infested with hidden microphones and cameras, and local police were bribed to keep their distance.

By 1974 Al Fayed was doing well enough to be targeted by Tiny Rowland. Thus began a relationship that was to have far-reaching consequences for both men. Within a year Al Fayed joined the board of Rowland’s company, Lonrho, after acquiring a block of Lonrho shares in exchange for shares in Costain, the construction company. But even Al Fayed was sufficiently disgusted by the corrupt way Rowland ran Lonrho to resign after a few months.

In 1981 Lonrho was blocked by the Monopolies and Mergers Commission from buying House of Fraser, the department store chain that owned Rowland’s ultimate target, Harrods. It was soon coveted just as keenly by Al Fayed. When in 1984 Fraser shares were sliding, Rowland sold his 29 per cent stake in Fraser to Al Fayed, on the assumption that he would buy the shares back and launch another bid for Harrods. Yet Al Fayed was secretly planning his own swoop on the department store.

Rowland was furious the following year when Al Fayed took over Fraser for £615 million. He had not reckoned on his rival borrowing the money, using Fraser’s assets as collateral. The entirely legitimate but unwitting lender was the Sultan of Brunei, who had given Al Fayed control over several hundred million pounds in relation to an entirely unconnected deal. Al Fayed may have broken his word to Rowland, but he had done nothing illegal. That did not stop Rowland calling for a government inquiry into the affair, which reported in 1989.

That report was sufficiently scathing to scupper Al Fayed’s request for British citizenship. So Al Fayed hired a lobbyist to pay Conservative MPs to ask parliamentary questions on his behalf, a breach of House of Commons rules. Angry that they did not do enough for the bribes, he publicly accused two of them, Hamilton and Tim Smith, of taking cash-stuffed envelopes. In what became known as the “cash for questions” scandal, the pair left parliament in disgrace. For good measure Al Fayed denounced another minister, Jonathan Aitken, for staying free at the Ritz Hotel in Paris, which Al Fayed had bought for £ 9 million in 1979. Aitken insisted he had paid for his stay there and was later was jailed for perjury.

In 1994 Al Fayed refloated Fraser on the stock market, minus Harrods, which he kept for himself. The sultan got his money back.

Having seen Rowland wage a campaign against him through his ownership of The Observer, Al Fayed tried to emulate his enemy. Attempts to buy several newspapers, including the Daily Express, were rebuffed so in 1996 he settled for relaunching the venerable humour magazine Punch and buying Viva radio. Neither lasted.

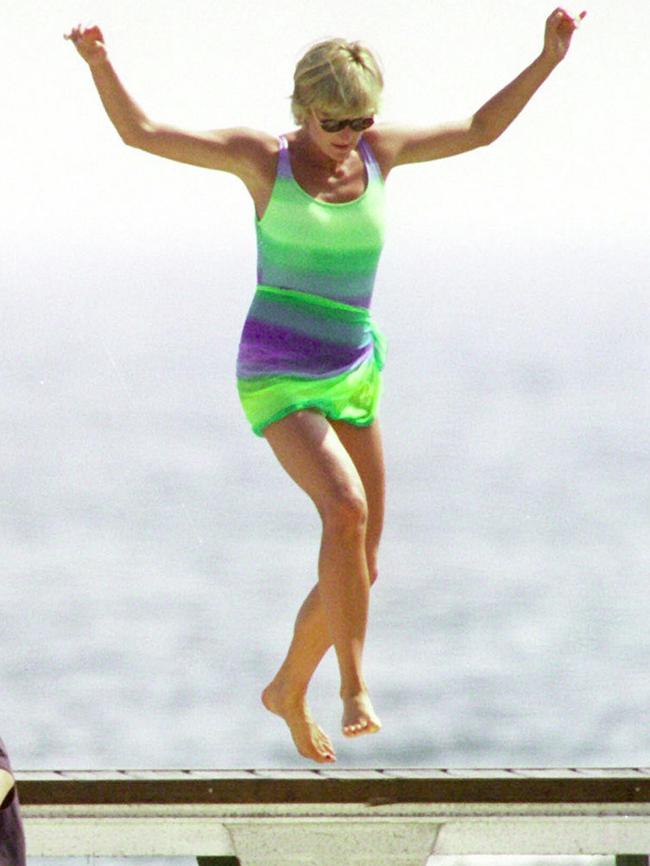

In his search for access to royalty, for several years Al Fayed had been courting Princess Diana whenever she visited Harrods. In the summer of 1997 she accepted an invitation for a family holiday on board Al Fayed’s yacht Jonikal, with the young princes William and Harry, then aged 15 and 12. “I’m like a father to Diana,” he said. She called it “the best holiday of my life”.

In August Diana agreed to a second holiday on board the yacht, this time alone with Dodi. She tipped off British national newspapers so that they could arrange to take photographs that she subsequently denounced as intrusive. Al Fayed told The New York Times: “It’s nothing really very special. She’s a free woman. My son is free. Normal people fall in love.” Then came the crash, killing Diana and Dodi. Sympathy for Al Fayed over the loss of his son evaporated after his claims of murder.

According to his Who’s Who entry, Mohamed Abdel Moneim Al Fayed was born in Alexandria in January 1933, although the 1989 UK government report said he was born four years earlier. He claimed that he came from a family of wealthy Alexandrian shipping and cotton barons who hobnobbed with sultans at the Paris Ritz. In truth his father, Ali Ali Fayed, was an impoverished primary school inspector. His mother was said to have died when Mohamed was four. Mohamed and his two younger brothers, Salah and Ali, and sisters, Sooad and Safia, were brought up in the El Gomrok quarter of Alexandria, near the port.

After leaving secondary school, Al Fayed worked door to door selling first Coca-Cola then sewing machines. His first important break was meeting Adnan Khashoggi, a friend of a friend, who had just left college. Khashoggi’s father was the personal doctor of King Abdul Aziz Al Saud of Saudi Arabia and became the country’s secretary- general of public health.

Hard-working and extrovert, Al Fayed talked his way into Khashoggi’s first business venture, importing furniture into Saudi Arabia. The wealthy Khashoggi family embraced him. Two years later, in 1954, he married Khashoggi’s younger sister, Samira, a union that produced a son, Dodi. They divorced in 1956, and Samira died in 1986.

His connection with the Khashoggi family ended acrimoniously. However he was presented with another opportunity after Gamal Abdel Nasser seized power in Egypt and nationalised the Suez Canal in 1956. Many foreign companies quit while shipping costs soared. Al Fayed bought these businesses and their owners’ property, charged fat fees to defeat Nasser’s harsh currency controls, and raked off lush shipbroking commissions. Visits to Europe opened Al Fayed’s eyes further to the riches within his grasp.

In 1964 a ship-broker friend tipped him off that “Papa Doc” Duvalier, the president of Haiti, wanted to attract foreign investment. Al Fayed passed himself off as Sheikh Mohamed Fayed, a rich Kuwaiti shipowner. In the belief that Haiti had large oil reserves, he offered to build a refinery and redevelop the dilapidated Port-au-Prince harbour. Al Fayed persuaded Duvalier to grant him a Haitian diplomatic passport, which would make it easier to escape many restrictions on Egyptians in Egypt. The oil reserves turned out to be a myth and after refusing to pay the huge bribes demanded by Duvalier, Al Fayed fled to London with the funds received for the harbour redevelopment. In 1965 Duvalier announced he was seeking Al Fayed “dead or alive”.

Al Fayed rented a flat on Park Lane, backing on to the Dorchester Hotel, and led a swinging bachelor life with fast cars, extravagant parties and glamorous girls. His next big break was meeting Mahdi al-Tajir, an adviser to Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed al-Maktoum, Dubai’s ruler. The small gulf state wanted a port and trade centre, but had no credibility with western banks. Al Fayed found the finance and took a commission on Costain, the UK construction company, doing the work. His share was £ 2 million.

From that point, Al Fayed invested in London property, including the whole of the block that contained his original flat. To that he added a fortified home in Surrey, complete with gilded statues of naked women in the garden, villas in Gstaad in the Swiss Alps and in St Tropez, the mansion formerly owned by the Duke and Duchess of Windsor in the Bois de Boulogne, and Balnagown Castle in Scotland, which he expanded from 12 acres to 65,000. In 1997 he added to his empire by buying Fulham Football Club, then in the third tier of English football. He invested heavily and four years later the club were promoted to the Premier League.

In 1985 Al Fayed married the 30-year-old Finnish socialite and former model Heini Wathen, to whom he had been introduced by Dodi in 1977. They had four children: Jasmine, a fashion designer, Karim, a photographer, Camilla, a charity campaigner and restaurant owner, and Omar, an environmentalist and publisher.

Heini was frequently humiliated by reports of Al Fayed’s treatment of women. He was alleged to have regularly used his power as Harrods owner to target young employees. A 17-year-old claimed Al Fayed told her: “I need you around me all the time. If you don’t sleep with me, I can’t help you with your acting career.”

In March 1999 Al Fayed was forced to admit knowing that his staff had broken into a Harrods safe deposit box rented by Rowland, who had died the previous year. He had to pay Rowland’s widow £ 2 million. Later that year the home secretary, Jack Straw, rejected Al Fayed’s third application for British citizenship.

As Al Fayed accepted that he would never achieve his social ambitions in the UK, he retreated from public life. In 2010 he sold Harrods to Qatar Holdings, the sovereign wealth fund of the Gulf state, for £ 1.5 billion. He sold Fulham FC in 2013.

He was a large donor to charity, mainly through the Al Fayed Charitable Foundation to help children in poverty and with life-limiting illnesses in the UK, Thailand and Mongolia. It has contributed millions to London’s Great Ormond Street Hospital, ChildLine and the Francis House Children’s Hospice in Manchester. In 1998 he bought West Heath girls’ school in Kent, where Princess Diana had been a pupil, and turned it into a school for children with mental health problems and special needs.

Although his health declined in later years, Al Fayed never lost his willingness to have a go at his critics. In 2011 he unveiled a statue of the late entertainer Michael Jackson outside Fulham’s ground, on the somewhat spurious justification that Jackson had attended a solitary game there. To widespread mockery, he replied: “If some stupid fans don’t understand and appreciate such a gift this guy gave to the world, they can go to hell.”

(Mohamed Al Fayed, businessman, was born on January 27, 1929. He died on August 30, 2023, aged 94)

The Times