Rules for flying: less travel, and economy here to stay

Every step of the air travel journey is undergoing seismic change to prevent the spread of COVID-19 and restore confidence.

In an uncertain time for the aviation industry, one thing is clear — travelling by air will never be the same.

Just as the 9/11 terrorist attacks of 2001 forced a global rethink of aviation security, this year’s COVID-19 pandemic has triggered its own wave of changes centred on public hygiene.

With human contact now considered the biggest threat to health due to the risk of viral transmission, airlines and airports are racing to tackle as many potential threats as they can.

Here to stay are stickers on floors mapping out how far apart people should stand. The same goes for clear hygiene screens shielding customer service agents and it’s unlikely hand sanitiser dispensers will ever be removed from airport entrances and boarding gates.

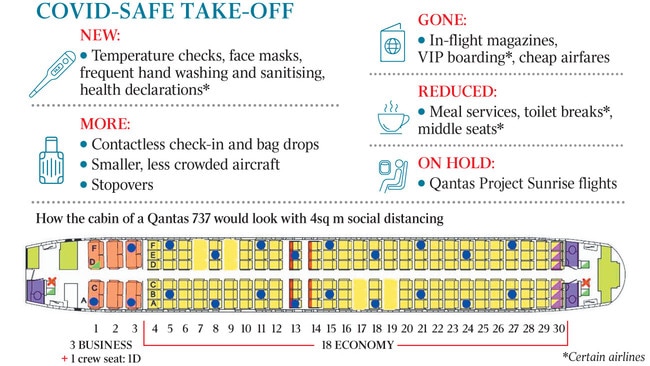

Less likely is any permanent removal of the middle seat to create more space between passengers but there are plenty of other measures being implemented by airlines.

Every step of the air travel journey is undergoing seismic change to prevent the spread of COVID-19 and restore confidence in an industry slammed by the pandemic.

Pre-flight

Simply booking a flight will not be the same, with fewer services going to fewer destinations in the next 12 months at least.

Qantas has already postponed its ambitious Project Sunrise flights that were set to carry passengers non-stop from cities on Australia’s east coast to places such as New York, London and Paris.

The timing of resumption of regular international flights is still unclear, although Qantas chief executive Alan Joyce hopes to have 40-50 per cent of domestic capacity back in operation by July.

Passengers should expect more “stopovers” on flights as airlines opt for triangulated services to reduce costs and maintain viability, flying from Brisbane to Perth via Melbourne, for example.

Flight bookings may also be a different process, with questions about the passenger’s health and recent travel, and information about the provisions made to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

The other big difference is likely to be airfares, with airlines facing bigger bills to upgrade hygiene standards.

Joyce has made it clear Qantas will be seeking to reinvigorate domestic travel with cheaper fares and he has warned that any push to enforce social distancing on flights could undo that.

“If we take the middle seat out, airfares will probably go up by around 50 per cent, and to go to 1.5m (between passengers) on an aircraft would mean you’d only have 22 people on a Boeing 737. That means airfares would be eight or nine times more than they are today,” Joyce says.

Anything in the preflight process that can be done without human contact will be, with digital boarding passes and electronic bag tags the “new normal”.

People may need permission to fly, particularly those who have recovered from COVID-19.

At the airport

As discussions continue between airlines and airports about extra health measures, many gateways have taken matters into their own hands.

Sanitiser dispensers are positioned at entrances, before and after security, and in shops and boarding gates, and signage encourages regular handwashing.

Stickers on terminal floors indicate how far apart people should stand, and bathrooms are kept scrupulously clean, surely one of the greatest side-effects of the pandemic.

Qantas is pushing for temperature checks to be carried out as people arrive at airports and Canberra Airport has already introduced thermal imaging at its security checkpoints.

Canberra Airport chief executive Stephen Byron says that to date only a handful of people have been detected as having elevated temperatures.

“It picked up a construction worker and it also picked up some people with beanies on,” says Byron. “When they’re picked up they go for a secondary screening with a nurse. When people remove their beanies or settle themselves, we’ve found their temperature comes down.”

JetBlue Airways chief executive Robin Hayes says it will become socially unacceptable for someone unwell to board an aeroplane.

“Airlines have to figure out how they’re going to respond to that in a way that still allows them to be profitable, but also recognise that you don’t want people on the aeroplane that are ill,” says Hayes.

From June 1, Regional Express Airlines will demand that all of its passengers wear face masks unless they have a valid reason not to, with anyone checking in without a mask forced to buy one for $2.

Qantas is more relaxed about masks, recognising it’s very difficult to inflict them on young children and people with respiratory conditions.

But Joyce says anyone arriving at a Qantas terminal who displays signs of illness such as coughing and sneezing will not be allowed to board aircraft.

“Our check-in staff and our crew will be on the lookout for people with symptoms and we will turn them away,” he says. “We’re giving people complete flexibility on their tickets so if they’re not feeling well on the day of their flight there’s no cost to changing their ticket.”

As part of the planned return to more regular flying, Qantas will be staging a staggered opening of its altered airport lounges.

Layouts are likely to be different, with much more distance between seats, and limits will be imposed on the number of guests inside the lounge or Qantas Club at any one time. Buffet-style dining and self-serve drinks may well disappear, along with communal reading material.

In the air

Instead of magazines and newspapers, passengers will be offered face masks and antibacterial wipes on Qantas flights for their travelling comfort and that of others.

Neither will be mandatory, with passengers “encouraged” to wear face masks for the comfort of others, and given the option to re-wipe their seats and tray tables for peace of mind.

Food and beverage services will be minimised to reduce contact between crew and passengers, and movement around the cabin discouraged.

In the case of Irish low-cost carrier Ryanair, passengers wanting to use the bathroom are being asked to raise their hand to request permission from cabin crew, instead of standing in the aisle.

US carriers Delta Airlines and Southwest Airlines have committed to some social distancing on flights, accepting bookings for only 60 per cent of seats.

The concept of blocking out middle seats to ensure more space between passengers is a sensitive one, with the International Air Transport Association leading calls for airlines to be exempt from such rules.

Indeed, Qantas is adamant there is no medical basis for that due to the hospital-grade air filters on aircraft that remove 99.9 per cent of bacteria and viruses from the cabin. It’s a point Joyce has been at pains to make since the pandemic began, highlighting at every opportunity the fact that an aircraft cabin is much different to other enclosed public spaces such as buses, trains and restaurants.

“The filtration, the way the cabin is set up, everybody’s facing in the same direction and the air flow is from top to bottom,” Joyce says. “We’ve carried a lot of people around the world since COVID-19 has come out and there’s been no known person-to-person transmission on an aircraft.”

It’s a view backed by Australia’s Deputy Chief Medical Officer Paul Kelly, who says it’s safer to fly on a plane with potentially hundreds of people than to sit inside a cafe with fewer than 10.

“I would say that on aircraft there are very specific engineering things that happen in relation to the ventilation on aircraft and so forth which can make it safer than a closed room, for example,” Kelly says. He says airlines, like all industries, needed to do their own risk assessments.

Turnaround times between flights could be longer in the post-pandemic world due to more intensive cleaning of seats, tray tables and belts, as well as bathrooms and windows.

To that end, Boeing is looking at the use of ultraviolet “wands” for cabin crew to use after passengers have disembarked, to more efficiently clean surfaces and kill any viruses. The aircraft manufacturer has also flagged a special coating of surfaces that would instantly kill germs on contact.

Alternatives

Given Australians’ reliance on air travel, it’s hard to imagine any long-term resistance to flying within the country. With marathon road or train trips the only alternatives, flight bookings are expected to steadily ramp up as state borders reopen. According to Joyce, 98 per cent of Qantas’s 13 million frequent flyers are already planning their next trip.

But Brisbane-based charter operator Alliance Airlines is convinced many large businesses will continue to use charter flights, after resorting to those typically more expensive services during the pandemic.

The airline has seen a strong upsurge in demand for charters, driven by a desire for social distancing on planes and a lack of availability of scheduled flights.

“Those sort of changes are likely to be permanent or around for a very long time,” says Alliance managing director Scott McMillan.

“Once people get a taste of being able to fly where they want, at a time that they want, they won’t want to go back.”

Limited commercial services will also favour charter operations, he said.

“Take Emerald (in central Queensland). There used to be five regular public transport flights a day to Emerald now there’s two a week,” McMillan says.

“We are years away from seeing that again.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout