Musical set in the bitchy world of fashion? It’s groundbreaking

As The Devil Wears Prada hits London’s West End, the fashion editor of The Times (and former Vogue assistant) reveals the reality of life at a glossy magazine.

The Devil Wears Prada was released in cinemas in 2006, the year I graduated and began looking for internships at women’s magazines – and it did nothing to put me off. I remember reading the original book while sitting on a bench outside Vogue’s London office, having arrived 40 minutes early for my interview (just to be on the safe side), and hoping that I too might one day be as fabulously downtrodden as Miranda Priestly’s new assistant, Andy.

When Lauren Weisberger’s dogsbody’s eye view (loosely) fictionalised the offices of American Vogue in 2003 it made Anna Wintour a celebrity far beyond fashion and media circles. Now The Devil Wears Prada and its legendary editor-in-chief, Miranda Priestly, have been turned into a West End musical, with a score written by Elton John, who calls it one of his favourite films.

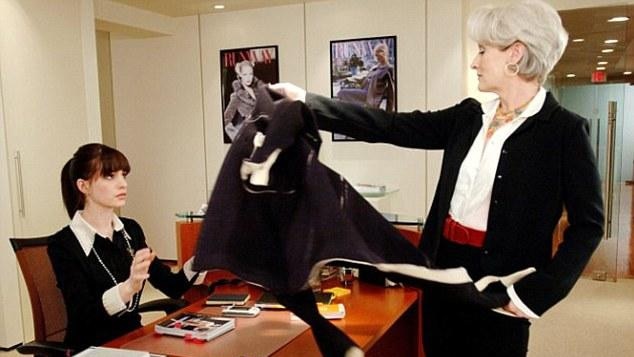

Back then, of course, I identified as Andy, played by Anne Hathaway in the film, as I went in hoping to write features and instead found myself folding designer clothes borrowed for fashion shoots, fetching coffees and, at another publication, looking after the small children of an editor you have probably heard of. It was a man, before you reach for the “ice queen” stereotype.

This was just the way you got a job at these places if, like me, you were not fabulous enough to have your name passed straight to HR by a hereditary peer. Not with zeitgeisty ideas but by proving yourself unflappable and emollient to the point of servility. After four months of folding and fetching, I got my first job as an assistant at another Conde Nast title, Glamour – then the best-selling women’s glossy in Europe – where I added packing suitcases to my CV. For shoots, that is, not divas.

Budgets have shrunk since then, and so have egos. Pre-crash we flew to New York once a month to shoot with photographers based there; the high-ups received free iPads from beauty brands, and (some) editors still threw shoes at people who annoyed them. Miranda’s acerbic senior assistant, Emily, played in the film by Emily Blunt, remains recognisably A Type in fashion, witty and hungry in all senses of the word (although she’d probably be on Ozempic by now, so will the diet jokes need rewriting soon?), but these days she’d know not to be mean to anyone’s face in case she was cancelled.

Many of the industry’s more flamboyant characters – such as the lobster-hatted Isabella Blow and Wintour’s caped commandant, Andre Leon Talley – have departed the scene too. It is the influencers who peacock now while fashion editors look on in navy jumpers, as scandalised as Maggie Smith’s dowager duchess. Presumably, if faced with TikTok, Miranda would take the view – as Wintour seems to – that you join, rather than beat, the forces of change. This is the substance of a film sequel said to be in the works.

Vogue has evolved since I returned as a freelancer one summer 10 years ago, when the internet was still seen as a blip. After the busy newspaper and digital start-up offices I’d worked at, the hallowed desks of Hanover Square had an almost library-like hush. That wasn’t because everyone was terrified – they were just quietly diligent. A lot of them were also out at breakfast until almost midday.

The only thing that might shatter the peace was the arrival of a really good outfit. Previously, I had worked at a left-leaning newspaper full of middle-aged men in zip-off walking trousers. Vogue was like commuting to a butterfly house by comparison – you could see them massing: the rich person hair, the handbags, the je ne sais quoi. When people got it right they were unofficially awarded the sort of welcome your average red-carpet attendees can expect: What are you wearing? Who is it by? What’s that handbag? How much was it?

Just joking: nobody talked explicitly about money, but they did love a bargain. One such “great deal” was on a juice cleanse – only £100 ($192) a day for five bottles. Another was a sample sale, at which designers sell pieces for often a tenth of the price, which still makes most things at least £200. I once found myself on the way to one with two colleagues I later found out were gajillionaires before realising that, as a jobbing freelance with no fixed salary, I should probably peel off. Thank God I did: they came back with several carrier bags apiece, Pretty Woman-style.

As the fashion editor at The Times I am regularly asked whether life as one is anything like The Devil Wears Prada, so I have a standard response: “Not at newspapers, less at magazines than it used to be.” I will now add: “And not at all like the musical.” In the years since the film came out several of Meryl Streep’s zingers as Priestly have become the stuff of memes, from her withering response to an unimaginative idea (“Florals? For spring? Groundbreaking”) to the “cerulean monologue” tongue-lashing she gives Andy for not taking Runway magazine seriously enough. My favourite is her search for “a slender female paratrooper” to feature in an article (“Am I reaching for the stars here?”) and the splendidly singsong passive-aggressive “why is no one ready?” to a room full of people moving as fast as they possibly can.

Yet where the front row looks on the film with something close to affection, the musical might have to work harder. That’s because the cult that has sprung up around this tale of stilettos at dawn is now about as far removed from the industry it depicts as, well, anybody still wearing stilettos. When a character used the word “fashionista”, I struggled: it has been unofficially banned by anybody who might pass for one since about 2007.

The Devil Wears Prada is of an era before the word “basic” became an insult, a time when men were men and women were glamorous. That glamour could be easily measured – per the retro clip of US Vogue’s ’90s It-girl Plum Sykes that has gone viral on TikTok recently – by “who would wear a chiffon Dolce & Gabbana skirt to the office?” and who had the highest heels. (Sykes is said to have inspired Emily in the film, who in 2024 parlance has the “main character energy” Hathaway’s Andy so lacks.)

Twenty years on, social media and countless documentaries – such as The September Issue and Disney’s recent In Vogue – have opened up the exclusive world of high fashion to such an extent that the musical’s rather lacquered look now feels a little passe, in a way the film did not. Perhaps that’s unavoidable in kitschy theatreland, where the only people wearing head-to-toe black work backstage rather than on the front row.

Weisberger famously described Vogue’s staffers as “the clackers” for the sound their heels made as they walked; I suppose there isn’t much onomatopoeia to the Alaia ballet flats and The Row loafers they are wearing today. Instead, the chorus of tastemaker magazine mavens who strike such fear into dowdy Andy’s heart are dressed like air stewardesses, while she looks more Prada before her makeover. Afterwards she resembles Ricki Lake.

I know, I know: I’m a bitchy fashion editor with a few esoteric quibbles, but where Weisberger’s book felt like an insider’s account of a cloistered world, the musical is like watching Dancing With the Stars. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, but Vogue it ain’t.

Sure, there were a few moments of scratchiness when I worked there, but it was a pretty normal place once you adjusted to everybody referring to clothes and handbags with female pronouns. The daily barrage of questions about your clothes felt genuinely enthusiastic, rather than a Mean Girls-style trap to fall into. Regina George, like Priestly, has also been rendered as a musical madam in recent years, but can a treasured, savage baddie ever be as affecting when they are singing and soft-shoe-shuffling?

Fashion people know the importance of gravitas – not to mention how easily it is lost – so they rarely dance, even at parties, unless you count a slow paso doble of the eyes across each shoulder and to the door while you’re speaking to them. Where Streep’s Priestly felt unnervingly icy yet human, Vanessa Williams (best known for playing another supercilious editor-in-chief in Ugly Betty) in the role is hot-tempered and has all the best tunes.

There is a lot in The Devil Wears Prada that still feels familiar too: money and snoot, diva demands and an endless, slightly nebulous hierarchy to scale, each station of it peopled with those treated so badly in their day that they feel duty-bound to inflict the same on whoever comes next. And it’s still a great yarn – that’s why I partly set my first novel, a thriller called The New Girl, in the jostling world of fashion magazines. But this behaviour feels increasingly retro, hammy even. When Wintour wouldn’t remove her shades for the Disney+ TV series recently, it felt almost like a calculatedly Priestlyesque move designed to bolster her legend (and its ratings).

I never experienced the US office of subzero repute – though a friend who worked there in the ’70s remembers finding Sigourney Weaver, then a model, crying in the lavatory after being told she was “too ugly”.

When I got my role at The Times, one of the Voguettes told me “people tend to get the job that suits them”. I think it was meant as a compliment, but it also sounded a lot like confirmation that, no, it wasn’t in my head that they all thought I was too fat and poor to move among them.

The stage show is a more inclusive affair. Once you accept that what you are watching is more Drag Race than cinema verite, you will enjoy yourself as heartily as I did. Allow your toes to unclench, maybe even pick up a “Florals? For spring?” T-shirt in the extensive merch shop by the foyer. It’s a glitzy evening that fans of the film will love and fashion types will delight in rolling their eyes at. As Miranda would say – that’s all.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout