Kids have bigger concerns than Covid, says author John Marsden

From ‘Madly Obsessive Older Mothers’ to the benefit of calling children fat, John Marsden has firm views on kids’ needs and toxic middle-class parenting. If that drives people wild, too bad.

Sunday, and the teachers at Candlebark school are working. Regional Victorians have just learnt they’ll join Melbourne in the state’s sixth lockdown, and the teachers gathered in the school’s kitchen are wrapping bundles of exercise books in butcher’s paper, popping a chocolate frog in each before sealing it with sticky tape. From here they’ll distribute the parcels via a network of parent helpers to the 170 children that travel from towns in the Macedon Ranges to this school like no other.

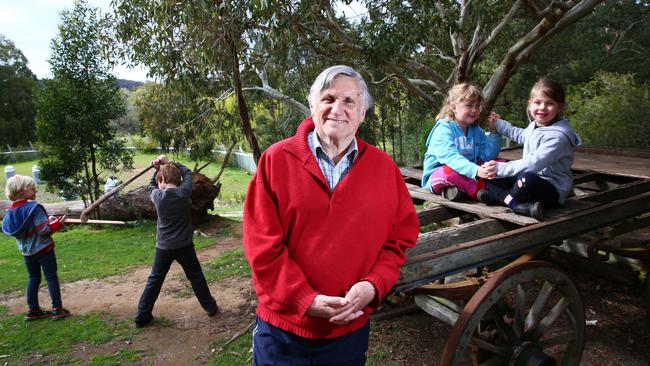

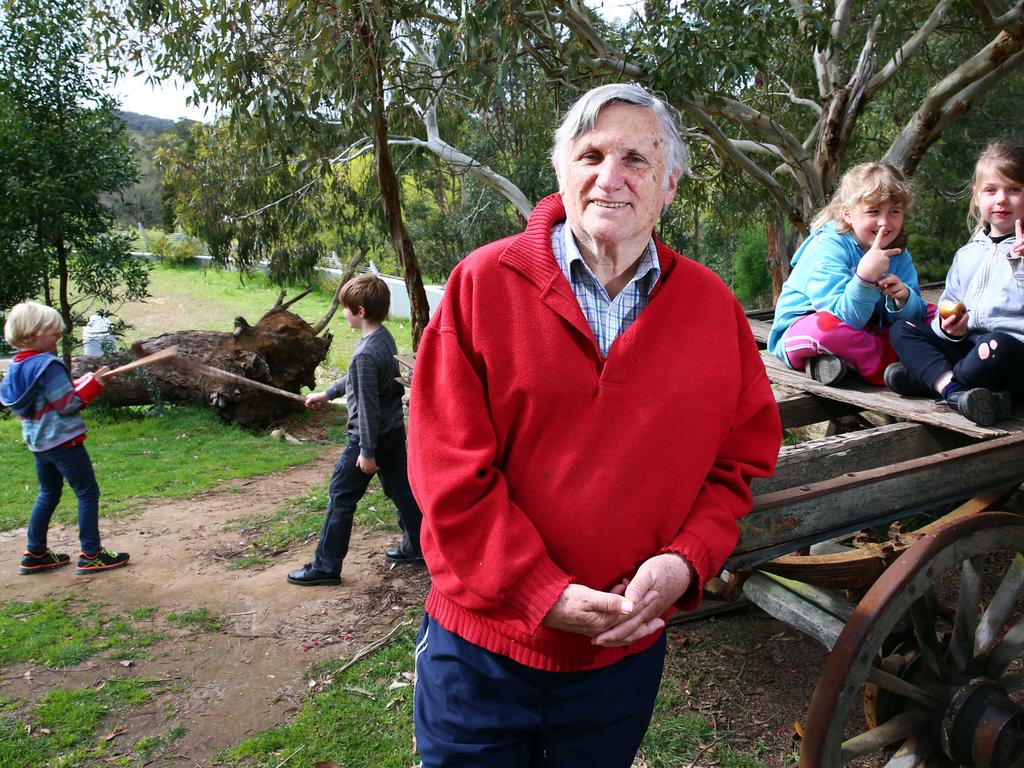

The alternative school, which takes students from Prep to Year 7, was opened in 2006 by Australia’s biggest name in young adult fiction, John Marsden. It sits on a steep hillside near Romsey, 60km north of Melbourne. Heavy curtains of stringybark enclose the 485ha rural block; inside there are grassy playgrounds and lopsided sports fields, trampolines and tree houses, chessboard tables with railway bench seats, vegie planter boxes, an open-sided shed with a jumble of pogo sticks, hula hoops, hockey sticks and skateboards. The library could be a modern-day home for hobbits, cocooned into the hillside and doubling as a bushfire shelter. There’s no staff room, no noticeboards, no signs with rules or buildings named after letters of the alphabet. It’s a place of peace and freedom and imagination; the inside of a storybook, perhaps the inside of a great author’s mind.

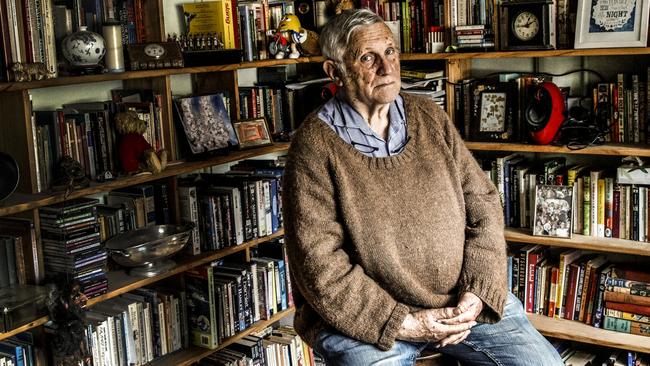

Marsden emerges from the principal’s office in faded jeans, an oversized brown knit jumper and battered black sneakers. He speaks and moves softly, without a hint of hubris, his most audacious feature startling blue eyes, set among a pale, sun-weathered face. Be wary of charisma, Marsden writes early in his new book. It’s often a symptom of narcissism. Candlebark is his place of grounding, and he drifts like a leaf, showing me round the gardens and classrooms. “I’ll go and do these fancy book tours and stay in nice hotels and get red carpet treatment, then come back here and resume looking for the sunhat of the kid who lost it on Friday, and whose parents are agitated because it cost $15. Then I feed the rosellas.”

Now aged 70, Marsden has written more than 40 books, sold more than five million copies worldwide and won every major award in Australia for young adult fiction. He’s most known for his 1993 novel Tomorrow, When the War Began, told from the perspective of a teenage girl caught up in a guerrilla war against foreign invaders.

But lately he has found himself mired in a new battleground, as he turns his pen on the real world. His 2019 book The Art of Growing Up was a no-holds-barred treatise on toxic parenting and the increasing emotional child abuse he sees emerging in middle-class families. Some critics panned the book as being needlessly combative, judgmental and contradictory, all anecdote and no evidence. One said Marsden seems intent on “alienating pretty much everyone”. The author was accused of everything from victim-blaming to being an apologist for domestic violence. Even his acclaimed early work from the seven-book Tomorrow series copped a modern-day whack, with a fellow novelist accusing him of perpetuating a xenophobic stereotype. Another said he’d let his young readers down by not empathising with bullied teenagers. I ask a literary critic, who shrugs: “He’s an old white guy with strong opinions.”

Suddenly it seemed one of Australia’s literary heroes was looking of another time, lost in the woods of wokedom, a dinosaur unwilling to bend to the new dictum that decrees the worst thing you can possibly do is offend someone. But none of this bothers Marsden in the slightest, nor has it tempered his uncompromising approach to telling the truths he believes we need to hear. His new book, Take Risks, picks off where The Art of Growing Up left off, in the very place we find ourselves on this sunny Sunday: the schoolyard.

“You know, I’ve lost fear of people’s opinions,” says Marsden, “and running schools has been a factor in that, because every day I’ll get lavishly praised and acidly criticised, so neither has much effect.” Marsden has visited more than 3000 schools in his life. He says he can judge a school almost instantly by observing the way the kids behave in the canteen line, whether people make eye contact as they pass, the vibe in the staffroom, the amount of litter on the ground, the general level of energy or apathy.

The book is named after the motto of Candlebark, where taking risks is not so much encouraged as mandated. There are no permission slips for excursions or camps here, nor at Alice Miller, the high school he opened in 2016 near the town of Macedon. Snowfall overnight on the summit of Mount Macedon? Jump in the bus, kids! Parents here don’t get the option of shielding their kids from the world, or making judgment calls on their safety. Academic rigour is high, but Marsden measures success by whether the kids graduate with empathy, wisdom, understanding, insight, and the skills to communicate with others and repair relationships.

Thanks to lockdown, during my visit the chatter of Candlebark children has been replaced by the cacophony of currawongs, sulphur-crested cockatoos, ravens, rosellas and rainbow lorikeets, screeching and scratching, drinking from the puddle under the table tennis table, pecking at the seed Marsden scatters each morning. It’s the choughs though that most fascinate him. “I could watch them all day,” he says. “They prefer to walk rather than fly. They form gangs and fight with other gangs. They come screaming in to protect one another. They’re bold and confident.”

It’s bold and confident kids that Marsden says he’s trying to nurture at his schools, and they’d want to be, because at times the world he paints in Take Risks hardly seems a place you’d want to raise a child. It’s a place of corrupt, self-serving politicians, teachers devoid of ideas, principals paralysed by inertia, parents so fearful of their children being injured that they shelter them from the world, inflicting emotional damage instead; a society populated with concrete thinkers and concrete playgrounds and a bureaucracy so rigid that it’s nearly impossible to change anything. Then there’s the small matter of the complete demise of civilisation.

“We now have evidence the size and weight of Jupiter,” he writes, “that humanity may not be capable of saving itself and its only known home, Planet Earth, from catastrophe.” The destruction of native forests, animal extinctions, plastic in the ocean, ice melt, the concentration of so much wealth among so few, the lack of help for developing nations – “we are clearly in a very perilous state”, Marsden says, as we take a stroll past the music room, a cabin built onto the back of an old Bedford truck. That could be one reason he appears not overly concerned about the impact of the pandemic or remote learning on students: they have bigger concerns. “Far greater is their anxiety about the world and the environment. I think that’s a much bigger and deeper and longer lasting fear, and it’s got them really shit-scared.”

But if you can look beyond the looming apocalypse, Marsden’s book is largely celebratory, or at least it should be. It follows his quite incredible personal journal from troubled kid to best-selling author to creator and principal of two successful schools (with about 400 students between them; at Candlebark admissions are full until 2024). He’s done what he wishes more people would do: identify a problem and bloody well fix it. He’s proud of what he’s created, and has every reason to be. But he looks tired. Tired of fighting the bureaucrats, tired of the ridiculous demands on schools, which he says are now expected to fill the void left by fragmented families and failed public institutions.

Marsden could (and nearly does) fill a chapter about the torrent of emails he receives every day from various departments and organisations suggesting or instructing that his schools teach every facet of life, from swimming to sexual consent. A proposal that schools teach kids to drive recently landed in the inbox of Alice Miller head of campus Sarita Ryan. “I mean, at what point does our responsibility end?” she asks. “It’s got to the point where schools are expected to be responsible and parents not.”

Dr Mandie Shean from Edith Cowan University’s School of Education is critical of many elements of Marsden’s approach, but agrees that schools have become overburdened with societal expectations. “Schools become the panacea for all of society’s ills, and also the cause. A healthy ecosystem is where schools reflect the wider message, rather than being responsible for instilling it.”

Marsden’s a big believer in the saying that it takes a village a raise a child. The problem is we’ve lost that village. “The extended family doesn’t exist like it used to, grandparents scattered across the country, families fragmented. People have smaller families and more leisure time than ever before, so parents are focusing too much attention on their children.” One of the biggest problems, he says, is parents thinking they own their children. “There will be many influences and forces that will help shape the child. If you try to be the only influence and only force you’re going to damage your child irredeemably.”

Marsden has a lot to say about parenting and is not afraid to say it, no matter how loudly he gets shouted down. “One of the great silences in Australia is that we don’t dare criticise parents or parenting,” he says. “Many people feel threatened by any conversation that might cause them to acknowledge they have weaknesses or have made mistakes. One thing parenting did to me was confront me with my own weaknesses and mistakes. It was f..king confronting and unpleasant, but I did eventually learn a lot about myself.”

John Marsden was born in Victoria in 1950, one of four children and the great, great, great nephew of the famous clergyman Rev Samuel Marsden. The family lived in Kyneton, Victoria, and Devonport, Tasmania, before moving Sydney when John was 10. He received a scholarship to attend The Kings School in Parramatta, a conservative, Anglican institution he describes as a threatening and dangerous place. The family home, though, was far worse.

Marsden says he’s never talked publicly – or even privately, except to a therapist – about the abuse he received as a child. “My father was a sensitive man who was very angry for much of his life. He would express that anger to his sons pretty forcibly. I learnt to keep my distance from him at a very early age.” His mother, he says, was typical of her generation in that motherhood wasn’t about showing love, it was about raising good citizens with a strong work ethic. “I don’t remember my mother touching me [with affection] at all. She cut our hair, probably put plasters on us if we got a scratch. But I don’t remember ever being hugged.”

Kindness from adults is something Marsden experienced so rarely that he remembers each occasion: featuring two teachers in grade four and six, a woman in the Devonport supermarket who would hand out soup samples, his grandmother who he saw once every couple of years, and the two women who worked in a hamburger shop in Parramatta, where he would often eat his dinner after school to avoid going home. He credits those people with saving his life.

At 18 he escaped his toxic home life, running away from home in the middle of the night. He now had independence, some control over his own destiny, but he couldn’t shake the traumas of childhood, and at 19, racked by suicidal thoughts, checked himself into a psychiatric hospital. “I was rational enough to think ‘the only thing I haven’t tried is to see a psychiatrist’. I thought I’d be stupid to kill myself without at least trying.”

In the following years Marsden took any job he could find, eventually settling on a career as a primary school teacher in his late 20s. A formative experience came when he was appointed head of English at Geelong Grammar’s prestigious Timbertop campus, in the mountains near Mansfield. At Timbertop Year 9 students lived away from home and took on physical and mental challenges in the outdoors. It reaffirmed for Marsden the value of giving young people experiences as a path to learning and growth. “I couldn’t believe what the students were doing at that place,” he says, “and the heights they reached, both metaphorically and literally. There were kids that had never left the city before, and they were having to hike up mountains for days and live in the bush.”

If Timbertop was an example of everything a school could be, returning to teach at Geelong Grammar’s Corio campus was a jolt back to Earth. Kids were going backwards, the same students who had been trusted to cross mountain ranges on their own no longer trusted to cross the street without a lollipop lady. The school was suffering from a “turgid administration, top-heavy with bureaucrats” and teachers “so institutionalised that they ceased to function as human beings”.

He credits a stint teaching at Fitzroy Community School, an alternative primary school in Melbourne’s inner north, with showing him how an independent school could do things differently and achieve great outcomes. The kids were relaxed but not unruly, and despite the bohemian appearance academic standards were exceedingly high. And the philosophy wasn’t up for negotiation; if the parents didn’t like it, they knew where the school gates were. It was a model Marsden would import almost wholesale to Candlebark.

In 2005 he found himself in a unique position. His annual income from his novels, speaking engagements and workshops was topping a million dollars. It allowed him to fulfil a dream and open his school, one for giving children the respect, love and opportunities he never had. He met his wife Kris Rielly, a single mum with six boys, in 2009, and they married two years later.

Marsden describes the well-publicised outrage over a few lines in The Art of Growing Up, where he suggests that what some call bullying could sometimes be better explained as children giving “feedback” on “unlikeable” behaviour – as a “predictably mindless reflex-response”. It’s certainly not left him gun-shy, writing in Take Risks that kids calling an overweight child “fatty” may be “the best they can do to convey the message that they think the child needs to lose weight”.

In a book full of breathtakingly fearless opinion and honest insight, you sometimes wonder if he is deliberately poking the bear. Surely if he wants to avoid a “reflex-response” he might think twice about introducing labels such as MOOMOO, or Madly Obsessive Older Mother of One. These women, he writes, “have only one child, and have had that child late in life. The mother is often overweight, and her life is likely to be unusually circumscribed… If they have husbands, these men are extraordinary in their passivity.” You can almost hear the knives being sharpened.

Other times he seems caught up in a new-age hypersensitivity towards literature that’s far beyond his control. In August 2018 Marsden appeared on the ABC chat show Q&A as part of a Melbourne Writers’ Festival special. During the episode Michael Mohammed Ahmad, author of The Lebs, said that in Tomorrow, When the War Began he saw a “paranoid, white nationalist fantasy about a group of coloured people illegally invading the country” and that it perpetuated xenophobia against Asians.

Marsden finds the remarks bizarre, not least because the nationality of the fictional invaders in his Tomorrow series is never revealed (although one might assume it would be an Asian country based on geography alone). He says he has great sympathy for the immigrants who suffered racism and bigotry, but that in trying to categorise one type of discrimination or abuse as worse than another you get into dangerous territory. “I was abused in awful ways as a child, the details of which people don’t know about. So for one group to say, ‘you’re pigs because you don’t understand what we’ve suffered’ is meaningless, because they don’t know what the other group has suffered. So yeah, I wanted to talk to him [Ahmad] afterwards and put that to him, but he wouldn’t have a bar of any conversation.”

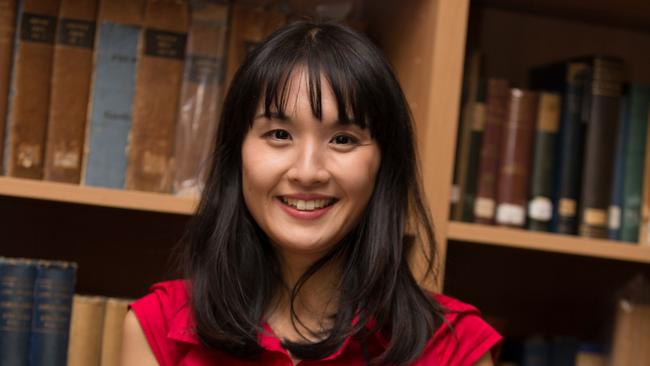

Melbourne writer Alice Pung, whose parents survived the killing fields of Cambodia to flee to Australia just before she was born, wrote an essay on Marsden in 2017 as part of an “authors on authors” series. She says she never saw the invaders in the Tomorrow series as being Asian. “The books really resonated with my friends and me, though, because we came from a war zone. I certainly don’t see it as racist at all.” Pung says Marsden’s great skill as a writer is the ability to get inside his characters and walk in their shoes. “He has an incredible level of insight… His books are timeless because he gets to the essence of what it means to be a young adult, that struggle between feeling powerless and having a sense of agency in your life. So I think we should listen to him when he talks about the real world, because that’s what all his books are about.”

Alice Miller school is named after a Polish- Swiss psychotherapist and author who once said: “I can imagine that someday we will regard our children not as creatures to manipulate or to change, but rather as messengers from a world we once deeply knew.”

“John is an absolute visionary,” says Sarita Ryan. “And he’s uncompromising in that vision. Some of his approaches are unpopular and not necessarily welcome by parents or people in the community. But he has absolute belief in the capacity of young people, and that drives him.”

She remembers the time a boy was playing barefoot in the garden and put a shovel into his foot. “It was bleeding and he was crying, so I took him to the first aid room and said to John, ‘That’s it, from now on everyone in the garden has to wear shoes’, and John just looked at me and said, ‘Never make a decision from the bedside of the injured child.’ That says a lot about John. He pushes back against the encroachment of limitations and rules, and things that impinge on freedom, even if it means you sometimes get hurt. Because so many decisions are made from that bedside.”

Claire Vannuccini says she enrolled her son Jaxon at Candlebark because it suits his high-energy, tactile nature. “He’s one of those kids that needs to run his energy out… he learns through all of his senses. I’ll sometimes ask Jaxon what he learnt at that school that day, and like a typical kid he’ll reply, ‘Nothing.’ So I’ll ask him what he did that day he’ll say they went for a walk in the bush and ‘did you know Mum that a bowerbird makes a nest by collecting shiny blue objects?’ and he’ll tell me all about the bowerbird.”

She says Jaxon is learning how to handle issues he might regard as bullying in a more self-reflective light. “He might come home and say to me ‘so and so was mean to me today and hit me’, and I’ll ask him to tell me the story. And then say to him, ‘So basically you were annoying him and he annoyed you back and you both hit each other, and now you’re best friends again, is that right?’ I’ll tell him that actions sometimes have repercussions, and you can’t predict what they’re going to be from some people. None of this is victim-blaming, it’s teaching people to reflect on their own behaviours.

“That school has really been a gift for us,” Vannuccini says. “I’ve watched my boy go from ‘I think I’m stupid, I think I’m dumb’ ever since kindergarten to this confident, courageous, thriving person. It’s all I want.”

In a Candlebark classroom there’s a cardboard castle where the children build little compartments for characters – in their own space, but part of the same community. Marsden picks up a princess that has fallen from a turret. “The kids are learning at Candlebark. They’re learning about relationships and communication and how to manage conflicts and how to find strategies that might work in solving a problem. It’s a different way of learning, but the learning is more profound and far more lasting.”

I ask if he ever repaired his relationship with his parents. “In a way. Running away was a decisive act, because it meant that I wasn’t controlled by them. Forgiveness is a meaningless word, because if someone chopped off your hand you can forgive them, but you still have no hand, you’re still damaged. I did come to understand my parents though, and the forces that shaped them and made them the way they were. So my anger and bitterness did evaporate over the years.”

The late winter sun slips behind the stringybarks and shadows settle over the little school. Marsden will be here all day, attending to the never-ending administrative duties: arranging remote learning, rescheduling camps and excursions, responding to emails from parents, and all the time-wasting twaddle of the bastard bureaucracy. “I spend so many hours a week just answering letters from them, filling in forms, writing out meaningless statements,” he says of the bureaucrats. “I don’t know how many policies we have now; we have policies on everything. You’ve got to have the policies on the school website for the parents, so they can come after you when you’ve failed to adhere to a policy.”

The gang of choughs swaggers off into the bush. “You know what they do sometimes?” Marsden says. “They’ll abduct a young bird from another gang. The adults will communally feed that young bird and raise it as their own. Fascinating birds.”

I ask Marsden if he minds if I take a walk in the bushland behind the school before I go. He says that’s fine, but then stops. “Oh! I just remembered, there’s supposed to be a hunter coming in to shoot deer up there this weekend. I’m pretty sure he said Saturday, though. Or was it Sunday?” He gives a final smile and drifts like an autumn leaf back to the principal’s office. “I guess it’s a risk.”

Take Risks by John Marsden (Macmillan Australia) is out on September 28.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout