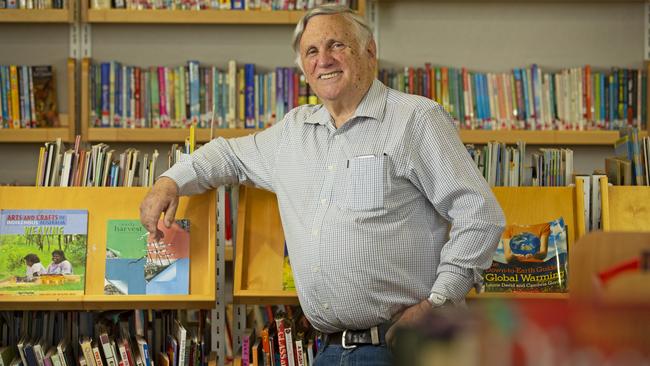

John Marsden puts middle-class parents to the test

John Marsden knows his advice about raising the next generation will win him few fans.

John Marsden is late. So late that when we finally connect, a day later than agreed, I can’t help but wonder how his great-great-great-great-uncle would have responded to such tardiness. Marsden laughs. “You’ve done your research!”

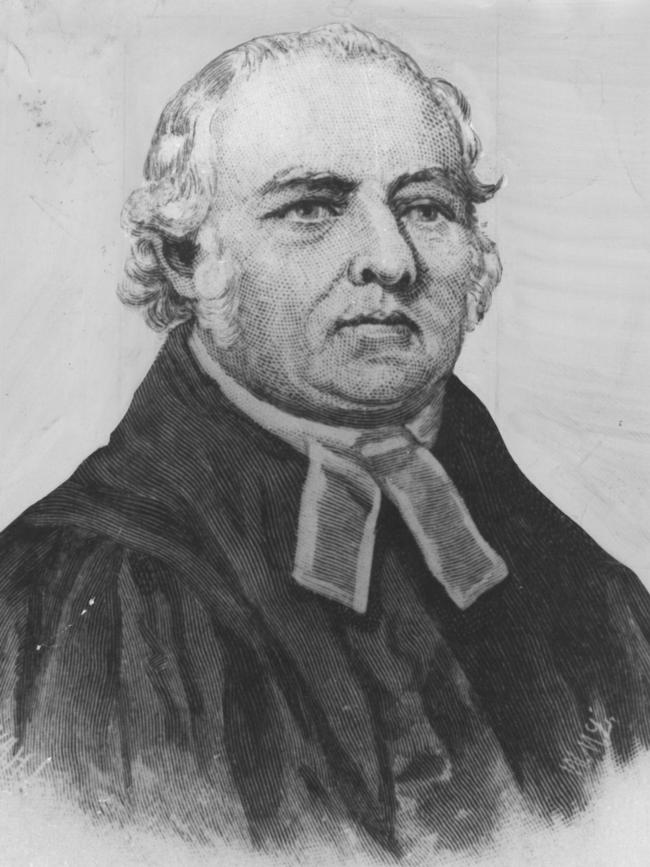

That uncle is Samuel Marsden, the man of the cloth, wool industry pioneer and magistrate who, through his time in the last job at Parramatta in colonial NSW, was dubbed the “flogging parson”.

As we chat, though, this ancestral link becomes anything but a joke. Marsden, 68, opens up about his own childhood and what he reveals is sad to hear.

We are talking by phone. It’s a Sunday morning but the award-winning writer of young adult fiction is at one of the two schools he has founded in Victoria’s Macedon Ranges.

This commitment to an alternative form of education now takes up most of his time. The schools, Candlebark, located on a forested estate near Romsey, and Alice Miller, at Macedon, have 380 students enrolled this year.

Marsden’s new book, The Art of Growing Up, is not a novel. It is a manifesto on what we are doing wrong with our children. That “we’’ is important: it’s the adults, in the home and in the classroom, who are to blame, not the children, not the adolescents, not the late teens.

Marsden, best known for the Tomorrow series of YA novels where Australia is invaded and occupied by a foreign power and teenagers form the guerilla resistance, is his own rebel with a cause. Helicopter parenting, he believes, and schooling based on rote learning and test scores rather than the creative use of knowledge is hurting our children.

He says this as a teacher, a YA writer and as a parent. He and his wife Kiri look after six sons, aged 15-25, all hers from a previous marriage. The two met 11 years ago when some of her sons were at one of Marsden’s schools. It would be fascinating to be a fly on the wall during their dinner conversations.

Here’s Marsden's message in a nutshell.

One, your child is not perfect. Two, your child will do bad things sometimes. Three, your child will be boring sometimes. Four, your child needs time away from you. Five, your child should take risks. Six, your child needs to feel fear. When one of his teachers asked to set up an “explosives class”, he didn’t ask her a question about it. He just told her to go ahead. “Our injury rate is spectacularly low,’’ he says of his schools, “but there are more grazes, bruises and scratches than most schools would have.”

Seven, your teenagers are better than you think, but you and their teachers are creating an environment where children are so babied that by young adulthood they are “20 going on six”. Eight, yes, it’s all your fault, because you lack “insight, imagination, understanding”. “We are seeing an epidemic of damaging parenting at the moment,’’ Marsden writes.

The familiar benign (and often malign) neglect of decades past continues, but the phenomenon of educated middle-class parents who don’t just love their children but are in love with them has reached a critical level.

Such parents agonise over every disappointment their child suffers, lavish them with praise when they manage to eat a green bean, record every moment of their lives on camera … manipulate their friendships and encourage their feuds, subvert schools by listening avidly to any criticism of teachers …

In short, they minimise their child’s transgressions, have no regard for those hurt by their child’s narcissism, block any attempts to create a culture with consistent and easily understood values, and blame others for the child’s aberrant behaviour. They are doing irreparable damage to their kids.

Later on he declares as though stating the obvious: “The most common parenting mantra is ‘I just want my child to be happy’. Their poor kids, I think when I hear this. What an awful fate to wish on them. Happiness is a relative term, so unless they experience unhappiness their happiness will be meaningless.”

A lot of parents will not like what Marsden says, and he knows it. He goes so far as to compare parents’ “today is a great day” reassurances to fascism. “I have told the publisher to put guards on the exits,’’ he says, thinking of events where he will discuss the book. “I don’t mind. I’ll take it as it comes. I’ve never been genteel.

“I do think there’s a need to be more direct in how we talk to parents because it — parenthood — has become this great untouchable area, this sacred topic, where you dare not criticise except in the most insincere ways.’’

When it comes to that malign neglect Marsden writes about, he knows of what he speaks. His childhood was spent in Kyneton, Victoria, Davenport, Tasmania and Parramatta. Reading his 400-page book I was struck by one paragraph about halfway through: “Unfortunately, my home life wasn’t excellent in every way. It was emotionally sterile, abusive and destructive ...” He does not mention this again in the 200-plus pages that follow. I ask him to elaborate and am taken aback when he does. I want to run his response in full, as he said it.

“Well, my father beat my brother and I a number of times, not every day, I mean a few times, but it was with a reinforced rubber hose which was about … I don’t know … I suppose it was reinforced with boiling water … really thick.

“He lost his temper, I suppose … at one time he said he was very angry with us and just tipped out of control. Beat us, I don’t know, 20 to 25 times, on the bum. The bruises were physically appalling after a few weeks. It made me afraid of men, afraid of pain, afraid of home.’’

He is able to laugh about the moralistic Samuel Marsden today — “Yeah, it’s funny. I think my father was carrying on that tradition” — but he has not forgiven the man who raised him, who died eight years ago. “What he did changed me as a person, fundamentally and irreversibly, and so forgiveness doesn’t achieve anything in any pretence of the word. I can let go of the past and all that, but I still have anger and hatred.”

Marsden says he was reluctant to talk about his childhood trauma while his mother was still alive. She died 18 months ago, in her late 90s. “It’s a big statement to make,’’ he says, “but she was emotionally arrested at the age of five or six and never developed beyond that.

“She was very rigid, very righteous, very judgmental, very critical, very self-centred, and neither of my parents where able to relate to other people. We never had a visitor in the house. I suppose in 10 years they might have had a dinner party two or three times, which involved days of scrubbing, vacuuming and dusting. Yeah, they were a very closed world.”

While the record shows Marsden has written one adult novel, the well-received convict saga South of Darkness (2014), it was in fact his second. In 1994, when his parents were alive, he published a semi-autobiographical novel, Lost to View, under the pseudonym James Horden. When I ask if it’s OK for me to mention this, he says, “Yeah, I might as well stop being coy about it … plus you’ll never find it anyway.’’

Even when he did decide to write under his own name, seven years later, drafting the book that became his award-winning YA debut So Much to Tell You, his mother demanded he use a different name. He did not and his mother, seeing herself as the selfish mother in the book, was “very angry, very upset and very resentful”.

How did Marsden survive this? First, he ran away from home. “I’m embarrassed about this,” he says, “because I was 18 at the time. It doesn’t have the romance of running away when you are 10.” Even so, he remembers the date: the Australia Day weekend of 1969.

A bright student, he went to Sydney University, doing law and arts, but dropped out and did a series of rent-paying jobs such as delivering pizzas, selling encyclopedias and working in a mortuary. He suffered depression, and today acknowledges the two “life rafts’’ that saved him: mental health counselling and books.

“I probably set an Australian record for the number of hours spent in psychoanalysis. It was painful but incredibly worthwhile. There’s no cure, though. You can’t erase the damage.’’

Before he was old enough to choose psychiatric treatment, “reading helped me a lot’’. “I read my way through childhood and adolescence and that was my survival. I’d go to the library after school and borrow three books, read them before the library shut and then take them back and get three more for the night. I probably set another record there. And, God, I lived in the world of those books.’’

The Art of Growing Up is full of advice, with chapter headings such as Effective Parenting and Making Schools Better. With that in mind I ask Marsden to sum up what he thinks parents and teachers should do today. He pauses for a while. “Well, take a few steps back and let your children blunder around and make their mistakes. Be down to earth, literally. Let them play in the rain, get muddy, explore wild places. There’s so many kids now who have never left the city and suburbs.

“Let them have their own daydreams, their own games, their own activities. Stop interfering, stop scrutinising. Don’t emphasise material gains. Value the abstract qualities, such as empathy and compassion. Those are more important than getting into medicine at the best university or getting the new Audi.’’

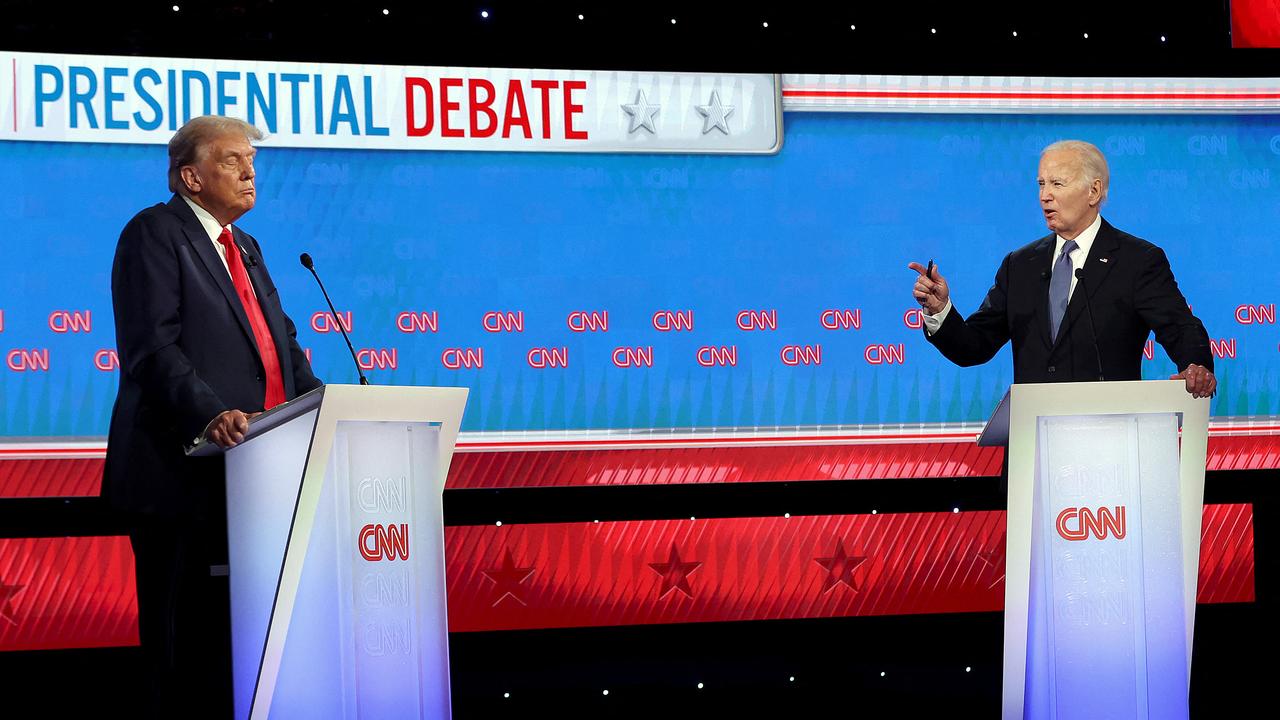

He adds, almost as an afterthought, that the adults most in need of growing-up lessons are our political leaders. “It’s a mess and it has had a powerful impact on the collective conscious of Australians, and young people in particular. There are no role models. For them, politics is just a bad joke.’’

The Art of Growing Up, by John Marsden, is published next week by Macmillan Australia (416pp, $34.99).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout