Hugh Lunn: My great leap through the bamboo curtain

A young reporter trying to enter “Red China” hears the colourful words of Maoist abuse.

When I decided in 1965, as a young, naive reporter in Hong Kong, to try to wheedle my way through the “Bamboo Curtain” into Red China, I came up against exactly the same semantic problems that Scott Morrison has encountered in recent weeks.

In 1965 China was a republic of 750 million people but, even so, Australia refused to recognise the Communist government of Chairman Mao Zedong 16 years after his revolution. We recognised, instead, the small island of Formosa (now Taiwan) off the coast as the true government of China.

So I was anxious to see what we were missing out on.

I dropped around to the Bank of China Building in Hong Kong, the Chinese Communist Party’s window on the outside world. It was opposite the Hong Kong Cricket Club where I had played for the Kowloon Cricket Club the day before and, aged 24, I decided to walk into the monastic foyer of the stone fortress.

Once past the pistol-packing Chinese guard, I spoke to a woman at the reception desk.

How could an Australian like me get a visa to go into China?

“You Australian are fashion-conscious coffee shop-dwellers,” she replied.

“No, we drink tea.”

“Australian are renegades,” she said.

What could she mean?

“You Australian are running dog lackeys of the Yankee imperialist aggressors,” she carefully explained, as if I should have thought of it.

The Chinese people back then were cut off from almost all the Western world and so had developed their own dictionary-derived brand of English — based on repeating acceptable government phrases (which couldn’t get them into trouble) over and over again … until even I knew them off by heart.

What’s curious is that, after becoming very much a part of the world in the past 40 years, China has suddenly returned to its strange Cold War isolationist Maoist lexicon of abuse that I thought had gone out with straw hats. Just the other day, the Chinese Communist Party newspaper, the Global Times, made headline news by out-of-the-blue describing Australia as a “lackey”, a “US running dog”, and “a giant kangaroo that serves as a dog of the US”.

Similar phrases poured forth from the New China Newsagency and the official People’s Daily in 1965 — aggressive and old-fashioned English words strung together, like, “Ideological disdaining deviationist self-indulgent bourgeois experts”. One of my favourites was: “The United States is a paper tiger, which, like a rat crossing the street, is chased by every passer-by.”

Scott Morrison will know he’s in very real political trouble if they start calling him a “double-dealing capitalist roader running-dog puppet lackey”.

So I left my Australian passport with the woman at the front desk, hoping for the best.

On my second uninvited visit to the Bank of China Building a few weeks later — because I had received a letter from Moscow regarding my planned rail trip — I got to see a higher-up official with his own office, a Mr Kiat.

“So Hu Loon,” he said, “your passport says you are a journalist. So you must know Australia does not recognise that our glorious Chinese Republic exists. So your passport is not valid.” He slid my blue document back across his desk as if it were contaminated.

I had been chastised by my Hong Kong colleague, the famous hard-drinking Sydney journalist Steve Dunleavy, for having “journalist” in my passport. Steve, a reporter by day and a bouncer in Hong Kong’s red light district by night, was adamant.

“Mate, mate!” Steve said. “The smart journo lists himself in his passport as a librarian or a history teacher or a lawyer or something else innocuous.”

This was a mistake I was going to have to overcome.

Knowing that the Brits continued to recognise China, and even pushed for it to be admitted to the UN instead of Formosa, I told Mr Kiat: “But this is a British passport,” and I showed him on the cover at the bottom in capital letters where it clearly said BRITISH PASSPORT and I showed him the gold crown on top and read from the inside cover: “In the name of Her Majesty Elizabeth the Second, Queen of the United Kingdom and of Australia, I request all those whom it may concern to allow the bearer to pass freely without let or hindrance …”

The Communist official was unfazed. He leaned across his desk and delivered his riposte.

“So Britain is your capitalist landlord, Hu Loon,” Mr Kiat said. “Do Australians live under colonial extortion with an unequal treaty like Hong Kong?”

I explained that England was seen as our “Mother Country” because it sent all its convicts to Australia. Instead of being impressed, Mr Kiat became agitated.

“Imperialist oppression, Hu Loon!” he said, standing up. “China suffered this capitalist outrage for hundreds of years until the revolution.”

Sitting down again he recovered his usual composure: “So, Hu Loon, why do you want to see somewhere that does not exist?”

“Because China is a closed-off society,” I replied. “I’ve looked into China from across the border; I’ve seen into China from Macau; and also from the top of Dog Teeth Hills on Lantau Island. So it’s simple, Mr Kiat. I’d like to see inside for myself.”

“Who do you represent?” he suddenly asked, suspiciously.

“I represent myself.”

“Are you taking part in idle individualism?” Mr Kiat replied. “Nothing is simple, Hu Loon. Western journalists are poisonous weeds because they are fiction experts who dwell on negativism. You will write deleterious stories about our successful struggle.”

That wasn’t true, I said. “China is a place of much interest to me.”

“So you are a bourgeois idealist?”

It was another question I didn’t have an obvious answer for. So I stood up to go.

“You should not feel denunciation,” Mr Kiat reassured me. “I understand the felicity of your struggle.”

Four months later I returned to the Bank of China Building during my lunch hour. “You must strengthen your assiduity, Hu Loon,” Mr Kiat said. “Your struggle has not received leniency.”

So I played my last card. I proudly slapped down a magazine on his desk — the Far East Architect & Builder — opened at the double-page spread displaying my article on Peking opera faces: how the actors learned by heart both the words and gestures and never improvised; how they played the same role for life. The colours of the clothes and the faces foretold the character. A blood-red robe embroidered with gold meant the character had supernatural powers. The hero always had pink cheeks.

I had tried to write something that might get me beyond the Bamboo Curtain, where even the world’s biggest newsagency, Reuters, couldn’t go. I didn’t know that Peking opera had been banned by the Communist regime.

Mr Kiat quickly clutched the magazine to his breast and said: “I will send this up to Canton. Joy Geen (goodbye).”

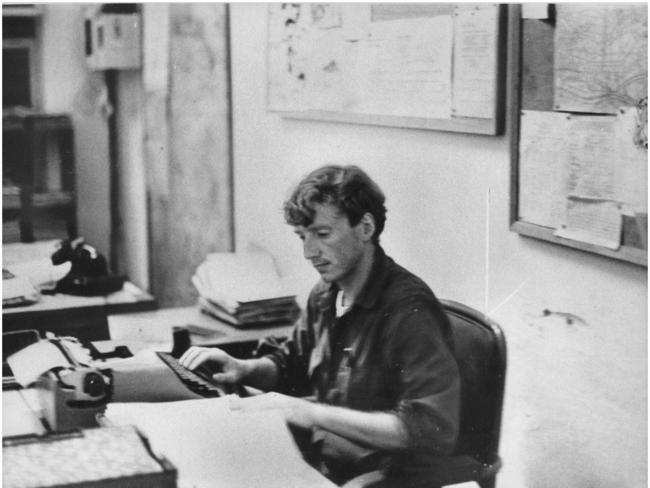

Several days later my English boss, Max Schofield, leaned over the typewriter and shouted loudly enough for everyone to hear: “There’s a Mr Keee-at been on the blower looking for you, Lunn. Reckons he knows you. It’s the first time I’ve ever had a phone call from Mao’s lot. What’s going on m’boy? Have the Communists capitulated?”

I ran the two blocks to the Bank of China Building. Mr Kiat had received a message from Canton. If I caught the train to the border on Monday morning “there might be a visa there waiting for you”.

Might wasn’t good enough. “Nothing in life is definite, Hu Loon,” Mr Kiat said. But this time he asked for my passport.

That night in Steve Dunleavy’s own nightclub the drinks were on me. “When I get out I’m going to have some great stories to write,” I told him. But Steve — whose reputation for fearlessness preceded him around the world — had an unexpected reaction. “When you get out? You mean, if you get out.”

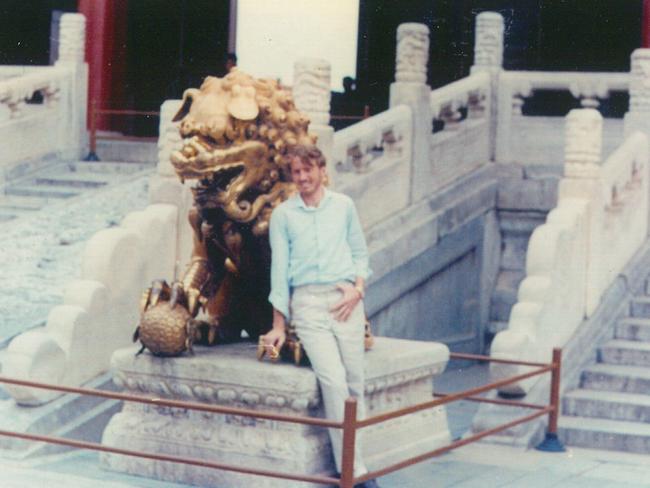

I did get into China and watched a million people marching up Tranquillity Boulevard past the Forbidden City through Gate of Heavenly Peace Square — all shouting for America to get out of Vietnam, get out of Latin America, get out of the Dominican Republic — and, reaching a thunderous crescendo: “America get out of the world!”

This was before the Cultural Revolution but I witnessed the early version of the Red Guards — the Young Pioneers — marching through the streets shouting that they were “the Socialist Vanguard who practise frugality and fight against excesses”.

The most interesting thing I learned back then was that China had what it called “blurred feelings” towards us because Australians were “the product of recalcitrant imperialism and chaos in Europe who had been sent to Asia by capitalist landlords as retribution on the labouring masses”.

Perhaps the best Scott Morrison can do right now is strengthen our assiduity, not feel denunciation, and believe in the felicity of our struggle.

Then once again China and Australia can share blurred feelings.

Hugh Lunn recorded his 1965 adventure through China in his book Spies Like Us (HarperCollins).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout