The living dead — fact or fiction?

Stepping on the toes of science and religion, cryonics generally makes bad headlines. So what’s real and what’s not?

Cryonics is a difficult science. Its credibility hangs by a thread. It presumes that, in the future, science can not only revive people preserved in cryogenic chambers, but that it can also cure the diseases that killed them. Otherwise they’ll die again. It’s a big ask.

Then there’s the touchy issue of “the soul”, whether your revived or transplanted brain or your memory downloaded to a computer is “you”, your spirit. Will “you” have an awareness?

There’s been a tiny ray of hope. In 2018 it was widely reported that Russian scientists had revived Siberian roundworms that had been frozen in permafrost for 42,000 years. Even if true, humans are a zillion times more complex than roundworms.

These reservations haven’t stopped companies pouring millions into building cryonic facilities and customers spending tens or hundreds of thousands to be preserved in them.

MORE FROM CHRIS GRIFFITH: How did this house survive an inferno? | The new bike you can ride on water | Fake news infecting health and politics | Watchful eye on the metadata watchers | A new angle on streaming

In Australia, Southern Cryonics plans to build and operate the nation’s first cryonic storage facility at Holbrook, in southern NSW. It’s been a long haul. The not-for-profit was incorporated in 2012, and it bought land at Holbrook in 2016. It has 27 founding members (prospective patients) and plans to complete building work this year.

It’s offering an earlybird membership rate of $50,000 for “one free suspension for themselves or anyone of their choice” until March 31, and $70,000 after that. The price will jump to $150,000 once the facility opens.

Cryonics generally makes bad headlines. It steps on the toes of science and religion. “Reanimation or simulation is an abjectly false hope that is beyond the promise of technology and is certainly impossible with the frozen, dead tissue offered by the cryonics industry,” says neuroscientist Michael Hendricks in MIT Technology Review. “Those who profit from this hope deserve our anger and contempt.”

Scientists generally regard cryonics as cold comfort for those seeking immortality. However, none of this has stopped its romantic appeal, the philosophical transhumanist discussions around it, and, of course, movies.

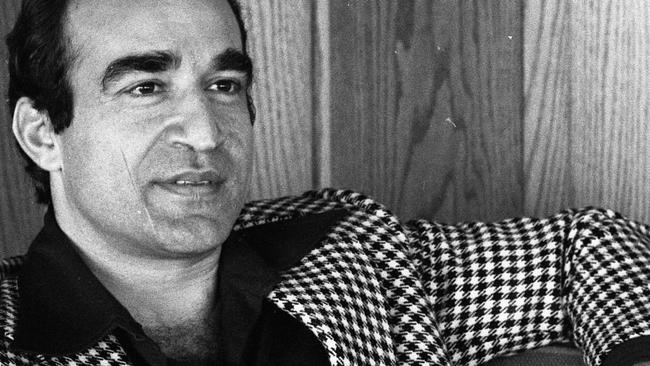

US filmmaker Johnny Boston is the latest to delve into the chilly world of cryogenics with 2030, which focuses on futurist, author and transhumanist Fereidoun M. Esfandiary, a cult figure known as FM-2030, who said he was born a century too early. Esfandiary changed his name to FM-2030 after declaring that the customary nomenclature is outdated.

Transhumanists explore the benefits and dangers of using emerging technologies to extend the human condition. Esfandiary had a wish to celebrate his 100th birthday in 2030, but fell 30 years short of this goal when he died of pancreatic cancer in 2000.

He is understood to be the first human who was vitrified, which involves preserving organs without forming cell-damaging ice.

In his movie, Boston presents what seems like a documentary of the events leading up to Esfandiary being brought back to life in 2030. Of course it’s all hypothetical, a simulation. The film is more about the philosophical discussions, the fears, hopes and, at times, opposition by the many people Boston interviews, as preparations to resuscitate FM-2030 proceed.

Boston told The Australian he met FM-2030 through his father’s contacts when he was a child and the transhumanist became a lifelong friend: “He was one of the first adults that spoke to me not like I was a kid, but like I was thoughtful. I think I was 11. I met him again when I was a teenager.

“He looked like a Bond villain and he had this weird name. And then I read his books, and the books were really, really interesting.”

Boston says he didn’t “jump on board” with all of FM-2030’s ideas but “he definitely made me think about things in a very different way”. His film begins dramatically with a narration about the limitations and fears of human mortality. The spectre of death hanging over us means we are never free.

“As long as we live in these fragile, biological bodies, survival emotions will dominate everything,” the narrator intones. A theological figure speculates that cryonics is a religion because it seeks to offer immortality. American roboticist David Hanson chips in, saying we need to ask questions about what is meaningful about humanity.

Boston explores the philosophies and mixed emotions and thoughts underpinning cryonics. “Who are we? Are we our memories? Are we something else?” he asks. Indeed, are humans nothing more than strands of DNA that in future can be replicated? Can we define what consciousness really is? Would creating us as code or as a human map negate the idea of a soul or spirit?

Boston says the movie uses real vision of FM-2030 and fresh content about him. “We also use a lot of stuff where he (FM-2030) was on Larry King and he was on various talk shows. There was all sorts of audio that we got from the archives.”

The exception to this realism is the simulation of FM-2030 returning to life in 2030 in a robotic body that looks like a young version of himself. “It’s surprising how many people by the end believe it’s real. We’re pleased that people experienced it in that way,” Boston says.

FM-2030’s brain is preserved at Arizona’s Alcor Life Extension Foundation, which Boston says is at the cutting edge of cryonics.

The interest in cryonics, meanwhile, continues despite claims it is quackery. Alcor says on its website that it is preserving 129 male and 46 female patents, and has 1290 signed-up members — people who have completed full legal and financial arrangements for cryopreservation with Alcor.

In some cases the whole body is preserved; in others, such as FM-2030’s, it’s just the brain, in the hope that one day it can be attached to something or downloaded to a machine, and consciousness restored.

Alcor admits it cannot bring cryopreserved people back to life with current technology. “Revival of today’s cryonics patients will require future repair by highly advanced future technology, such as molecular nanotechnology.”

That puts paid to Esfandiary bouncing back in 2030 as Boston’s film simulates. But this film is more about transhumanist philosophy and hope than assessing the science. It’s about the journey rather than the destination.

Boston says he has been making movies for more than 25 years. “This is my full time career,” he says. “I've made a bunch of documentaries. I've produced some movies and my daytime job is to make films for companies and institutions ranging from IKEA to various banks and so on and so forth.”

Boston has also launched a YouTube channel called Galactic Public Archives which contains an eclectic mix of clips about futurists, artificial wombs, the future of democracy, the gig economy, meeting an alien, and relationships. It will keep you awake at night thinking, if cryonics and transhumanism doesn’t already do that.

The film 2030 is available through iTunes.