How did this house survive an inferno?

Architects and engineers are investigating how to make our homes more resistant to bushfires.

Bushfire victims devastated by the loss of homes face important decisions when they rebuild. How can they protect themselves and their home from another blaze?

Australian standards govern the building of new homes in different areas of fire risk.

But there are many choices to be made along the way.

No home is entirely fireproof unless you live in a specially constructed bunker. However, you can dramatically reduce the risk of your home catching fire from windblown embers if your deck is made from fireproof materials and you use the correct cladding. Fire-retardant materials can give people precious time to escape.

It’s early days with this. This fire season is not over. It will take months for contractors to clear rubble from destroyed homes. Insurance payments need to be finalised and government grants sorted before rebuilding takes place.

More than 3000 homes have been destroyed, so a shortage of tradespeople is likely in the rebuilding phase. Reconstruction could take years. Nevertheless with climate change upon us, we need to build for a hotter, drier future, with an increased likelihood of more ferocious fires.

MORE FROM CHRIS GRIFFITH: A new angle on streaming | Light and power | Gadgets for a new decade

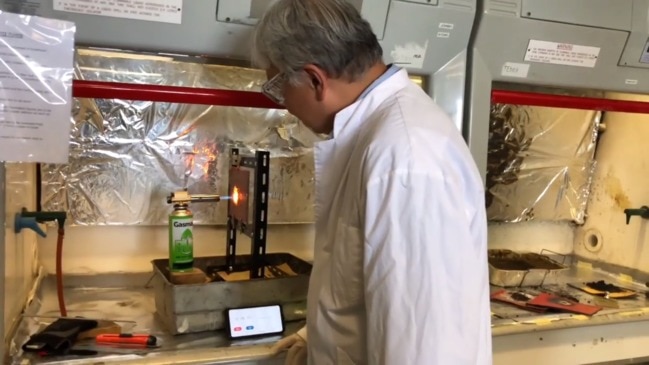

The University of NSW school of mechanical and manufacturing engineering and an industry partner have been developing fire-retardant paint.

“It can be sprayed on to buildings and it can withstand fire for half an hour at 1000C with no problems at all,” mechanical and manufacturing engineering professor Guan Heng Yeoh tells The Australian, adding it will cost from $2 to $4 a square metre.

He hopes to make it available this year: “We’re looking at a number of manufacturers to make it large scale and really roll it out.”

The university also is researching using organic compounds to make retardant substances that are biodegradable and non-toxic, such as extracting organic compounds from prawn shells, oyster shells and plants.

Support organisations and architects are gearing up for lots of inquiries from those contemplating a rebuild.

The Bushfire Building Council of Australia, a non-profit body, offers access to independent experts who can help people build better fire-resistant homes and retrofit existing ones.

BBCA chief executive Kate Cotter also anticipates a need from those whose homes survived to reassess risk and retrofit for the next fire.

She says the first step is understanding how buildings catch fire. Embers are the No 1 cause, followed by heat radiated from another burning object, such as the house next door. Making a building fire-resistant requires attention to detail, but it doesn’t have to be expensive, Cotter says; it means “no combustible elements externally, no combustible cladding, non-combustible decking and non-combustible window frames”.

Decking made from fibre cement, such as HardieDeck, looks attractive and offers fire resistance, yet it costs about the same as regular decking, she says. Tiles are another option. Fibre cement cladding used with fire-rated plasterboards can offer a pleasant timber look. And houses can be constructed with metal frames and fire-resistant, toughened glass.

“That helps prevent any flying debris impacting the windows, it also adds some radiant heat protection for when the fire front moves through,” Cotter says.

Shutters provide daily sun protection and also protect windows during fires.

Homeowners should create a 10m buffer around their home free of combustible objects. On new estates, houses shouldn’t be built within 10m of each other to avoid radiated heat, Cotter says.

Roofs with simple lines are better. Leaves and embers can be caught in a complicated roofline. Roofs need to be secured properly.

Homes can be designed for “slow loss of tenability” if a fire happens to take hold. Firewalls, fire doors and other internal designs provide more time to flee to safety. Embers can be kept out if homes are built on concrete slabs and underfloors are closed off.

“You have to have no gaps greater than 1.8mm anywhere in the house,” Cotter says.

She says with the right materials, you can build a home with an entirely comfortable design that’s fire resistant. “It’s about rethinking what the materials are, not as much about being limited by design.”

If you don’t want to build your own fire resistant home, you could engage an architect who can offer a ready made fire resistant solution.

Bushfire architect and Queensland University of Technology academic Ian Weir has been building fire-resistant homes for 25 years, including about 10 after the Black Saturday fires in Victoria in 2009. One problem after Black Saturday was the disappointing take-up of these architecturally designed homes.

He says some of these fire-resistant homes looked uninviting and were expensive. It was a lesson learned: “Architects generally work in a bit of a rarefied atmosphere for one-off clients.

“While they can come up with innovative solutions for the general public, it doesn't resonate with them.”

Weir plans to make one of his designs, Karri Fire House, available as a lower cost-option. “I guess I've been seeking to work in a bit more towards the affordable market.”

He designed the fire-resistant home with his partner, Kylie Feher. The exterior of the Karri Fire House is made of non-combustible material and it has concrete walls and 200mm-thick concrete floors.

“It’s got a big, generous veranda and it’s very open and expansive to the landscape,” he says.

Weir is talking to suppliers so that all the services to build his house are available in one spot.

Melbourne architect Clare Cousins also was involved in fire-resistant housing after Black Saturday, with her firm offering pro bono design: “There was a call-out to architects to do that … to develop a low-cost, flexible kind of home that can be adapted to various sites. So we put one up. The design has since been used on a number of rural properties.”

She already has taken calls from people interested in it and was considering making it available as an off-the-shelf product.

She says The Institute of Architects is looking at co-ordinating efforts to assist bushfire victims through the organisation Architects Assist, which can call on the services of 1000 graduates and registered architects.

There are examples of fire-resistant housing surviving the fires, such as Ron Weir’s home at Rosedale, on the NSW south coast, which remains standing after fire swept through the area on New Year’s Eve.

It survived radiant heat generated as the homes next door burned to the ground.

But Geoff Hanmer, adjunct lecturer in architectural structures and construction at UNSW, is worried that fire-resistant homes may give occupants a false sense of security as fires approach.

“With current technology and with our current firefighting services, it’s not possible to stay and defend a house which is conforming with the Australian standard, because you can’t guarantee that it won’t burn down,” he says.

State Governments and local authorities have lots to do before the housing issue is addressed. In NSW, a spokesperson for Deputy Premier John Barilaro says the NSW Government currently is focused on the clean-up.

“Regarding the rebuild and materials to be used, it is too early to determine at this stage as fires are still burning and assessments are still underway,” the spokesperson says.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout