Frederick Forsyth: ‘My wife Sandy knew that her life was over. We both knew it’

As The Day of the Jackal returns, Frederick Forsyth talks about the death of his wife, foiling a Putin plot and what he really thought of John le Carre.

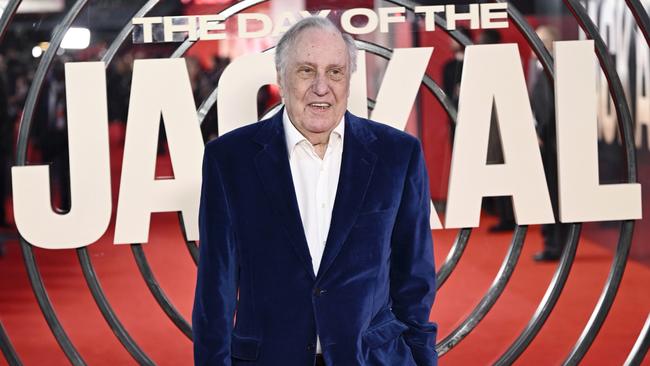

The night before the morning of my meeting with Frederick Forsyth at his stately bungalow in a leafy Beaconsfield in Buckinghamshire, he had, as I had presumed, attended the London premiere of Sky’s new version of his first and most famous thriller, The Day of the Jackal. What I could not have known was that five nights earlier, his wife had died following years of opioid abuse.

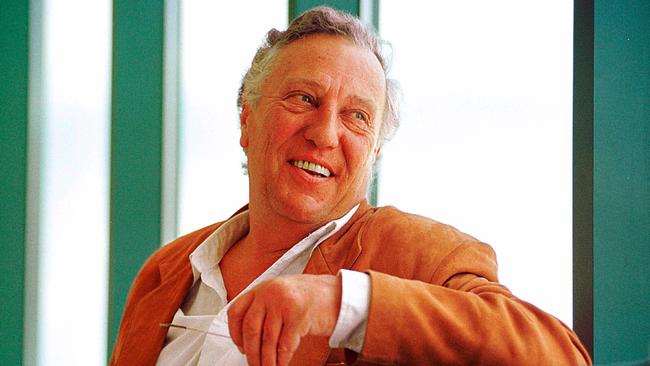

They had been married for 30 years, their marriage seemingly ordinary in contrast to his sensational career as a journalist, novelist and part-time MI6 spy, but Forsyth, 86, has no more difficulty in discussing her death than the new life television is about to grant his masterpiece. The secret of his old-fashioned charm, I discover, is a preference for absolute honesty.

It is a triumph for any author when one of their works survives the test of time to be translated to the screen more than 50 years after publication and, in this case, almost as many years since the famous Day of the Jackal movie starring Edward Fox.

The new series, written by Top Boy creator Ronan Bennett, credits Forsyth as “consulting producer”. I ask what that means. “It means the phone rings about once,” Forsyth replies. “To put it brutally, if they had made it and called it something else, I couldn’t have sued for plagiarism.”

He is wearing a pastel jumper, sitting in an enveloping armchair. A few years ago, one of John le Carre’s mistresses mocked Forsyth’s “phony colonel voice” and sneered at this son of Kentish shopkeepers who was her Sherborne-educated lover’s rival in the espionage fiction business. His London flat, claimed Suleika Dawson in her racy memoir, possessed books only with his own name on the spine.

But here in Buckinghamshire, his shelves are populated by other people’s histories and biographies. Yes, he may at heart be a journalist and therefore irretrievably below the salt, but his apprenticeship on the Eastern Daily Press in Norwich followed two years learning to fly jet fighters in the RAF.

The new Jackal is, he implies, less an adaptation than an “inspired by”. The original story about an early 1960s plot to assassinate France’s president Charles de Gaulle is transposed to the present day with “the Jackal” hired to kill a German politician and then a free-speech tech entrepreneur. Forsyth’s famous scene featuring a watermelon used by the Jackal for target practice survives (unlike the watermelon) but such nods to the source book are infrequent. He is not complaining. A conspiracy by extremists angered by Algerian independence would mean little to viewers today who have barely heard of de Gaulle. Forsyth thought the first episode “convincing” and declares Eddie Redmayne, 42, who plays the Jackal, a “nice young man”. When he says 10 episodes seems an “awful lot”, I reassure him that the first five are gripping and that I want to see the remainder as soon as possible.

“To be frank, I get the royalties,” he says, his thumb and fingers making the international sign for filthy lucre.

It is only right that he is being handsomely rewarded given he sold all rights to the 1973 film for just £20,000. After all, without the title the drama would fight to be noticed. And it is an unforgettable title. He tells me he chose jackal for the assassin’s codename because most of the rest of the applicable animal kingdom, from cobra to jaguar, had been taken and “you can’t call somebody the Ocelot”. Before his intervention, he muses, a jackal was “a nice little foraging animal from the savanna”.

He wrote the book out of poverty, having fallen out with his bosses at the BBC over their craven adherence to Britain’s pro-Nigerian stance in the country’s civil war and its indifference to the mass starvation of Biafran children on the losing side. Forsyth returned to Nigeria in 1968 as a freelancer but also reported back to MI6, elements of which distrusted the Foreign Office line. By Christmas 1969 he was back in England and broke. After 35 days’ writing in a friend’s flat in London he had finished The Jackal and spent the spring and summer searching for a publisher who could see beyond the obvious objection that de Gaulle had not been assassinated. The suspense, he finally persuaded the editorial director of Hutchinson and then many millions of readers, came from the hunt for the gunman.

The novel has been called journalistic fiction, which sounds like a le Carre put-down but is really a compliment to Forsyth’s research. As a Reuters correspondent he had followed de Gaulle on his official outings from the Elysee Palace in case there was an assassination attempt. In August 1962, soon after Forsyth’s arrival in Paris, the president’s car duly came under fire and a bullet narrowly missed de Gaulle’s nose. Forsyth would drink with the president’s bodyguards and later consulted them in their retirement when writing The Jackal. “I still think to this day I wrote my stuff as journalism. It was like a long dispatch, some of it. All based on facts, based on reality.”

I compare de Gaulle’s spared nose to Donald Trump’s recently scathed ear. Forsyth nods. The trouble with bombs is that they always go wrong: “So the rifle, for me, is the only viable way of carrying out a high-level political assassination.”

His own lucky escapes include outwitting the Stasi while reporting in East Germany. In 1973 he foiled Vladimir Putin, who was head of the KGB in Dresden. The MI6 had asked Forsyth to pose as a tourist and retrieve a package from a Russian colonel secretly working for the West. Putin had been tipped off but, greedy to take the credit for himself, did not alert the Stasi. “He was too vain. He didn’t confide in them. He thought he would stop me himself but he quartered the wrong road. I wasn’t on that road. I was on the other one. So I got through the border with about 10 minutes to spare. Or maybe less.”

An earlier close shave was almost literal. A la de Gaulle and Trump, a bullet skimmed through his hair in Biafra and embedded itself in a doorpost. “I have to say, I have had the most spectacular luck all through my life. Right place, right time, right person, right contact, right promotion – and even just turning my head away when that bullet went past.”

I wonder where his courage comes from. Genes? His parenting? Surviving bullying at his school? He says it was never about deciding to be brave. “It’s more, ‘I want to do this and, OK, there’s a risk involved but I’ll take all possible precautions to avoid the risk and then go ahead.’ ”

What is also puzzling is why readers of The Jackal find themselves taking the side of the assassin rather than his intended victims. He refers me to Britain’s dislike of de Gaulle for thwarting its entrance into the common market (when we joined in 1973 it was on the wrong terms, says Forsyth, a still-believing Brexiteer). If this was ever a convincing explanation, it cannot be one now.

The TV series does not feature de Gaulle, yet I still rooted for Redmayne. I suggest it is his Jackal’s solitariness that attracts us. “It’s one man against a huge machine. We don’t like machines, so one guy even trying to kill a human being, taking on this vast machine of government, secret intelligence service, police and so on, has appeal,” he concedes.

It is not hard to read Forsyth’s loner personality into this generalisation. His 2015 memoir was called The Outsider. In it he wrote that long periods of solitude began for him as a circumstance, became a preference and finally, as a writer, a necessity. When we watch a writer socialise, he said, we see half of them: “The other half is detached, watching, taking notes.”

And it is now, knowing that for some years his wife has been in a nursing home, that I ask whether these days he is not merely solitary but lonely.

“Sandy died last Thursday.”

I’m so sorry, I say, shocked. “The thing about it is we both knew. Sandy knew and wanted to go. She knew her life was effectively over. She was lying on a bed in a care home that she would never leave. Didn’t want to watch TV any more, listen to the radio any more, read any more, write any more. She just lay there and stared at the ceiling and I would go and sit with her, hour after hour. And then when I left she became tearful and asked, did I have to go? I’d say, ‘I’ll be back tomorrow.’ So effectively for the last year, that was my life, going up that road to see her.”

He sat with her the night she died. “At 2am, she said, ‘Go.’ I left. They called me at 4.30 and said she’d just gone. I went back and she was just lying there, at peace at last. So, for her it was really finding peace and because it was so predictable and, for her, desirable, the grief was mitigated. Still, 36 years is a long time to be with somebody. We were both in second marriages. She was 40, I was 50.”

How did she become ill? “Pill-taking. She was a hypochondriac and she took pills, unfortunately, for imaginary illnesses, which in fact created the illnesses until finally in this house (3½ years ago) she collapsed. I couldn’t get her into the car. I had to call an ambulance. The ambulance men came.

“They did a brief prognosis on the floor and said, ‘No, this is a hospital case.’ Took her to the hospital, where they examined her and said, ‘You’re a very ill woman.’ And after that it was a litany of hospital, care home, hospital, care home, involving eventually five hospitals and five care homes because she never liked any of them and begged me to move her, which I did. But the next one would be the same.”

His first marriage, to model Carrie Cunningham, by whom he had two sons, ended amicably in 1988 after 15 years. When he met Sandy Molloy she was in the film business and had been Elizabeth Taylor’s personal assistant. “I had two long marriages and they took me from age 35 to 86. And I didn’t fool around and nor did my wives. So we were … what’s the word?

“Conventional. That side of my life. The unconventional was the harum-scarum weird things abroad.”

His loyalty, I think to myself, contrasts with the lies le Carre, aka David Cornwell, told women. Is this the difference, I wonder, between fiction’s two spymasters: le Carre, the professional spook, was addicted to deception; Forsyth, the journalist, to the truth.

“Yes. It could be, yes. But Smiley (in le Carre’s novels) was always after the truth in as much as it was Smiley’s job to unmask the traitor high in the MI6,” he replies judiciously. “The reason I got, not miffed, but a bit mocking, was that le Carre worked for MI6 when it was safe as houses and never even served in an embassy. I was behind the Iron Curtain.”

In truth, the world needed both men’s works. I know, however, which author I would have trusted with my life.

THE TIMES

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout