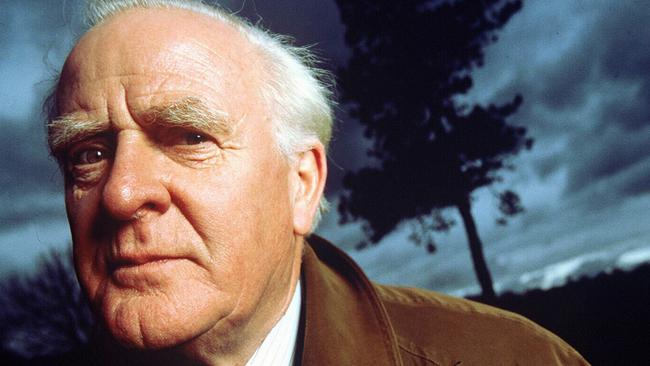

Straight out of a John le Carre

The master British spy novelist is dead and his death marks the end of an era that might have seemed over long ago.

John le Carre is dead and his death marks the end of an era that might have seemed over long ago. The man born David Cornwell 89 years ago was the supreme spinner of yarns about the Cold War but he was also the writer who created the mythology that enabled the world to put a name to its treacheries, its double agents, its Pyrrhic victories and sad defeats.

And he was also, beyond this, the most highly regarded popular writer since God knows who —Raymond Chandler, GK Chesterton, Somerset Maugham?

Le Carre’s sheer success and his shimmering achievement keep backing into each other and confusing every issue.

Graham Greene famously called The Spy Who Came in from the Cold “the best spy story I ever read”, which sounds right until you remember some of his own. John Updike, that formidable novelist who doubled as a brilliant critic, said: “Le Carre’s prose has an overheated expertise about it, as if it wished to be doing something other than spinning a thriller.” Yet it was Updike himself who said elsewhere that to create a great popular archetype might be a greater thing than to create a work of art.

In all sorts of ways le Carre enjoyed the best of all possible worlds. When The Spy Who Came in from the Cold was published in 1963 it pretty rapidly went to the top of the bestseller list in those days when the same fate could befall undoubted masterpieces such as The Leopard and Doctor Zhivago. Victor Gollancz paid the book, which has claims to be the finest thing le Carre wrote, the supreme compliment of a red cover rather than his usual yellow one for thrillers. Is its hero — very much of the whiskey-soaked, self-dismissive kind — an archetype? No, Leamas is a superbly realised individual and the bleak story that culminates in his moment of heroism is incapable of any formulaic repetition.

The Spy is a towering one-off thing. It’s also the occasion for one of le Carre’s ambiguous moments of great good fortune because when it was filmed in 1965 by Martin Ritt the portrayal of Leamas by Richard Burton, the biggest star of the day —and with flawless support by Claire Bloom as the young lefty girl and the great Oskar Werner as the Jewish East German — the film was at least arguably superior to the book.

And then this happens again with the figure who is le Carre’s archetype –– his great contribution to the well of captivating stock figures in the popular imagination — Smiley. Le Carre writes Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and it is filmed lavishly and expertly for British television, at appropriate length, with Alec Guinness as the mild understated spy with a calm and a temperateness that masks his steely determination.

Le Carre admitted — in fact seemed grateful to admit — that Guinness had in fact transfigured the character so that, as he was writing the book’s successor, Smiley’s People, he was conscious that the great actor had enlarged and enriched the viable character: he had quirks, he had subtleties, he had a kind of radiance that le Carre hadn’t quite dreamt of, though he had provided the outline.

All of which had its continuance when Guinness went on to play Smiley in the miniseries of Smiley’s People too. You can watch them on Amazon Prime together, and the streamers also will deliver to you Florence Pugh, who can be accused of surpassing her book form original in the miniseries of one of le Carre’s strangest books, The Little Drummer Girl (1983), about spies and performers and their interface.

That’s true of the expanded superb version of The Night Manager with Hugh Laurie at the height of his latterday saturnine powers together with Olivia Colman and Elizabeth Debicki.

But le Carre was built for the highest kind of fame — the deepest possible penetration of public sensibility –– even if you balk at Philip Roth declaring of A Perfect Spy that it was “the best English novel since the war”. This might seem odd in a world that includes Greene’s The End of the Affair or Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited —and then there are those outlanders Samuel Beckett and Muriel Spark.

But A Perfect Spy (1986) is a pretty extraordinary book and it’s the one where Cornwell exposed his blacking factory, the trauma that may have been the source of his deepest inspiration and creativity, the great villain and con man who was his father, Ronnie Cornwell. Le Carre’s father used to throw vast expensive parties — say for Don Bradman’s Invincibles cricket team –– while failing to come up with the cash for his son’s school fees at Sherborne. He would back members of parliament and later end up in jail for fraud. Le Carre had the distinct memory — from whatever pit of nightmare or disturbed recollection — of his father glimpsed from a window, behind bars in traditional jailbird dress. Cornwell pere was the kind of con man who broke his son’s heart and ruined lives.

Le Carre said: “It took me a long while to get on writing terms with Ronnie, conman, fantasist, occasional jailbird, and my father. From the day I made my first faltering attempts at a novel, he was the one I wanted to get to grips with, but I was light years away from being up to the job. My earliest drafts of what eventually became A Perfect Spy dripped with self-pity: cast your eye, gentle reader, upon this emotionally crippled boy, crushed underfoot by his tyrannical father.

“It was only when he was safely dead and I took up the novel again that I did what I should have done at the beginning, and made the sins of the son a whole lot more reprehensible than the sins of the father.”

This is judiciously put and it can be read in the stand-out piece in le Carre’s book of memoirs, The Pigeon Tunnel: Stories From My Life, which contains the New Yorker essay Son of the Author’s Father, which is one of the more extraordinary acts of remembrance ever committed to paper.

Le Carre paid to get his father out of jails around the world and this essay is well worth the price of the memoirs because it indicates what a heartbreaking wretch of a man his old charmer of a dad was.

When they did a fine compelling version of A Perfect Spy on television with Peter Egan as the character based on the younger le Carre and Ray McAnally as the old scamp of a father, David Cornwell was deeply unimpressed. He rang Guinness and said, “Did you watch that bit of rubbish?”

Was it because the dramatisation exposed that the great game of espionage — and A Perfect Spy is le Carre’s deepest examination of the moral ambiguities and duplicities of the double agent –– will always play second fiddle to the old destroyer of a father who could have sold the Aga Khan shares in slices of the moon?

Or was it that le Carre would have been happy only if an actor of absolute lordliness –– surpassing even Guinness –– such as Laurence Olivier had been assigned the role of the father he was always bailing out?

He tried to buy his father a farm to keep him quiet and the old rapscallion said, “You want to pay your father to sit on his arse?”

When Ronnie Cornwell died in his late 60s, his son David felt nothing. Then he vomited over and over.

Le Carre was obviously an extraordinary man and he resented the ambiguity of his reputation, the pivot between entertainment and literary worth: “In the eyes of so many of my peers, I have never been a novelist at all — just a maker of successful artefacts. A rich non-entity … I’m very tired of apologising for my success.”

English novelist Nicholas Shakespeare said of him, “In his company I felt exhilarated and engaged. I found him courageous, generous, complicated, competitive, touchy, watchful, suspicious, and incineratingly honest, although perhaps not in every single instance about himself, but then who is?”

As a boy le Carre hated school at Sherborne and ran away to Germany (which was always a country whose language and culture enthralled him). He came back and went to Lincoln College, Oxford, where he was recruited by the secret service.

Recalling his subsequent days at the British embassy in Bonn his first wife Ann —the same name as Smiley’s –– said when the subject came up in A Perfect Spy, “I always suspected David was working for the other side.”

In an interview with English journalist Rod Liddle he admitted to the temptation. “When you spy intensively and you get closer and closer to the border it seems such a small step to jump and, you know, find out the rest.” He later said that it opened a door to a world beyond good and evil and that “it felt like betrayal but it had a voluptuous quality”.

In relation to all this, it’s worth bearing in mind that le Carre had a distinctly histrionic quality that was wholly compatible with his seriousness. He looked after British prime minister Harold Macmillan at the Bonn embassy on one occasion and after he had helped him up the stairs, Supermac asked his name. “Cornwell, sir!” “Cornhill. I shall remember that.”

He had a stint teaching at Eton for a couple of years where one of his students was Ferdinand Mount, who would go on to write speeches for Margaret Thatcher. He met Thatcher, whose courage he admired despite his lifelong Labour loyalties. He loathed Tony Blair. “I thought Blair was lying when he denied he was a socialist. The worst thing I can say about him is that he was telling the truth.”

It was a relief to le Carre when he could admit he had done a stretch with the secret service. They were the people who had insisted on the nom de plume. But he came out into the sunlight when he admitted to his time in the shadows.

His reputation depends on the fact he captivated every kind of reader, including the most literary and rigorous. He was a master not only of the words that could keep us turning the pages but of the extension of those words into the big-time dramatic forms of the age.

Recently I watched Sean Connery in Fred Schepisi’s film of The Russia House — and it’s superb with its script by Tom Stoppard — but none of it would be there without le Carre in the first place.

With the end of the Cold War, le Carre arguably lost his eternal dialectic and ambiguous moral axis. But the later books, even when they find themes that are less mighty — the wicked pharmas, say, in The Constant Gardener — always have a surge and energy, a seriousness that ballasts the yarn spinning. In A Most Wanted Man, the one that led to one of Philip Seymour Hoffman’s last films and was directed by Anton Corbijn, there is a description of a figure accused of terrorism. And the final book, Agent Running in the Field, although in a minor key, is beautifully executed.

Whether you consider le Carre a great literary artist or just a great trashmeister he was a great something and in fact either label seems inadequate. They’re liable to read him forever with a fair degree of enthralment. He brought to the art of shaping his spy stories the dedication of a master craftsman.

Le Carre’s books are not perfect and sometimes they lapse when they are most ambitious, but they incarnate a vision that is part of the furniture of everybody’s mind. To be such a realist and romancer at the same time is an extraordinary achievement.

David Cornwell. October 19, 1931-December 12, 2020

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout