Japanese sake breweries: rice wine makers Oita and Hakusen

The Japanese produce sake with industrial precision and without any of the fuzzy romance of winery cellars.

There may not be a drink more widely found but less understood in Australia today than sake. It’s bobbing up on trendy wine lists around the country but if you ask your local sommelier how a specific example is made or even just to explain the various classifications and styles available, you’re more than likely to be met with a blank look.

And who could blame them? There are scant digestible sources of information available online for an English audience, and sake labelling makes even the most obscure European wines look consumer-friendly.

So what’s a curious drinker to do? In an attempt to learn more about a drink that I knew I liked, but little more, I made a detour to two breweries on a recent holiday in Japan.

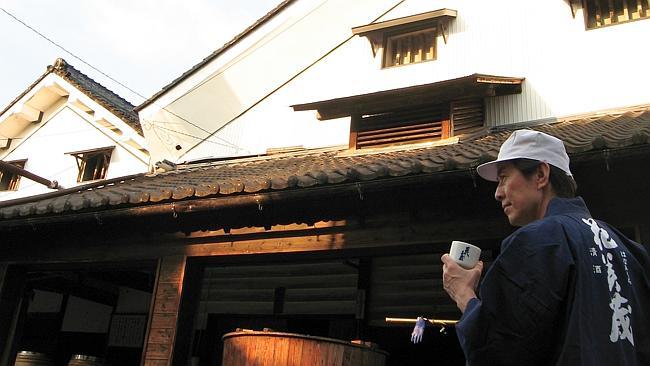

First up: Oita brewery in Hida-Takayama, a charming mountain town four hours from Tokyo by train. Founded as a front for a local ninja spy operation, today it is run by the extremely cheery 15th-generation brewer Hideo Oita, who assures me his family gave up espionage long ago.

I arrived hoping for an hour or so with Hideo-san. I staggered out of Oita’s historic shop four hours later, frankly overwhelmed by the generosity of my host.

After a quick history lesson over some green tea, the tour began, starting with the massive rice milling machines that operate 24 hours a day during brewing season (October to March).

From there, Hideo walked me through the entire process of making sake, with the help of his head brewer. Walking through room after room filled with pumps, presses and pipes, I was left with a real impression of exactitude and care.

Take, for example the special cedar rooms used for producing daiginjo, the highest possible grade of sake. There, small volumes of rice are spread across wooden crates, and seeded with yeast spores using something resembling a salt shaker. The head brewer told me he aimed to get exactly five spores on each grain of rice. That precision creates an incredibly elegant and refined sake, as I discovered during the tasting that concluded my time at the brewery.

The next day I was off to Kawabe, a sleepy town three hours south of Takayama, to visit Hakusen Shuzo. This is another brewery with an extensive and proud history, which was explained to me by vice-president and fifth-generation brewer Yuki Kato over more tea.

Hakusen Shuzo is actually most famous for its mirin, a rice wine usually thought of as a cooking ingredient.

But, according to Kato, mirin is Japan’s “original Red Bull” and has been used by tired workers for centuries as a pick-me-up. Unlike the watered-down stuff you’ll find in your local supermarkets, Hakusen Shuzo’s mirin, sold under the label Fukuraijun, is dark, savoury and only slightly syrupy.

Before moving on to the brewery’s excellent sake, labelled Hanamikura, I was treated to some of the pressed rice grains left over from the harvest, a rare delicacy sold as a slightly alcoholic sweet, or baked into cookies.

Perhaps the most striking thing about both breweries was how unashamedly industrial they are. There’s none of the fuzzy romance you’ll find in winery cellars. Winemakers often defer credit to the quality of their vineyards and hide their science beyond notions of intuition.

The theme most often repeated in my visits is that a brewer’s expertise matters above all else. These producers are proud of the precision of their craft.

No article on Japanese tourism is complete without a note about rules and customs. Despite best efforts, I broke a lot of them.

Business cards are extremely important in Japan, so any introduction without them entails an awkward silence. I’m fairly tall, turning large stretches of both tours into a balancing act as I tried to look natural in comically small slippers.

But my hosts were willing to look past these sins and ignore me as I struggled to complete the put-shoes-on-while-standing manoeuvre without falling over. (I promise it’s harder than it sounds). Both brewers were consistently warm, generous and excited to teach.

As is often the case when travelling in Japan, simply organising these visits was the hardest part. Sake breweries generally lack a cellar door and the vast majority do not have English-speakers.

Arranging these appointments required a lot of back-and-forth with Australian importers and tourism boards in Japan to find an interpreter. But once again, as is often the case in Japan, the effort was rewarded with a deeply memorable experience.

Spending two days in the Japanese countryside won’t make you a sake expert but it anchors the drink in a place and culture, and it’s that kind of context that sticks with you.