George Calombaris empire collapse: Not just the butter spread too thin

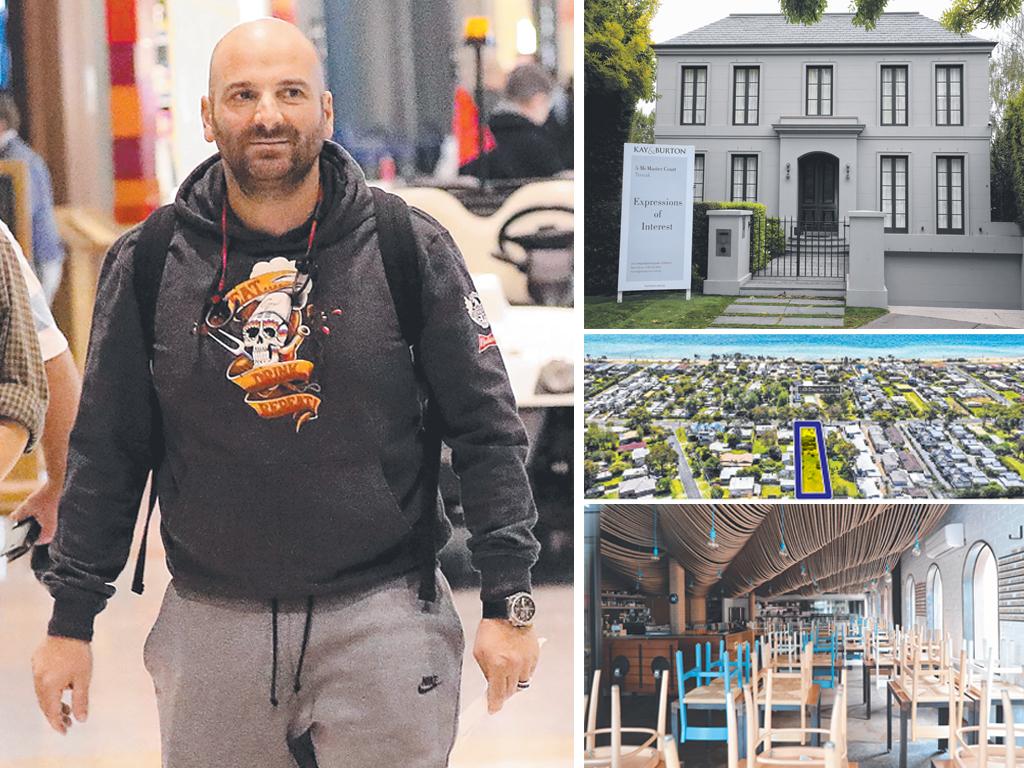

Ten years later, it seemed all flash cars and Toorak mansions for George, and a host of businesses came under the banner of “The George Calombaris Empire.” But a business built around celebrity is a vulnerable one, as Monday’s news proved, and George has long since ceded control of “his” empire.

Being in the restaurant business without retaining, or exercising control, can be a hot potato, as Calombaris’ fellow celebrity Manu Feildel discovered when he tried to open a Melbourne restaurant, Le Grande Cirque, in 2014. It lasted five minutes. And Australian diners have a fairly short attention span when it comes to restaurants run by titular celebrity chefs. Some big names, like Gordon Ramsay, have sailed these waters of token involvement, only to fail.

The popular consensus is that MAdE’s woes relate to the chef’s fall from grace. Are those woes because of dud numbers through the doors as a result of the golden boy losing his lustre, deserved or not?

Maybe it’s just another case of a restaurant group in trouble for a matrix of business reasons to do with costs exceeding revenues. One that just happens to have built itself around the star-power of Calombaris, the Melbourne chef who famously didn’t even open his VCE results because he’d already started an apprenticeship and was doing the one thing he’d wanted to do since childhood: cook.

Answers will trickle out in the weeks ahead as administrators pull apart the complex MAdE Establishment – a company of which Calombaris owns less than 20 per cent – and report to creditors. It may simply be another case of too big, too soon in a fickle retail business where labour and the infamously complex industrial relations framework it operates in can mean the difference between profit and loss very quickly.

Or will this go down as on the great fall-guy stories of all time? One in which the company screwed up – on a number of levels including the wages underpayment issue – but with such a recognisable celebrity figurehead to be flayed, it was too easy for the rank and file of the industry to pile on, with consumers following in lock-step.

Irresistible celebrity clickbait.

Personally, I doubt George Calombaris knew to the full extent or detail what was going on in head office with individual staff payments. He was out there, doing what he does. Television, endorsements, media commitments, books, celebrity gossip columns, spats at the soccer. Occasionally, even, cooking.

Not payroll.

But when it hit the fan, it was Calombaris who was flayed in public, not the other directors of MAdE. George was an easy and obvious target.

The accepted wisdom is that following the underpayments scandal diners stopped dining. This is certainly partly true. Yet insiders within MAdE tell The Australian that some branches of the business, such as Jimmy Grants, the souvlaki brand, and Yo Chi, a frozen yoghurt business MAdE acquired in 2018, are still trading well. That other factors are at play, which have nothing to do with Calombaris’ reputation damage and how that translated to numbers through the door.

Still, the company, having lived by the sword, has been doing its best to make sure the stab wounds didn’t prove fatal. MAdE has been de-Georgeing its businesses quickly, rebranding and reinventing four of its major restaurants in short succession, hoping to draw a line under the Calombaris association. It wasn’t a matter of too little too late; it was quite a lot, actually, but it was still too late anyway. None of the MAdE businesses opened their doors on Monday.

This fall of The House of George follows in the footsteps of another massive celebrity’s exit from Melbourne recently, that of Briton Heston Blumenthal whose Dinner restaurant at Melbourne’s Crown closed amid another staff underpayments scandal. The restaurant’s owner – a company ultimately owned by Heston Blumenthal – went into voluntary administration in December.

There have been a string of investigations by Fair Work Australia over the past two years alleging staff underpayments in the restaurant industry, many associated with chefs whose celebrity status has been good for business. They include Neil Perry and Guillaume Brahimi. Others include restaurateurs with huge reputations, such as Sydney’s Justin Hemmes.

On one side of the fence, Fair Work and the unions say the restaurant industry systematically exploits staff by not always paying for the full number of hours worked. On the other, the industry says the awards and penalty arrangements are overly complex and easy to get wrong, not allowing for the kind of flexibility required in a retail/service business when demand fluctuates considerably. That, in short, it’s too easy to make a mistake with staff payments.

Whatever the case, when it involves a business that has leveraged itself on celebrity and profile, grown fast dancing to the tune of Economies of Scale, the media interest gets rabid, because it’s no longer just a business story. When chefs like Calombaris or Adriano Zumbo get in bed with backers who just love that their figurehead is tabloid fodder and — even better — on television, it can quickly become a case of not just the butter being spread too thin.

For Melbourne chef-cum-restaurant entrepreneur George Calombaris, it’s been a case of the harder they come, the harder they fall. George and his backers at MAdE Establishment have been in rapid expansion mode for the past five years, a lot of it allied to the unlikely celebrity of a minor shareholder, a loveable Greek kid who has grown up on our television screens to become almost omnipresent since that first episode of MasterChef plucked him from relative obscurity in 2009.