Escapee Kevin Simmonds stumped by brutal ‘justice’ after recapture

A manhunt for two escapees took on a greater urgency after the fatal beating of a warder using weapons taken from a sports storeroom.

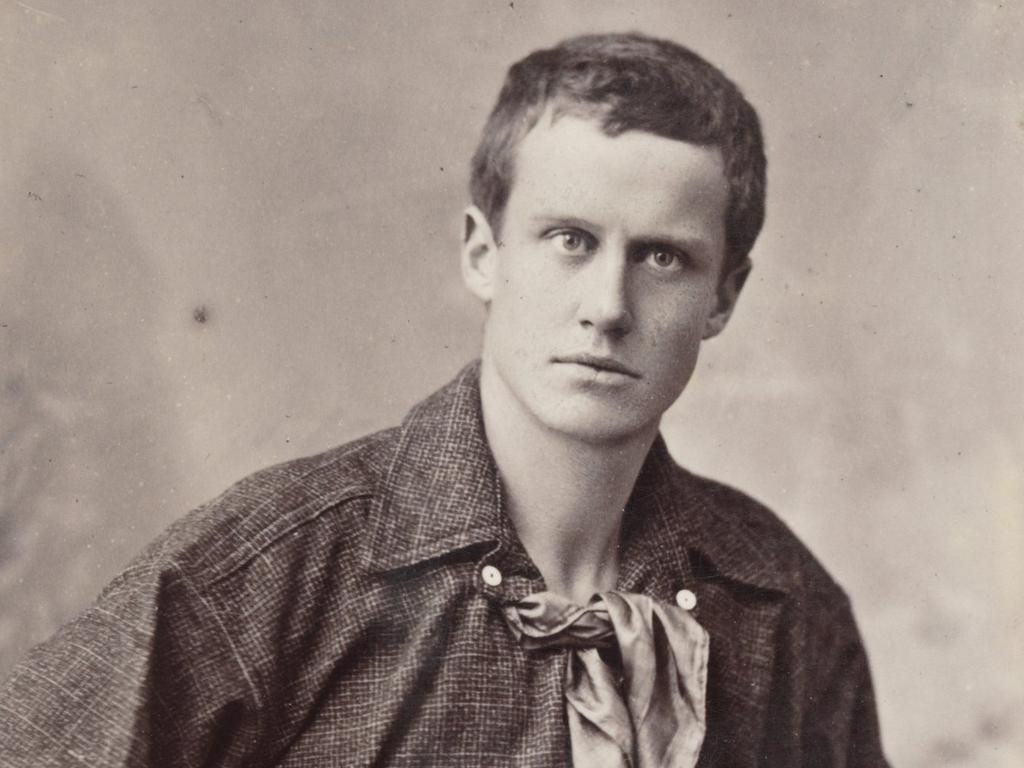

For 37 days in 1959, the whole of Australia hung on the names Kevin Simmonds and Leslie Newcombe, escapees from Long Bay Jail, where they had been sharing a cell after convictions for robbery and housebreaking. Young, bold, photogenic and seemingly a step ahead of their relentless pursuers, they brought the romance of Rufus Dawes into the television age, although it was irrevocably stained with blood. Part of the romance lay in the sheer simplicity of their methods. All they needed to escape from Long Bay on October 9, 1959 was a forged pass to gain admission to a courtyard, a workshop hammer to break a chapel door, their bare hands to prise slats from a ventilator shaft, and the fixity of purpose to relieve five protesting nurses of their car in the Prince Henry’s Hospital carpark.

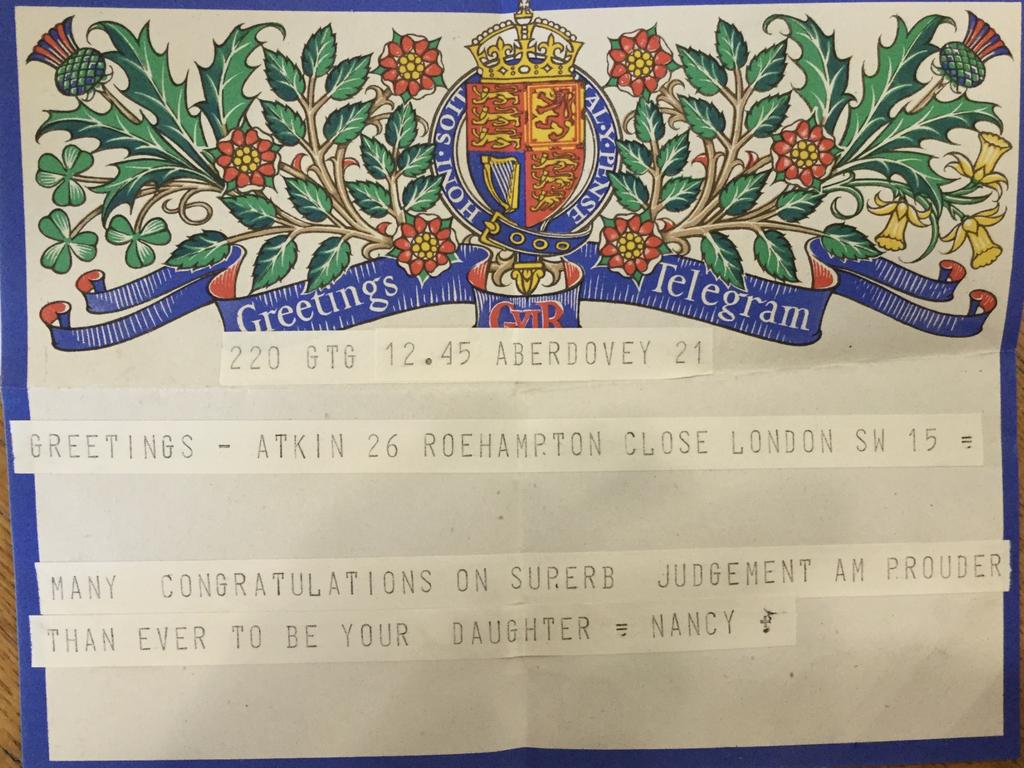

The pair made a base in the Pig Pavilion at the Sydney Showgrounds before heading, counterintuitively, for Emu Plains Prison Farm, which Newcombe, who had previously served time there, knew to be minimally guarded at night. Executing their plan to gather supplies and weapons, they took from a sports storeroom a baseball bat and this cricket stump, now in Sydney’s Justice & Police Museum.

Simmonds and Newcombe were disturbed, however, by a warder, 40-year-old Cecil Mills. Simmonds thought to bash him unconscious, but Mills would not fall, and the blows proved lethal. “He was still standing firmly on his feet,” Simmonds would tell a court. “I must have hit him too hard and too often.” The pair set off for Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park in Mills’ car, learning en route that they were wanted for murder. Simmonds and Newcombe were then separated in the act of robbing a delicatessen in Mona Vale. Figuring his confederate would return to the Showground, Newcombe went there. But when Simmonds did not reappear, Newcombe decided to make another run for Ku-ring-gai, only to be snagged in the police dragnet on Oxford Street.

In fact, Simmonds had slipped into the bush at French’s Forest, where he heard of Newcombe’s capture. He embarked for Ku-ring-gai anyway. There, fit and resourceful, he built a branch-covered bower over a stolen car, and started digging an adjacent pit in which to bury a stolen caravan. Simmonds was toiling at his pit when he was surprised by a park ranger and a boatshed employee. Though naked, he nimbly regained use of his pistol, tied the pair up and made off in their blue-grey Morris Oxford utility. He slipped a roadblock and a police motorcyclist, then foiled specialist tracker alsatians by fording the flooded Wallis Creek, although losing his revolver in doing so.

By now, the manhunt was all over newspaper, radio and television. In his unsparing prison memoir, Intractable (2006), Bernie Matthews describes the atmosphere in Simmonds’ old home town of Griffith while the local boy was on the run: “Simmo’s mother lived in an old house near the canal. We listened to the oldies tell stories of how Kevin was really a good bloke who had just gone off the rails …. Everybody was hoping Simmo would get away.” Following events was Simmonds himself, not displeased by his celebrity.

The Hunter, appropriately, was the scene of the denouement, which involved at least 500 police, 300 further volunteer searchers and a valiant milkman, who saw Simmonds hot-wiring a car before dawn in Kurri Kurri and gave chase in his milk float. As police converged, Simmonds emerged arms raised from a cluster of ironbarks, starving, exhausted, filthy and lousy with leeches and ticks. The conclusion was strangely sporting. At Wyong police station, Simmonds scarfed “nine big sandwiches, a quarter of a pound of chocolate, an apple and six biscuits”, telling police that had he been as well fed as they, he’d never have been caught. In return, he did not object to their treating him like a trophy, posing with his pursuers, including the canines, Chrissie and Dawn. The law was less enamoured. Simmonds and Newcombe pleaded not guilty to murder, but when a jury found them guilty of manslaughter on March 18, 1960, the judge imposed life sentences, deprecating the “maudlin sympathy” they had provoked. And though Newcombe’s sentence was reduced on appeal, Simmonds’ was not.

Grafton Gaol was a notoriously brutal gulag. There was no sports storeroom here. Daily exercise was limited to 20 minutes of marching in cell order back and forth across the yard, hats on, coats buttoned, eyes downward. Nor were there newspapers, radio or television, although Simmonds was already well enough known. As the killer of a prison officer, he was singled out for specially sustained and sadistic violence and humiliation. He deteriorated, recalled his sister, Jan, “into a physical and nervous wreck, seemingly without the ability or the will to stop himself”.

On November 4, 1966, the day after Simmonds learned of the failure of his application for a transfer, he was found hanged in his cell. A detective called it “the most determined suicide attempt” he had ever seen, giving rise to speculation of murder.

A legend outlived him. He inspired a song, an episode of Homicide and numerous tellings of his escape, including in Newcombe’s Inside Out (1979). So did fact: Simmonds’ death contributed to a groundswell of concern about conditions in prisons in NSW, the Nagle Royal Commission (1976-78) eventually describing Grafton’s regime of “extreme violence” and “mindless beatings” as “at once rigid, monotonous and designed to strip prisoners of all vestiges of individuality”. The last Australian hanged, Ronald Ryan, famously paid with his life for a bungled prison escape. Kevin Simmonds fits the bill also. As sister Jan wrote in her book, For Simmo (1980): “Regardless of whether my brother died by his own hand or someone else’s, the prison system was responsible as surely as if a judge had ordered the execution.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout