English tourist Charles Lawrence the ‘father of Australian cricket’

Cricket breeds huge characters, none more so than English sporting entrepreneur Charles Lawrence.

On June 10 last year, male and female indigenous teams constituted by Cricket Australia met at Lord’s with the visiting Australian cricket team.

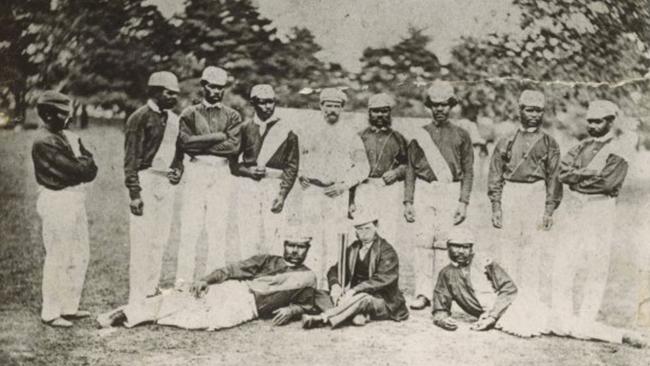

The former were marking the sesquicentenary of the famous Aboriginal XI, which improbably toured England in 1868. The latter were, effectively, their hosts.

To commemorate the encounter, photographs were taken, including re-creations of a team shot taken 150 years before, with a guest in the middle of the back row. Tim Paine was more than an ornamental presence: he was standing in for the pioneering team’s only non-indigenous member, captain Charles Lawrence.

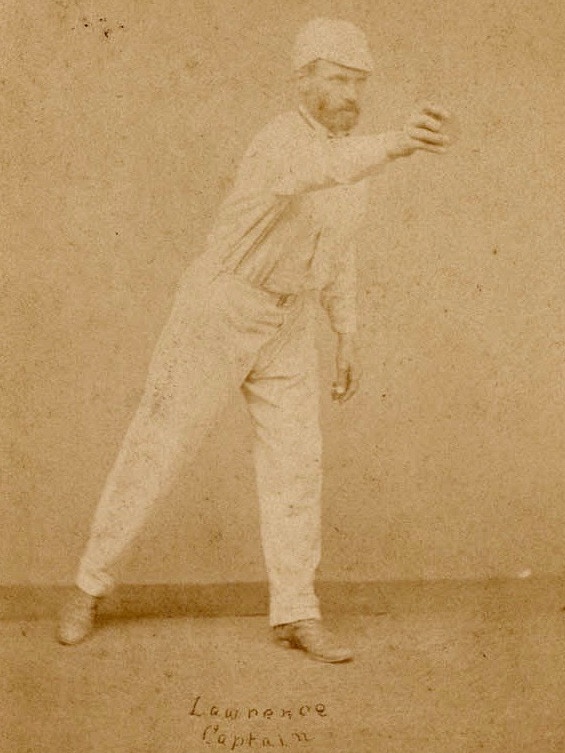

The 39-year-old Englishman Lawrence was a figure almost as unlikely as the team he led. He had come to the Antipodes in the first English team to visit these shores, led by HH Stephenson in 1861-62 — and stayed.

In other words, uniquely, he was part of Australia’s first inbound and outbound cricket tours.

On his death in December 1916, Lawrence was feted by obituarists as “the father of Australian cricket”. Yet the years have not been kind to him.

The Aboriginal team exerts a continuing fascination, reflected in a full-scale museum at Harrow in Victoria and Geoffrey Atherden’s forthcoming Sydney Festival play Black Cockatoo. But, for its captain, history has struggled to find a place.

Lawrence was born in London’s East End in December 1828 and educated in a village school in the rural speck of Merton. The family worked in textiles: father John was a colour maker; Charles became a print cutter. The boy’s aspirations, however, were simple.

“I had a greater love for cricket than for any other amusement,” he recalled in fragmentary handwritten reminiscences, “and from early morn to late at night I was to be seen with bat and ball.”

In June 1842, to see his batting idol Fuller Pilch, Lawrence walked 20km to Lord’s, asking directions because he knew no more than that the ground was “somewhere in the London district”.

Pilch came to bat, Lawrence remembered, amid a frenzy of enthusiasm: “But the noise had barely ceased when I heard something say ‘oh he’s bowled first ball’ which was indeed the case … My heart was in my boots and I commenced to cry …”

What upset Lawrence more, however, was work, which he detested, threatening to run away to sea if he could not give it up — a threat his father took seriously.

With family consent, Lawrence first established a reputation in Scotland as a fast round-arm bowler, lean and lightly framed.

He then took a young bride, Anne, to Dublin, where they had three children.

Those years, mainly at Phoenix CC, were probably Lawrence’s playing peak. He was a cricket tutor to the sons of two lord lieutenants, the earls of Carlisle and Eglinton, and laid out a substantial cricket ground at the Vice-Regal Lodge, where he achieved the feat of a half-century and 10 wickets in an 1856 match against the Gentlemen of England.

Representing Ireland against Marylebone CC at Lord’s two years later Lawrence took 12 for 57.

Lawrence was less lucky in business. He went broke as a tobacconist; he lost money buying and selling a racquets court; he misspent an inheritance; his benefit matches were ruined by weather. He probably joined Stephenson’s pioneering professional XI as much from need as desire, though the long journey on the steamer Great Britain might have satisfied the sailor in him.

The visitors were challenged less by their opponents on the six-month tour than by the extraordinary distances traversed and the hostility of the climate — so hot, Lawrence’s teammate William Caffyn said, “as to fetch the skin off our faces”.

They were, nonetheless, impressed by the fervour of the colonial reception, so great that the team needed to practise in secret rather than risk being stampeded.

It must have dawned on Lawrence at some stage that his future lay here, for he remained behind when the team sailed at the end of March 1862. And it was announced three months later that he had been retained by Sydney’s Albert Cricket Club as a coach.

There had never been such a role in Australia and Lawrence rapidly became a big deal in the colonial cricket community.

At 353 George Street he established the “NSW Cricketing Depot”, which imported sports equipment from England and offered “all information connected with the game of cricket”.

It also provided a meeting place for the fledgling NSW Cricket Association, where members could partake of a range of cigars and enjoy a game of billiards.

Appointed captain of NSW, Lawrence took a match-winning 14 for 73 against Victoria in his first game, still a record, and proved himself something of an innovator by dispensing with a wicketkeeper.

In April 1864, against the second English team to visit Australia, he led a NSW squad to victory, taking 10 for 90.

Where his contribution was greatest, however, was as a coach. Caffyn, who had come back to Australia and would end up staying, was struck by the local improvement, with which he credited his former teammate: “I must take this opportunity to speak of the good work done towards the development of Australia cricket by Charles Lawrence, who by his perseverance, energy and ability did a great deal towards raising of the game to its present high standard.”

Improved standards made cricket a game worth watching, and paying for. In October 1864, Albert CC opened Sydney’s first enclosed ground, in Redfern. It’s no fluke four of Australia’s first 15 Test cricketers would later have Albert CC pedigrees.

Lawrence had by now been joined by his wife and children, and looked to a longer-term career. In October 1865 he became licensee of the Pier Hotel on the Corso at Manly Beach.

But, after a year, tragedy struck. Anne died from the after-effects of childbirth and five days later so did the five-week-old infant.

Shortly after Christmas 1866, The Sydney Morning Herald reported the Pier’s licence, stock and furniture was for sale due to the owner’s “severe domestic affliction”. While Lawrence was in this state of flux he also hosted some extraordinary visitors.

On stations in Victoria’s Western District, cricket had achieved a huge popularity among indigenous workers, who quickly achieved superiority to their white overseers. So impressed was young pastoralist William Hayman he sent their photographs to the Melbourne Cricket Club.

The club consented to a game on the MC, and sent star all-rounder Tom Wills to coach the indigenous team at the Haymans’ Lake Wallace station.

Ten thousand spectators attended the match on Boxing Day 1866 developing a strong sentimental liking for the visitors, who not only played good cricket but also enriched their spectacle with athletic displays and native skills.

One onlooker, William Gurnett, was a recent arrival from Kent and an Albert CC member who lured Hayman into the idea of a 12-month cricket tour, starting in Victoria, working its way through NSW and leading on to England.

Gurnett was a crook, and the venture started going wrong almost immediately, laced with unfulfilled promises and bouncing cheques. When the team played against Albert CC, Gurnett tried turning the tables by having Wills and Hayman arrested for breach of contract. It was with Gurnett the law finally caught up: he served jail time for fraud and forgery.

While the team was stranded at the Pier members established a rapport with Lawrence, who followed them back to Lake Wallace with the idea of reviving the tour. It was he who designed their garish uniform of white flannel trousers and linen collars, red shirts and blue sashes, and who encouraged them to practice their tribal skills of boomerang and spear throwing “which pleased them very much and they soon became proficient and willing to do anything that I wanted them to learn”.

It was Lawrence who led a dozen of them from Edenhope on a bullock-drawn wagon on September 16, 1867. Commuting to and from England in wool clippers, they would not return for more than 18 months. The team’s feats are legion and legend, names such as Unaarrimin (Johnny Mullagh) and Yellanach (Johnny Cuzens) echoing euphoniously down the ages. Less well understood is how they and Lawrence related so improbably but effectively.

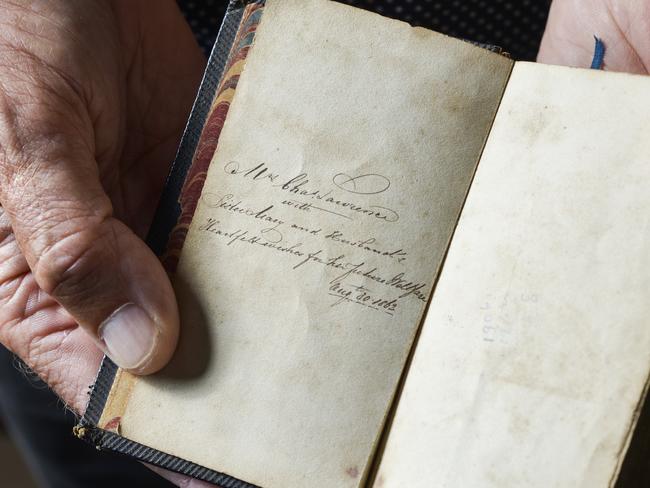

One medium seems to have been Christianity: Lawrence’s great-great-grandson Ian Friend still has the Bible from which his ancestor read aloud to his charges. Lawrence was also intensely leery of the influence of alcohol, which left his players “quite helpless”.

His attitude seems to have been fond and benevolent. When the players succumbed to the lure of hospitality, said Lawrence, “like children they would promise to be better” and “I always forgave them” because they “would do anything to please me”. There was also, perhaps, some mutual respect, for Lawrence remained a fine cricketer even in his 40th year.

Unaarrimin, with 1698 runs at 24 and 245 wickets at 10, was the team’s outstanding performer but Lawrence was barely his inferior, with 1156 runs at 20.2 and 250 wickets at 12: without him, it’s unlikely the team would have been so seriously competitive.

He even joined in their displays of athletic and hunting prowess, balancing on the blade of his bat balls thrown at him in quick succession by his players.

Perhaps no touring captain, meanwhile, has faced such challenges as guiding a team of dark-skinned men through pale-faced England. Some of these were comical, such as when Lawrence took his charges to a public bath and patrons objected in the belief they were filthy miners.

At the same time, no touring captain has had to deal with the sorrow of the death of a player.

That was Bripumyarrumin (King Cole), who died of tuberculosis in Guy’s Hospital on June 24, 1868. In Friend’s collection is doggerel Lawrence recited over the cricketer’s grave in Victoria Park Cemetery, describing Bripumyarrumin as “run out for nought in the race of his life”.

It also contained a poignant prophecy: “But smile gallant fellows not few are the friends / Who would soften the place of his pillow / It may be our children will garland his grave / ’Ere you have gone over the billow.”

Last year’s indigenous XIs visited Victoria Park, where a eucalyptus grows in Bripumyarrumin’s memory.

Was the tour a success? The players toiled hard, Lawrence not least, through 122 days of cricket. The accounts suggest a profit; anecdote suggests a loss.

Whatever the case, their captain did not grow rich: instead, Lawrence began a 24-year career with the NSW Railways in Newcastle. He married again and became a father thrice more, though two of the children died in infancy.

In August 1892, white-bearded but spry, he was again engaged as a coach, this time by the Melbourne Cricket Club, on £2/10 a week. Among Lawrence’s tasks was to grade juniors on a scale from “very good” to “indifferent”. His eye must have been keen: a protege, Vernon Ransford, made a dashing Ashes hundred at Lord’s in 1909.

The times had moved on. In 1898 the MCC voted Lawrence a benefit match between “an eleven of Victoria” and “15 of his pupils”, but the Easter crowd was small and there remained few contemporaries left to share it with.

In his final year, widowed, he wrote the club requesting a testimonial, describing himself as “not in affluent circumstances” but still proud to have been “one of the first to represent English cricketers in Australia and the first to represent Australian cricketers in England”. It met without success.

Last month Cricket Australia affixed on Lawrence’s grave in Brighton Cemetery a plaque enumerating his achievements. And, unless he goes on to play for England, Paine will not rival them.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout