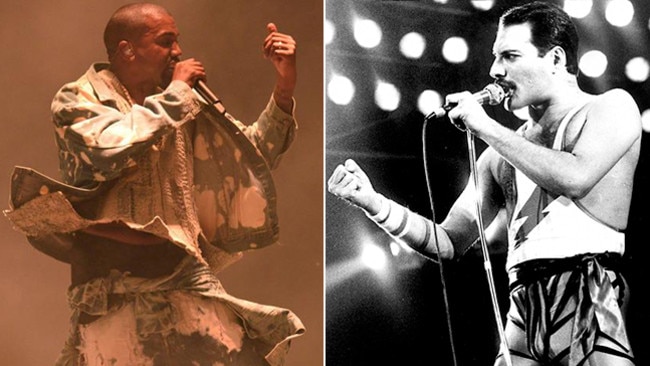

Bohemian Rhapsody turns 40; even Kanye West covered it at Glastonbury

Bohemian Rhapsody turns 40 this year, and now even Kanye West is ‘singing’ it. What makes the song such a survivor?

Going to a gig soon? Better brush up on your Bohemian Rhapsody lyrics then.

These days, everyone from Pink to Panic at the Disco and Brisbane band Ball Park Music is covering the damn thing at gigs, and turning the Marshall stacks down low for the crowd to join in. If you really want to get swept up in the Zeitgeist, you’d better know how to phrase, “Beelzebub has a devil put aside for me,” even if you don’t know what the hell it means.

There are a few reasons why Bohemian Rhapsody continues to survive, and at times acquire stadium status.

First, it is one of the most singable hits in pop history. Freddie Mercury, who wrote and sang the tune with his band Queen in 1975, had a four-octave range, much of which he used in the song, but the best bits are still accessible even to people limited to a couple of notes either side of middle C. “Mama, just killed a man / Put a gun against his head / Pulled my trigger, now he’s dead,” is almost impossible to butcher. Even the Great Gonzo pulled it off when the Muppets had a crack at the tune in 2009. But whatever your range, you still have to sing it, which was Kanye West’s big mistake at Glastonbury last weekend.

Second, the song is celebrating its 40th anniversary this year. If nothing else, it is a relic from a time when pop music was pretentiously experimental, at a time when a bit of pretension and experimentation wouldn’t go astray.

The song’s potential as a stadium hit became obvious at a Green Day concert in London in June 2013. The PA played the song to the crowd as it waited for the band to come on stage; mass spontaneous karaoke ensued, and the subsequent Youtube video has since topped a couple of million. Other performers took note, and pencilled the tune into their playlists.

It’s important to point out that the crowd at that concert consisted of people not born when the song was released. Hell, most of them weren’t born until after Mercury died, in 1991.

The song is so deeply ingrained in our culture that Grant Denyer, back when he was the weatherman on Sunrise, once said of a forecast storm: “Thunderbolt and lightning, very very frightening.” Suddenly, to me at least, the weather rattling my window didn’t seem so scary.

That’s because Bohemian Rhapsody is a camp, rock-opera parody about challenges far more intense than a bit of wind and rain. Killing people, disappointing your mama, fatalism, death, nihilism and the need to “get right outta here” are all covered within the song’s six distinct sections over six glorious minutes.

But, beyond operatic parody, what does it really mean? Is there anything more than a cheap lament in “I don’t wanna die”? Is the visceral guitar riff that accompanies, “So you think you can stone me and spit in my eye” tapping into anything more than a head rush? What depth of despair is Mercury referring to when he sings, “I sometimes wish I’d never been born at all”?

Not even Mercury would, or could, answer any of those questions. “It’s one of those songs which has such a fantasy feel about it,” he once said. “I think people should just listen to it, think about it, and then make up their own minds as to what it says to them.”

In that way, it’s an amusing, brilliantly performed ode to nothing. Mercury himself embodied this. He was born in Tanzania into a Parsi family, and moved to England as a teenager. He was a camp performer, but gave little else about himself away to his legions of mostly straight fans.

Some time later, rumours of the band’s sybaritic lifestyle became folklore. “According to their drummer Roger Taylor, Queen ‘revelled in decadence’ for 20 years,” Iain Shedden wrote in The Australian in 2002. “While dwarves dishing out cocaine from silver salvers on their heads remains an unconfirmed element of their post-gig relaxation, they most definitely liked a good party.”

Mercury spent several years denying he was HIV-positive before dying of Aids in 1991, aged 45.

He would have been pleased, of course, to see the song become an anthem to new generations, but the 40th anniversary might wind up being overkill. Already, the band’s surviving members have approved a Bohemian Rhapsody beer.

If the tune survives beyond its current popularity, it will be because it has an in-built defence against pop’s inevitable self-destructive cycle. A song or band becomes a hit for reasons nobody quite understands, then, a few years or decades later, a new generation of fans jump on it, but this time assuming a slightly ironic posture, as if they dig it despite its original ephemerality. With each new wave, the cycles become shorter, the new fans fewer, and the irony less ironic, until the song or band disappears altogether.

But you can’t be ironic about a parody, especially one with such a liberating conclusion, repeatedly sung against light piano arpeggios, as, “Nothing really matters”. Bohemian Rhapsody works, whether you understand it or not, because it takes the piss out of itself before anybody else can.