Being a spook isn’t easy for Bond or Maxwell Smart

Working closely with people in the intelligence game, it seems everyone is forced to play a role.

We were on a military aircraft on descent into a Middle Eastern country during a time of war and a senior intelligence officer was keen to impress on me an important point before we landed. “You remember Susan (not her real name) who used to liaise with your ministerial office in Canberra?”

I nodded.

“You are likely to see her when we get to the embassy, but her name now is Naomi (not her real name or her real pseudonym) and you should pretend you have never met her before. So just make sure you don’t refer to any of that previous work.”

Sure enough, an hour or so later, I pretended to meet Naomi for the first time, without betraying any hint that I knew anything about her role. Truth be told, it was not easy to feign indifference because I was intrigued – it is not every day you meet a smart, young, undercover espionage agent in a combat zone, whatever her name.

There was much that fascinated me over the years I spent as media adviser then chief of staff to the foreign minister. In the world of diplomacy, consular affairs, politics and media even what passed for an uneventful day was stimulating enough.

Still, the unexpected responsibility of dealing with spies of various kinds never lost its edge. It was a serious business, often related to threats at home and abroad.

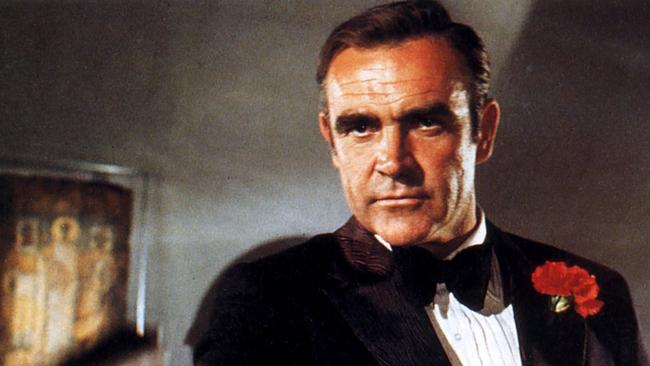

Countering the efforts of foreign spies was something that became second nature – awareness about the vulnerability of phone calls to interception, suspicions about personal encounters, and keeping documents secure. All the same, there were times when these secrets and role-playing led to amusing escapades more redolent of Get Smart than James Bond.

When travelling overseas, important conversations were sometimes delayed until they could be held in safe rooms in the embassies.

But I recall one night in Tehran when senior intelligence and diplomatic officials needed to share some information, so they huddled together in the middle of a hotel room, and we cranked up the stereo to 11 – it was like whispering sweet nothings on a dancefloor.

Another time back in Australia one of our agencies needed to pass some documents to me for secure passage back to Canberra, and I was told an agent would recognise me in the airport lounge to hand them over. When I entered the Qantas lounge, there must have been a hundred or more blokes in suits spread around the room but there was something about one of them that attracted my attention.

He was in an armchair, reading, with a briefcase tight against his legs. I approached and asked if he was looking for me. Sure enough, I had picked the right man. Presumably, he reappraised his spycraft afterwards.

Wrapping up another trip to the Middle East, I was booked on the same flight back to Sydney as a senior intelligence agency operative who had booked a car to the airport and offered to give me a lift. When it was time to depart there was much consternation in the hotel foyer over an apparently bungled booking and a missing vehicle – until our spy chief realised the waiting car and driver were his, just booked under another identity.

Most spies, of course, do not – must not – reveal themselves, even to their close colleagues. We might know them as bureaucrats or government officials with dull-sounding careers, oblivious to their clandestine roles.

On a long drive to an intelligence training facility, one of the nation’s most senior officials confided in me about the personal difficulties of leading this double life. There was the frustration of friends and family thinking he had a tedious public service job in some decidedly unsexy area of government that involved at least some level of international negotiation to provide reasonable cover.

But more testing was the growing awareness and questioning from his teenage children, who had become suspicious about his work and travel patterns, correctly realising how they did not really add up. It was an extraordinary insight into the torment of a daily life full of diversions and subterfuge, not just at work, but by necessity in his private life as well.

For the good of the nation these people live a double life, where reality is denied and a false narrative of white lies is created, even for their loved ones. These agents need to lie, and convincingly live that lie, for the best of reasons. It must be an uncomfortable, if enlivening, existence.

Not long after I was promoted to head up the foreign minister’s office, some intel was brought to my attention. It was reported that diplomats in a foreign capital had discussed my appointment and issued instructions for their embassy to find out more about me.

Sure enough, within days, an attractive political counsellor from that nation’s Canberra embassy invited me to lunch. She laughed at all of my jokes.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout