Why trying to appeal to younger voters (at the expense of older ones) isn’t the answer

The message this election is that the era of aged power is over, the boomers are busted and the new voting power is with the young. There’s just one problem with this narrative: it’s wrong.

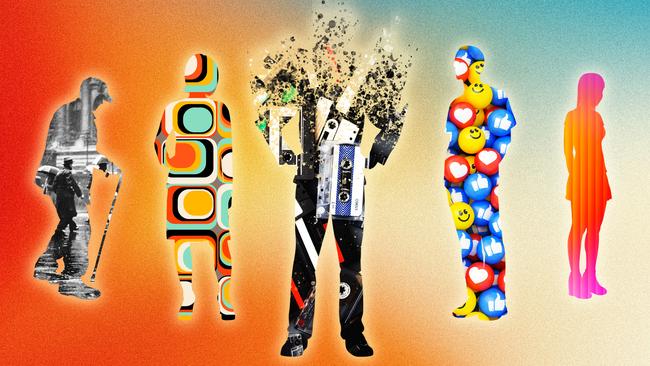

There’s a new political story being told in the 2025 election with a fundamental, profound and unprecedented message: the era of aged power is over, the boomers are busted and the new voting power is with the young.

The changing demographics are being hailed in grand geological terms such as “tectonic shifts” and “youthquake”.

The cry is that we are in a new political age and the voting power of the young – Generation Z (aged 13 to 28) and millennials or Gen Y (29 to 44) – is here with “young voters outnumbering the older cohorts for the first time”.

The idea that Gen Z and millennials will outnumber baby boomers (61-78) for the first time is being used to appeal to political parties to shift policy, to point to new voting blocs and to adopt new campaign strategies and techniques to reach the younger generations that don’t use television, radio or newspapers.

Anthony Albanese has invited influencers on to his campaign, given an interview to media personality Abbie Chatfield for her It’s A Lot podcast and posed with dog-cradling friends on social media.

Peter Dutton did an interview on the Diving Deep podcast with Sam Fricker, an Olympic diver turned social media star who has 5.8 million YouTube subscribers and two million TikTok followers.

Parallels are being drawn with the US presidential election techniques of Kamala Harris and Donald Trump, who reached out to young voters on social media. Trump appeared on The Joe Rogan Experience – with a keen eye on the young male vote – and Harris spoke to Alex Cooper on the Call Her Daddy podcast.

The argument is that this tectonic shift away from older Australians means political leaders need not expect the ballot box pain meted out to Bill Shorten as opposition leader in 2019 for proposing changes to negative gearing tax breaks on housing investment, hits on high-end superannuation schemes and capital gains tax. These cost Shorten dearly with older voters, especially self-funded retirees.

It’s a narrative and an agenda that suits campaigns directed at the young inner-city areas and offers rent relief, increased living allowances and lower education costs.

The Prime Minister has cut $3bn in student HECS debt, offered fee-free TAFE, increased rent assistance and put up billions for social housing. But he also has ruled out changes to negative gearing investment rules or capital gains tax, although Labor has taxed earnings for superannuation balances above $3m.

The Greens are appealing to this new younger voting bloc by seeking rent freezes, more social housing and the cutting of tax concessions for housing investors.

This week Greens leader Adam Bandt said he would be astounded if Albanese didn’t deal with the Greens in a minority government and listed help for young renters and taking action against negative gearing and capital gains tax as Greens priorities for young people.

Albanese insisted he’d do no deals with the Greens to form a minority government and continued to reassure investors he had no plans to change negative gearing.

The Opposition Leader, who has strong support among voters over 60, consistently outpolling the ALP in this age group in Newspoll surveys, has been appealing directly to younger people, who he says are being denied the great Australian dream of home ownership, by proposing early access to their super to buy a house.

But there is a problem with the new narrative on the majority voting power of younger Australians: it’s wrong. There is a con at the heart of this growing assumption of majority power for young voters. Like all confidence tricks, there is some truth to provide credibility but it’s still a deception designed to skew policy and promises while providing legitimacy and voting authority to certain agendas.

All the calculations and commentary have omitted an entire older generation, Generation X (45 to 60), the benighted missing generation, caught between the baby boomers and the millennials.

Gen X is still caring for children, albeit young adult ones, paying big mortgages, suffering marriage breakdowns and facing the challenge of matching their parents’ ability to own their own home and retire comfortably.

Despite all of this, these voters have been written out of the latest electoral calculations.

This week, Monash University’s Centre for Youth Policy and Education Practice released a youth study on the concerns of young people ranging from mental health services and climate change to housing shortages.

The announcement said: “A ‘youthquake’ is set to shape up the 2025 federal election as millennial and Gen Z voters outnumber their older counterparts at the polls for the first time.”

The claim that for the first time young voters in the millennial and Gen Z cohorts will outnumber older cohorts has been bandied about since 2024 and has grown and intensified recently in the media, among researchers, marketers, pollsters and politicians. It has been used to urge young people to register to vote on May 3 and exercise their new political power.

The basis of this new narrative is the fact the combined number of voters in the millennial and Gen Z cohorts is now greater than the number of baby boomers registered to vote in a federal election.

The Australian Electoral Commission’s elector count of age groups shows the total number of registered Gen Z voters, those born between 1997 and 2007, now aged 18 to 29, and millennial voters, those born between 1981 and 1996, now aged 30 to 45, is 7,718,208.

The total number of voters aged over 70, which the AEC records as one group, is now 5,871,342. This figure is made up of baby boomer voters, those born between 1946 and 1964, now aged between 60 and 80, and heroic generation voters, those born between 1928 and 1945 and aged between 80 and 104. The so-called heroic or silent generation, as they are known in the US, includes many who lived through the Depression, World War II and every war, recession, disaster and pandemic since.

This is the declining generation of Arthur Leggett, who had been an Australian soldier taken prisoner by the Germans during World War II and who died aged 106 earlier this week. This generation is concerned with aged care, pensions, superannuation, health services and their children and grandchildren, as well as all the same concerns as everyone else.

Their inclusion by the AEC in the cohort with the baby boomers doesn’t alter the balance and there is a clear majority for the two younger cohorts – Gen Z and millennials – over the two older cohorts, heroic and boomers.

In February, Flinders University lecturer in government Intifar Chowdhury described the change as one that “massively shifts the centre of gravity of Australian politics” and would “definitely” shape the election.

But here’s the rub: there is an entire generation that has been arbitrarily left out of the equation – Generation X, those born between 1965 and 1980, now aged 45 to 60.

It’s understandable that Generation Alpha, born between 2010 and 2024, is not included in any of the voting calculations because, with the oldest at 14, they don’t get to vote. But to exclude Gen X is a statistical pea-and-thimble trick.

There are 4,350,268 Gen X voters on the electoral roll and when added to the other older cohort the total is 10,221,610 voters over age 45 out of a total 17,946,377 voters.

That is not just more older voters than younger voters but a clear majority of all voters.

This doesn’t mean politicians and policy shouldn’t be directed at the younger cohorts but neither does it mean the issues affecting older Australians can be neglected or dismissed because there has been a “youthquake”.

Monash’s Centre for Youth Policy and Education Practice director Lucas Walsh says his research tended to focus on the 15 to 30 age group and seeing greater policy attention to younger generations is welcome.

“But with Gen X making up around a fifth of the population share, this generational cohort seems to be missing from policy discussions,” he tells Inquirer.

Declaring “full disclosure”, Walsh says he “was born in the period popularly linked to Gen X, who has lived through a recession, the GFC and pandemic, as well as major house price increases, climate change, the introduction of HECs and eye-watering childcare prices”. “But I don’t see my generation clearly in current policy debates,” he says.

John Curtin Research Centre executive director Nick Dyrenfurth tells Inquirer that Generation X is the “missing piece of the jigsaw” in this election campaign with its emphasis on younger voters.

He says part of the political problem for parties in dealing with Gen X is that it tends to be internally divided between those who have experience of blue-collar job losses in the recession, especially in Victoria, and those who were born after this time. This is a problem for Labor.

Australian National University marketing lecturer and author Andrew Hughes, who has been following the commentary on the claims about younger voter dominance, says there is no doubt Generation X is the missing part of the equation. He tells Inquirer he believes Labor has “fallen into a trap” in looking closely at the younger cohort and not offering Gen X any aspirational policies.

“Neither side has really addressed the aspirations of this group who want to be able to match their parents in home ownership, to make money and have a secure and comfortable retirement,” he says.

In key marginal seats the pattern is the same.

In the NSW south coast seat of Gilmore, there are 128,000 registered voters and the older cohorts outnumber the younger cohorts three to one: 95,000 to 33,000.

Other Labor marginal NSW seats, Bennelong, Robertson and Paterson, all have more older than younger voters.

Of course, just because someone is older doesn’t mean they are going to vote conservatively, but they do tend to vote more along party lines and against proposals that threaten their superannuation, retirement, pension, home ownership, a comfortable life and the ability to pass on some of their life’s work to their children.

Even the Greens realise there has been a greying of the Greens voter, a sort of eucalyptus Green, because the youngest voters who historically voted the Australian father of the Greens, Bob Brown, into the Senate in 1996 are celebrating their 50th birthday – well into Generation X and only 10 years younger than the youngest boomers.

This goes to prove that none of the generations is homogenous or easily defined in political terms, so that even deliberately targeted campaigns, particularly for the younger voters, won’t guarantee a result, especially for the traditional parties.

As Dyrenfurth says, the millennials and Generation Z voters have little faith in governments acting on their concerns and some want to smash the system.

He warns: “If the mainstream left fails to deliver material change, the right will exploit frustration, as will the Greens. The ALP was born out of and sustained by working-class grievances with the establishment and righting injustice. It must channel this sentiment today or young Australians will seek answers elsewhere.”

But trying to appeal to younger voters at the expense of older voters, particularly by completely dismissing one cohort, is not a viable answer for either of the major parties.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout