Who controls Eurasia controls the world

The combined area of Europe and Asia will be the decisive geopolitical theatre in coming years.

Australians sees themselves as a peace-loving people. Far from distant troubles, Australia is not surrounded by enemies. Geographical isolation is seen as a source of security. Strategy and defence are not top of mind in national conversations. Australian politics is domestically focused. International issues are seen as intrusions into discussions about living standards, government services and entitlements.

The Australian sense of war is commemorative and mournful, built on the Anzac narrative, in which there is a strong streak of revulsion against senseless slaughter. True, long-term cultural and demographic shifts are seeing some faraway conflicts being increasingly played into Australia’s politics and society.

We can see this in the long wake of the heinous attack by Hamas on Israel on October 7 last year. However, we cannot hear the guns from our quiet and secure land.

Our instinct for peace does not make much sense to those who have to bear the consequences of not fighting – namely, subjugation and, in some cases, annihilation. For those who lack Australia’s blessings, a more brutally instrumental view of war has to be taken. However, are Ukrainians or Israelis, as the victims of aggression, any less peace-loving than Australians? When Australia itself was attacked in 1942 by Imperial Japan, there were no calls for an early peace or for the “de-escalation” of conflict. The right to defend oneself necessarily includes the right to wage war until the will of a dangerous enemy has been broken, so that a durable peace can be established.

There is no scientific basis for thinking that Australians are more peace-loving than anyone else. Cultural ideas emerge from material conditions – which include geography, resources and the proximity of adversaries.

By the time of Federation in 1901, conditions had shaped a distinctive Australian ideology. In a book about Australia’s sense of itself, A Sheltered Land (1994), French scholar Xavier Pons analysed how the isolation of a continent, girt by protective seas, generated in the Australian people a cultural valorisation of safe solitude in a wide, empty land.

Living in a sheltered land suited Australians who, at the time, saw themselves as being embarked on a great social experiment – namely, the building of a peaceful, prosperous and equitable society, far from historical antagonisms and constraints.

There were security anxieties, especially regarding Asia, but it was assumed that the empire would always afford protection. Such thinking was naive. As Australia was being constituted as a nation on its own continent, the struggle for mastery in Europe – to use the phrase made famous by historian AJP Taylor – was moving towards confrontation, and eventually war.

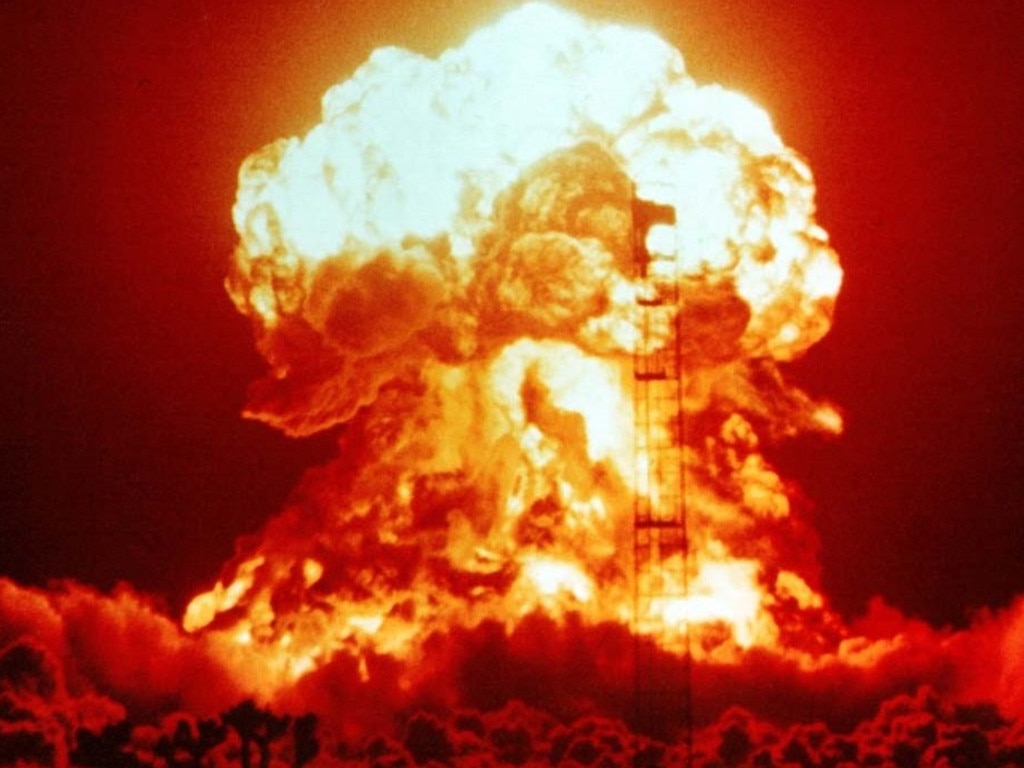

Since the mid-19th century, the great powers of Europe had been vying for mastery in that continent, in an age when Europe was at the centre of the world. After 1890, Imperial Germany was bent on attaining supremacy. WWI was the catastrophic playing out of that struggle on the battlefield.

Australia went to war as a dutiful member of the British Empire. The lens, however, through which we view WWI is wrong. We commemorate the dead and honour their sacrifice (as we should) while being repulsed by the “senselessness of war”. This dishonours the dead and their sacrifice. They died because there was no better alternative in a great geopolitical struggle. The consequences of yielding to Imperial Germany and its allies would have been worse than fighting to the bloody, horrible end.

In 1918, Australia played its most crucial role in world history by making the critical difference on the battlefield. On August 8, 1918, Australian troops at Amiens were in the forefront of inflicting on the German Army its “Black Day” from which it would not recover. With the German defences breached and US troops pouring into Europe, the outcome was settled. Imperial Germany was stopped from becoming the hegemonic power in Europe, at a time when Europe dominated the world.

Thereafter, the geopolitical canvas was broadened. Thus began the struggle for mastery in Eurasia, involving the great European powers, including Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy in the 1930s, as well as Soviet Russia, Imperial Japan and nationalist China. The US had announced its arrival in 1917 as the great “offshore” power, but to become the hegemonic arbiter that could shape the destiny of Eurasia from a distance it had to translate its stupendous economic power into military might. After the end of the war, it chose not to do so. It also opted out of joining the League of Nations.

Across the period 1931-41, with the US withdrawn into its hemispheric citadel and protected by two great oceans, Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy and Imperial Japan struck in the first great struggle for mastery in Eurasia. The weary empires of Britain and France could not hold the tide. Soviet Russia hedged until it was attacked by Nazi Germany in June 1941, and the US stood back, with a massive economy and a small military, until it was attacked by Imperial Japan in December 1941.

Australia again went to war as a dutiful member of empire. When Imperial Japan struck south in 1941-42, Australia and the US rallied in defending a perimeter around the farthest extent of the Japanese advance. While venerated as a symbol of supposed Australian independence, the Battle of Kokoda was in fact an action fought in the farthest corner of the wartime struggle for mastery in Eurasia, at the point where Imperial Japan was seeking to fix its southeastern-most maritime perimeter in Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands.

While we recognise how important the fighting was for the defence of Australia, we pay too little regard to what was of far greater significance: denying Imperial Japan that critical maritime defensive perimeter.

Viewed dispassionately, US operations in the Solomon Islands were the more consequential in achieving that outcome. Leading the Solomons campaign should have been our burden, but Australia did not possess the military strength that the age demanded.

After 1945, the struggle for mastery in Eurasia took a different turn as the US engaged economically and militarily in arbitrating the geopolitical fate of the supercontinent, through the containment of Soviet Russia, and communist China after 1949, the economic power of the Marshall Plan, the strategic power of NATO and the system of alliances in the Asia-Pacific region after 1951.

From 1948 to 1991, there occurred a titanic struggle for geopolitical mastery across Eurasia, which ultimately was decided by the collapse of Soviet Russia and the staying power of the offshore hegemon, the US, and its European and Asia-Pacific allies and partners.

This victory was not cashed in after 1991 for a new global order that might have seen, for the first time, global economic integration and political governance supplant Eurasian geopolitics. Central to this would have been the bringing of a technocratic China into a global system of interconnected trade, investment and technology development, as well as into international institutions, where it could play a constructive role.

Had this – and political reform in post-Soviet Russia – succeeded, it is possible to think a stable global geopolitical order could have been established for the first time in human history, anchored in a functional US-China bipolarity. This was not to be.

On another August 8, this time in 2008, the geopolitics of Eurasia erupted into another cycle of struggle. On that day, Russia invaded Georgia like a 1930s aggressor, and the Summer Olympics opened in Beijing, with China unveiling to the world a nationalistic and assertive view of itself and its place in the world order.

The US was in the throes of the global financial crisis and wondering how it was going to extricate itself from Iraq and Afghanistan. Talk of US decline increased. In January 2009, a US administration that overemphasised restraint in the exercise of American power took office. Within weeks it was being tested in the South China Sea.

Today, the “grand chessboard” of Eurasia continues to be the decisive geopolitical theatre, to paraphrase Polish-American political scientist Zbigniew Brzezinski.

The alliance between China and Russia is broadening and deepening, and the axis of those two powers, along with Iran and North Korea, is more integrated than ever was the first Axis of the 1930s and ’40s. From the Atlantic coast of Portugal to the Bering Strait, from Arctic Norway to the Singapore Strait, the supercontinent of Eurasia contains the bulk of the world’s population, natural resources and economic power. Any Eurasian hegemon that managed to establish strategic control of the interior lines and networks of continental trade, investment, transport, energy, data and technology flows would become the dominant global power if it was also a significant sea power that was able to hold at bay US sea power.

In light of these developments, we are rediscovering the insights of those earlier geopolitical strategists such as Alfred Mahan, Halford Mackinder and Nicholas Spykman, who were in various ways concerned with the generation and management of strategic power in the heartland, rimlands and littorals of Eurasia and the oceans around it. Each brought a different lens to the problem. For Mahan, sea power was crucial. For Mackinder, it was land power. For Spykman, air power was transformative.

Unfortunately, today we lack strategists who display similar originality and broad perspective, especially when it comes to space power and cyber power. These newer forms of power overlay geography without displacing it. Hopefully, each will one day have their great geopolitical strategist.

In the face of the possible emergence of a Eurasian hegemon, the US has a vital interest in acting as the indispensable strategic arbiter in Eurasia. To do so, it will need to work with, and through, a network of alliances and coalitions in the Euro-Atlantic, Middle Eastern and Indo-Pacific regions. With these networks, and its economic dominance, technological prowess and military might, the US could so act, in its own interests, for decades to come – especially if Europe, India, Japan and others were to play their parts in a counter-hegemonic strategy around the periphery of Eurasia.

Living with a threat focuses the national mind.

It certainly does in those frontline states around the periphery of Eurasia, such as Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, The Philippines, Vietnam, India, Saudi Arabia, the Gulf states, Israel, Ukraine, Poland, the Baltic states, Finland, Sweden and Norway. The US does not need to hold the entire length of the strategic perimeter of Eurasia on its own. It can work in partnership with these and other frontline states, whether in alliance or in looser arrangements, to check and contest the Eurasian axis.

In addition to working with the frontline states, a successful counter-hegemonic strategy also will require the securing of several crucial strategic points, as defensive lines and as bastions for power projection. These are Canada, which along with Alaska protects the northern and Arctic approaches to the US; the Greenland-Iceland-British line, which protects US sea power in the North Atlantic and checks Russia sea power there; Britain itself, as a forward operating base into Europe; the Gulf states and Diego Garcia, which enable power to be projected into southwest Eurasia; and Australia, which guards the southeast littoral region of Eurasia, at the join of the Pacific and Indian oceans, and from where US power can be projected into the eastern rimlands and littorals of Eurasia.

There is a need to explore how Indonesia sits within this geopolitical framing. Any meaningful military threat to Australia would have to come through Indonesia, while any US-Australia power projection into Eurasia would have to traverse the same axis in reverse. Australia’s strategic relationship with Indonesia is unfinished business, but its geopolitical logic is clear. Both countries would be more secure if they were committed to assisting each other in the event of either, or both, being attacked militarily.

We like to think of ourselves as a peaceful people, scarred by the memory of foreign wars. For many Australians, defending our sheltered land, and avoiding distant entanglements, still make a great deal of sense. However, when it comes to geopolitical strategy, Australia would be best served by playing its part in the US-led counter-hegemonic strategy in the struggle for mastery in Eurasia.

This strategy will have to be explained to the Australian people – and possibly argued for, as it might not be readily accepted by a people who wish to be left alone. The intended effects of such a strategy extend over vast transcontinental and oceanic distances, well away from Australia. Explaining this will be more difficult than explaining the need to defend against a threatening neighbour, of which Australia has none.

In terms of foreign policy, much of what Australia needs to do on the international stage can be done independently, or at least with minimal reference to this geopolitical struggle. Many trade, investment, people-to-people links and diplomatic initiatives can all be fostered as being beneficial in their own right. That said, few areas of international policy are untouched by geopolitics and careful decisions still need to be made, for instance in technology policy, where US-China rivalry is intensifying.

China’s deep integration into the global economy does not dispense with geopolitical dynamics. It complicates them in a way that has never been seen before. Previous aspirant hegemons such as Imperial Germany and Soviet Russia were simply never so central to the trading and investment structures of so many other economies.

At times, Australian foreign policy discourse appears to be premised on naive ideas. War in the Indo-Pacific region is to be avoided “at all costs” because it would be catastrophic.

Really – what if the alternative would be worse? Or that it would be in our interests to “triangulate” a position of relative autonomy between the US and China. Really – are we saying that the problem is their rivalry? Or that Australia and Southeast Asia might somehow present a united front in the face of US-China competition and confrontation. Really – even if it could be achieved, would this be desirable?

In a complex and at times confusing international scene, often things do not make sense. However, when we step back and see the picture in full, pieces quickly fall into place. Thinking about the geopolitical dynamics of Eurasia tends to explain a great deal. The vital elements of Australia’s geopolitical strategy – such as contributing to regional deterrence against China, acquiring long-range, nuclear-propelled submarines and building up US combat power in northern Australia – make more sense if we see them as examples of Australia working with others to counter the emergence of a hegemon in Eurasia.

We cherish our sheltered land. Billions would love the same blessing. While the emotional longing for quiet security has been a constant in the Australian national imagination, hard strategic realities have always been closer than they might appear.

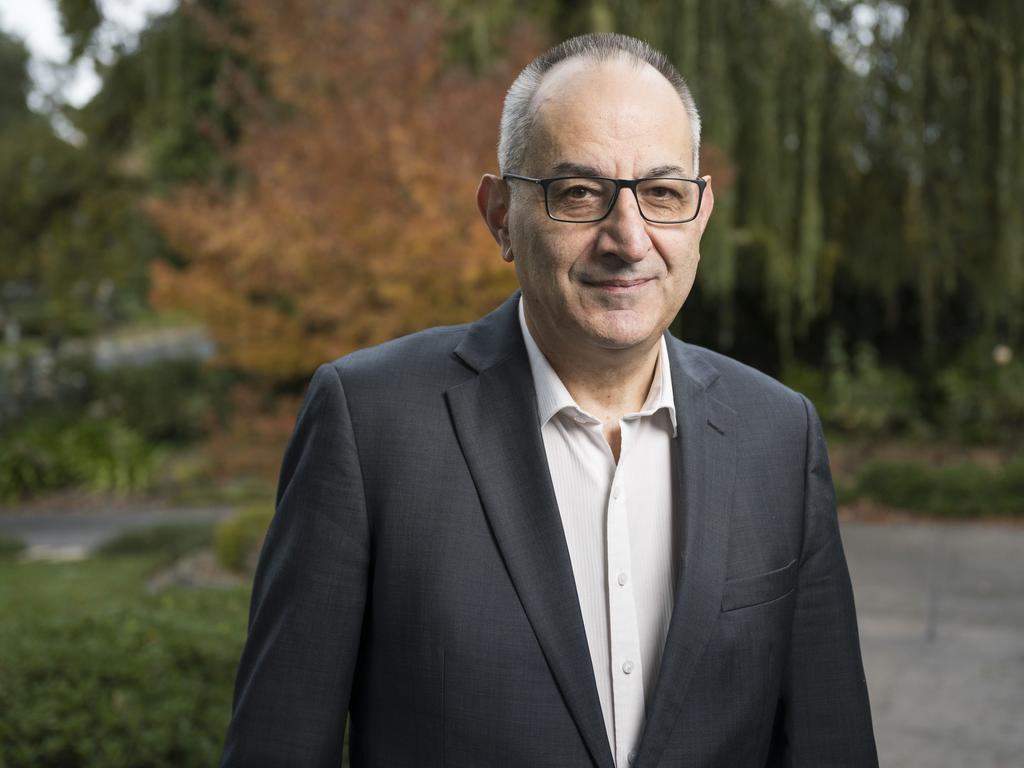

Michael Pezzullo is a former deputy secretary of the Defence Department and was secretary of the Home Affairs Department until November last year.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout