How Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping have joined to thwart the West

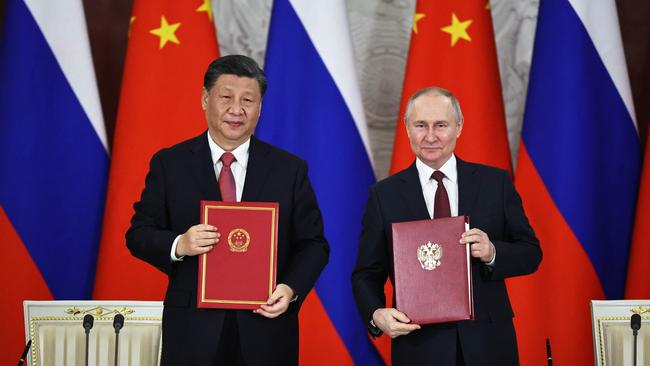

The world’s two most powerful dictators, friends without limits, have a lot in common, all of it bad. This was a summit of perhaps historic consequence.

“The two sides expressed serious concern about the consequences and risks to regional stability of the establishment of the Trilateral Security Partnership (AUKUS) by the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia and related nuclear-powered submarine co-operation programs.

“The parties call on the US to stop undermining international and regional security and global strategic stability in order to secure its unilateral military advantage … The parties express great concern over the ongoing strengthening of NATO’s ties with the countries of the Asia-Pacific region on military and security issues.”

It is the modern world in the boldest geo-strategic colours. In Western societies, leaders talk, rightly, of preserving an international rules-based order. Yet just a couple of days after the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for Putin, for war crimes, Xi arrived in Moscow for a visit of several days, lavishing praise and support on Putin, who certainly lavished back.

Xi came bearing gifts, and exacting a price.

Says Mike Green, America’s pre-eminent Asia geo-strategic specialist and now head of the US Studies Centre at the University of Sydney: “The summit itself is confirmation that both Xi and Putin prioritise their ideological struggle against the West over their own nations’ economic wellbeing.”

Not to pay excessive heed to the two dictators’ sense of grandeur, but this was a summit of perhaps historic consequence. It exposed geo-strategic reality, and it changed geo-strategic reality.

Malcolm Davis of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute says the summit’s purpose is clear: “The summit is a huge finger in the face of the ICC and the international rules-based order. The two states are co-ordinating their efforts against Western democracies. That’s very worrying.

“Russia is weak at the moment, but it could come back and rearm itself, especially if it gets a ceasefire, and threaten European nations again.”

Davis echoes other analysts when he concludes that Beijing now dominates Moscow, but it’s still a two-way street. Xi is determined that Putin will not face ultimate defeat in Ukraine and that he should not be deposed internally. This leads Davis to a controversial judgment: “I think the Chinese will start arming the Russians because a Russian defeat would hurt Xi.”

The Chinese consistently say they have no intention of directly selling Russia lethal weapons, but the Americans, and indeed all of Western intelligence, plainly think it’s on the cards. Senior figures, such as US Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, keep warning Beijing not to do this.

The month of March may be regarded by future historians as pivotal in strategic history. It has displayed almost an operatic symmetry, as though a composer, both librettist and choreographer, had produced a series of plot-entwined arias.

The month began with Beijing sponsoring a strategic rapprochement between Iran and Saudi Arabia. It’s the first time China has ever played this role in the Middle East. It’s directly in conflict with US strategic interests. Barack Obama and now Joe Biden have both handled the Middle East disastrously. Obsessed with the two futile ideas of beating up on Israel over the Palestinians and organising an American detente with Iran, both administrations neglected American friends in the Middle East and abdicated the traditional US role of regional security stabiliser.

Once such a vacuum might have been filled by Russia. But today Washington’s superpower competitor is Beijing, which has global ambitions and capabilities. Henry Kissinger observed: “China has in recent years declared that it needs to be a participant in the creation of a new world order. It has now made a significant move in that direction.”

But where Biden is weak in the Middle East, he’s relatively strong in Asia. Thus March also saw the stunning announcement of the AUKUS deal. A creation as elegant as it is purposeful, this is the lyric soprano aria of the geo-strategic moment, Tosca on the balcony (though hopefully with a different ending). Australia gets first three US nuclear-powered Virginia-class submarines, then an AUKUS sub jointly designed with the Brits, who will be replacing their Astute-class nuclear attack subs.

AUKUS has been hailed around the world. It’s not only a huge win for Australia, it demonstrates US and British resolve. It materially affects allied military capability at the highest level, drives deeper defence technology intimacy between the AUKUS partners and expands allied nuclear-propelled submarine making from three yards – two in the US and one in Britain – to four, with a new capability in Adelaide.

The Economist magazine, never one to give the US easy marks, calls AUKUS a model of allied co-operation. David Ignatius at The Washington Post describes the summit of Biden, Anthony Albanese and Britain’s Rishi Sunak, as a “present at the creation” moment for modern America. Biden has put an enormous amount of presidential time into AUKUS.

Then came the historically novel event of East Asia’s two sides reaching into Europe’s deadliest conflict. They were mirror image opposites in intent and design. Just as Xi was in Moscow helping Putin, one dictator to another, Japan’s Prime Minister, Fumio Kishida, was in Ukraine visiting President Volodymyr Zelensky, one democrat to another, the first time a Japanese prime minister has visited a war zone since World War II. Kishida’s gesture was as clear as Xi’s, but faced in the opposite direction.

Xi’s visit brings powerful benefits for Putin. China is strong, Russia weak. Xi’s visit enhances Putin’s prestige, domestically and internationally. Any Russian contemplating how to get to a post-Putin Russia now has to take into account Xi’s commitment of Chinese power to making sure Putin doesn’t fail.

This applies internationally too. China enables Russia’s war effort, becoming Moscow’s top trade partner. Russia has reoriented its economy towards China. At the same time, Beijing monetises its strategic support by gaining unlimited access to Russian energy resources at bargain prices.

This degree of Chinese support for Russia may force a rethink of Western strategy in Ukraine. Russia’s losses in men and treasure have been so great, and its military performance so poor, that Western analysts speculate about Russian military collapse, or Putin being replaced, or that Moscow might withdraw from most of Ukrainian territory to end the fighting.

Paul Dibb, former senior defence and intelligence official and one of our most experienced analysts of Russian grand strategy, thinks that’s baloney.

He tells Inquirer: “The idea of negotiations for a peaceful settlement in Ukraine is cloud cuckoo land. Putin refuses to recognise that there is a country called Ukraine. The Russians are a tragic people, used to difficult living conditions. They’re not likely to overthrow Putin. There’s deep Russian paranoid thinking about Crimea and Putin plays it like a violin. Putin is in this conflict for the long haul and he will test Western resolve in the long term.”

Perhaps the West should significantly increase the scale and type of weapons it supplies Ukraine so it has a chance of winning more decisively, more quickly. Putin, backed by Beijing, is unlikely to collapse. While Russia’s losses have been enormous, Ukraine is daily having its infrastructure destroyed, apartment buildings, schools and hospitals pulverised by Russian artillery, missiles and drones, its people murdered and traumatised. Even Ukraine’s magnificent courage is surely not endless.

Beijing has handled the public side of Xi’s Russian visit shrewdly, though it is still not without cost for China. Xi went to Moscow allegedly with a peace plan. As a peace plan it’s self-contradictory nonsense. It claims to recognise the sanctity of international borders but doesn’t call on Russia to withdraw from Ukrainian territory it has conquered. It calls for a ceasefire, with all of Russia’s territorial gains intact, and lifting of sanctions on Russia. As Dibb observes, as a peace plan it has zero chance of success.

But global media reporting Xi as carrying a peace plan is splendid propaganda for Beijing. It plays well with the global south, that vast collection of nations that don’t enjoy developed world living standards. Some of them are democratic, many are not. They haven’t joined the condemnation of Russia. They are concerned with their own economic welfare and consider Chinese money just as good as American money.

There is an epic battle, between the two rival camps, democrats and dictators, Washington and Beijing, for support in the global south. As former British foreign secretary William Hague pointed out, most of the global south doesn’t share the West’s political values. This is perplexing because Western nations believe democracy and human rights are universal values. Much of the global south are not themselves egregious human rights abusers but won’t allow such considerations to be strong factors in their own foreign policies. Western powers need to approach such nations with sophistication and a sensitivity to the nuance of each case.

Xi as the man with a peace plan also plays well with the far right of Western politics, the modern iteration of communism’s “useful idiots” who fatuously equate America’s undoubted shortcomings with the wholesale dictatorships of Russia and China. If Xi has a peace plan, they say, let’s go with it so we can stop giving Ukraine money or weapons. This also plays well on the left, which is traditionally hostile to anything resembling Western military effort.

The two big nasty surprises for Putin were Ukrainian resolve and Western resolve. Xi’s “peace plan” is an effort to undermine Western resolve.

Yet at the same time Xi’s actions and words are so cynical, so clearly designed to sustain Putin, that they hurt Beijing’s reputation with all Western governments, even, perhaps especially, centre-left governments such as those of Biden and Albanese. These governments see clearly what China is doing.

Which brings us to Xi and Putin’s condemnation of AUKUS. Says Dibb: “The more these two authoritarian powers bray shrilly about AUKUS, the more it’s clear it worries them. Why? Partly because the US Virginias are the Rolls-Royce of submarines. The Chinese and Russians cannot detect American submarines. The Americans are a long way ahead in submarine technology.”

Green suggests there is still a belief in Beijing that it can divide Australia from the US over AUKUS, and of course Beijing is much encouraged in this mistaken thinking by the interventions of Paul Keating and other similar recitations of arguments strikingly similar to Chinese government talking points. Beijing hears the Albanese government talk of stabilising the relationship and comes to the conclusion that the political pressure on the Albanese government to keep the relationship steady is such that it will make concessions to Beijing.

Green thinks Beijing underestimates the strategic sagacity and resolve of the Albanese government. He says Beijing typically misreads democratic sentiment.

Davis says that clearly AUKUS has the Chinese riled: “They don’t like the nuclear subs, but they also don’t like pillar two of AUKUS, which is more likely to produce extra military capability before the nuclear subs.”

Pillar two of AUKUS covers US-UK-Australia co-operation on artificial intelligence, quantum computing, robotics, hypersonic weapons and advanced undersea combat. For this co-operation to be effective, the US will need to make special exceptions for Australia and the UK to be allowed to participate fully in US defence research efforts.

It would be absurd, nonetheless, to describe the world as enduring a full-blooded cold war. Last year, the US still imported $US537bn worth of products from China and exported $US153bn to China. That trade would be cut off in a minute if there were military conflict. China’s economy would be devastated. Australia’s trade with China would also cease instantly.

As others have pointed out, similar economic integration among the great European powers did not prevent World War I. It is inherently dangerous that two of the world’s three most powerful nuclear-weapons states are led by one-man dictatorships.

Putin believes the fall of the Soviet Union was the greatest tragedy of the 20th century. Xi may well agree. Says Green: “Putin is nostalgic for the old Soviet Union. Xi is nostalgic for the ideas of Chairman Mao. Xi truly believes in Marxism-Leninism. He believes the Soviet Union didn’t have to collapse, Gorbachev chose to collapse it.”

Davis thinks China is clearly the dominant ideological power but that its ideology is very sympathetic to Putin: “Xi wants to bring the international rules-based order down and replace it with a Chinese-led international order, which would make the world safe for authoritarianism.

“What he ultimately wants is democracy on the ash heap of history.”

The world’s two most powerful dictators, friends without limits, in their own words “dear friends”, have a lot in common, all of it bad.

Extracts from joint statements by China’s President, Xi Jinping, and Russia’s President, Vladimir Putin, following their Moscow summit: