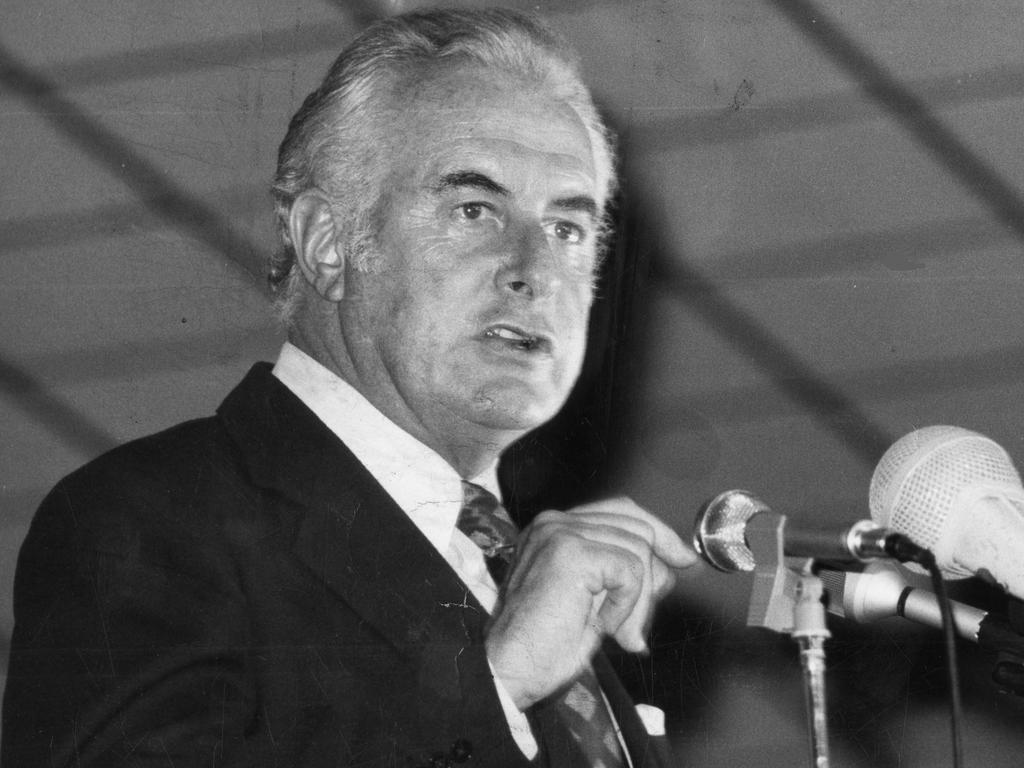

Whirlwind Whitlam was a flat-out force of nature

From the moment he won, the great reformer was at full throttle – and never slowed down.

When Labor won the December 2, 1972, election – 50 years ago this week – Gough Whitlam believed there was no time to waste. While Whitlam’s home at 32 Albert Street, Cabramatta, hosted a boisterous Saturday night party as friends, neighbours, staff and journalists spilled into the front and back yards, the incoming prime minister had little time for revelry.

Whitlam was up early the next morning and organised to fly straight to Canberra. His VIP plane touched down in the nation’s capital on Sunday afternoon. The Labor leader met with senior public servants and planned for a quick swearing-in of a two-man duumvirate government comprising himself and his deputy, Lance Barnard, on Tuesday.

Australians had never seen anything like it. While Labor won 49.6 per cent of the primary vote and 52.7 per cent of the two-party vote, a swing of 2.5 per cent, it had a majority of just nine seats. But Whitlam threw caution to the wind. There was work to do. The “backlog” of policy changes needed was too great, he argued.

Governor-General Sir Paul Hasluck, outgoing prime minister Billy McMahon and senior public servants had never seen anything like it either. Nor had Buckingham Palace.

The transition to government was to take place sooner than they expected. Recently declassified notes, diaries and letters provide a fresh insight into the historic change of government.

Sir John Bunting, secretary of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, met with Whitlam on Sunday and Monday in Canberra. Whitlam also consulted with the electoral commissioner and was told that all seats may not be declared until about December 20. Accordingly, Bunting informed Hasluck to prepare for an early swearing-in.

“Whitlam had it in mind to propose that he and his deputy leader should be sworn in at once as ministers for the entire range of commonwealth departments to form an interim government until such time as the swearing-in of a full ministry could take place,” Hasluck recorded in a note that is now located in the National Archives of Australia.

To facilitate the duumvirate government, with Whitlam holding 13 portfolios and Barnard 14 portfolios, Whitlam also consulted the secretary of the Attorney-General’s Department, Sir Clarence Harders.

Harders advised there were no “legal or constitutional impediments” to establishing a two-man government.

McMahon phoned Whitlam at home in Cabramatta on the Sunday after the election to concede. At 11.30am on Tuesday, December 5, McMahon met with Hasluck at Government House at Yarralumla, returned his commission and advised him to call on Whitlam to form a government.

However, McMahon expected to remain in an interim capacity until the ministry could be sworn-in, most likely Thursday that week. This is what McMahon and Hasluck had discussed on Sunday morning, according to Hasluck’s notes. But his prime ministership would expire within hours.

McMahon also expected to meet with Whitlam for a customary cup of tea and conversation. This is what Ben Chifley and Sir Robert Menzies had done when there had last been a change of government in December 1949. But this would not happen either.

In a reflective mood, McMahon talked with Hasluck about the campaign and the future. “(McMahon) expressed a mixture of disappointment and of relief at the results of the election,” Hasluck noted. “He was not chastened, or so it appeared, by the defeat which he thought was due to the faults of others and the wickedness of the Labor Party.”

Who should lead the Liberal Party? Don Chipp, Malcolm Fraser, Phillip Lynch, Andrew Peacock and Billy Snedden were mentioned. “None of them was any good,” McMahon told Hasluck. “They were just not good enough for leadership.”

McMahon never finished his memoirs but an outline, found in his papers at the National Library of Australia, reveals that he planned to savage the Liberal Party’s federal secretariat and its “disappearance during the 1972 election campaign”.

Whitlam met Hasluck after he had seen McMahon, at 12.15pm. Hasluck congratulated Whitlam “on his victory” and invited him to form a government. Whitlam advised that a two-man ministry be formed. They organised a swearing-in to take place later that afternoon.

At 1.45pm, Whitlam phoned McMahon. McMahon made a note of the conversation, which is now among his papers at the National Library. Whitlam informed a stunned McMahon that the change of government would take place that afternoon.

“I have party rules which I have to adhere to and they require the election of members of the ministry,” Whitlam said to McMahon. “(But) there were certain matters,” he said, “which must be done immediately to carry out electoral promises.” Therefore, Whitlam said he had consulted with Hasluck and would be sworn-in with Barnard within hours.

Whitlam confirmed there was no time for a meeting between incoming and outgoing prime ministers. Whitlam stressed to McMahon that he “did not want to create the impression that he was rushing in to grab the spoils”. The call ended with McMahon wishing Whitlam “good luck” and said he hoped he was given “a fair go”.

The swearing-in of the 21st prime minister, and Australia’s only duumvirate government, took place at 3.30pm at Government House. In private, Whitlam told Hasluck that should “anything happen” to him or Barnard, such as “a fatal air crash”, then he should call on Frank Crean to become prime minister. Whitlam identified Barnard and Don Willesee as his “closest confidants”.

On December 7, Hasluck wrote to Buckingham Palace. This letter was made public by the National Archives only in January this year.

He explained Whitlam’s reasoning behind the two-man ministry, given the uncertain outcome in several seats, and added that he wanted “to give prompt effect” to policy commitments and it would be “ungracious to his opponents and unacceptable to his supporters” to ask caretaker ministers to make them.

“(T)he two ministers have gone ahead with great despatch and decisiveness,” Hasluck told Sir Martin Charteris, the Queen’s private secretary. “They may have alarmed some citizens while gaining a good reputation for promptness and firmness with others.” He added that Whitlam and Barnard had “behaved with decorum and full respect”.

Hasluck offered a withering assessment of McMahon, a former cabinet colleague, which was read by the Queen.

“I had originally no respect for his character and a poor opinion of his qualities as a politician, but throughout his term as prime minister I was increasingly dismayed by the effect of his shortcomings,” Hasluck wrote. “His term weakened the cabinet system, undermined the public service, made public relations exercises even shoddier than usual, lowered respect for the prime ministership, and eroded trust.”

Charteris welcomed the new Labor government, replying on December 18 that 23 years was a long time to have been in opposition. “(I)t will be very understandable if the first months of the new administration are accompanied by some political fireworks, some of them aimed at the spectators,” Charteris wrote. “But if the desire for change was the main motive in the minds of electors, this may show their wisdom. It seems from what you write that change was precisely what was needed.”

As the duumvirate ruled for 14 days, making far-reaching decisions, the Labor caucus was cooling its heels. It would not be until December 18 that the caucus would meet. It took five ballots to select a ministry of 27, the last at 9pm. After elections had finished, Whitlam took just 90 minutes to allocate portfolios. They were sworn in the next day.

Just two Labor ministers survive from December 1972 – Doug McClelland and Bill Hayden – and a third, Paul Keating, joined the cabinet in October 1975. Hayden and McClelland, who spoke to Inquirer, remain proud of the Whitlam government but are candid about its flaws.

McClelland, 96, served as media minister and special minister of state. He recalled the formation of the duumvirate and his astonishment watching “two blokes” effectively rule alone for a fortnight.

“Whitlam might have been a bit envious or jealous of Lionel Murphy (Labor’s Senate leader) so he decided that he and Barnard would be the ministry until the caucus met,” McClelland said.

“No one was going to challenge Whitlam … and we knew that this was only going to be for a short time, come what may.”

Hayden, 89, served as social security minister and treasurer. He recalled the tumultuous cabinet meetings and the frenetic decision-making.

“It was chaotic,” Hayden remembered. “Gough had good policies but the problem was they were implemented too rapidly … I thought we can’t keep going on like this and that Gough should have exercised more discipline over his ministers.”

The work of the duumvirate was labelled “rapid decision government” by the media who struggled to keep up with the pace of reform, along with the voters. So did the public service.

Bunting made a note for “future historians” chronicling these early days. Although the executive council had met, no cabinet or caucus meetings were held, and little public service advice was sought or given. Bunting asked his deputy to ask journalists or Whitlam’s staff for “the daily statement of decisions or actions” taken.

The Whitlam government came in like a whirlwind and the speed of change never slowed for the entire 1072 days until its dismissal on November 11, 1975. In an address to the nation on December 20, Whitlam said his rapid policy decisions were necessary and justified. He had sought and received an “unmistakeable mandate” to govern, and he would.

Troy Bramston is writing a biography of Gough Whitlam to be published by HarperCollins Australia in 2025.