Virgin: ‘No free sausage’: the airline that could ... until it couldn’t

When its founders nutted out the concept for Virgin Blue on the back of beer mat, they foresaw soaring success. But fast forward two decades ....

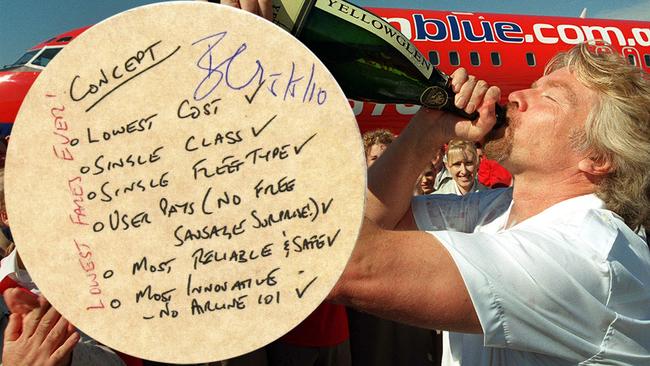

It was a funky, brash new entrant announced with huge fanfare by British entrepreneur Richard Branson in front of Sydney’s Custom House on November 30, 1999.

A low-cost carrier along the lines of Ryanair and Southwest Airlines, the new Virgin Blue caused front-page headlines with an announcement it would cut airfares between Melbourne and Sydney to an unprecedented $99 one-way.

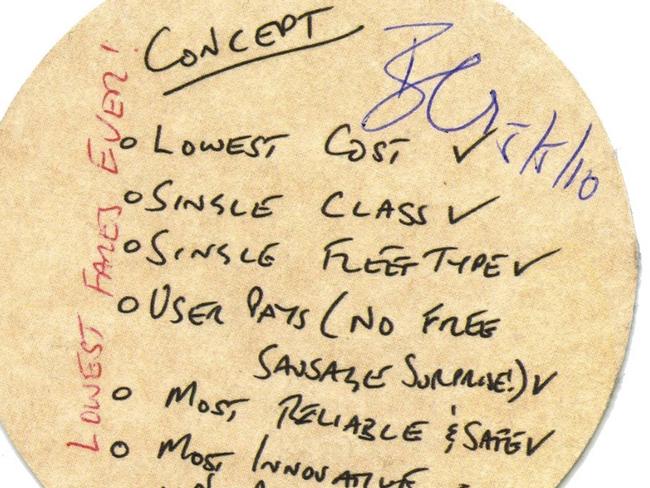

Co-founders Brett Godfrey and Rob Sherrard famously nutted out the concept for Virgin Blue on the back of beer mat in a London pub in 1993 after discovering airfares in Australia were up to 50 per cent higher than those for equivalent routes in Europe.

The beer mat outlined the basic concept with “lowest fares ever!” scrawled along the side in red. Virgin Blue would be the lowest cost carrier with a single fleet type and a user-pays concept for food that meant “no free sausage surprise”. It also would be the most reliable and safest airline as well as the most innovative.

Flight path: Click here to see Virgin’s journey so far

The pair refined the concept and took it to Branson, who agreed to provide $10m in seed capital and a $15m loan to fund a start-up called Virgin Blue, a play on its bright red planes and the fact Australians called redheads “bluey”.

Branson would remain a supporter of the airline and retain a 10 per cent stake, often travelling to Australia to pull his trademark PR stunts and preside over sometimes flashy product launches over the next two decades.

But nobody, including Branson, would have foreseen that 20 years later he would be appealing for government help to avoid a massive airline failure in Australia and to save his first airline love, Virgin Atlantic.

It has been a winding road that has taken Australia’s second airline from that ebullient announcement to the edge of the voluntary administration precipice.

Bumpy takeoff

Despite the hype from the flamboyant billionaire, Virgin’s launch in 2000 was modest with a staff of 200 and two Boeing 737-400 aircraft providing seven daily services between Brisbane and Sydney.

Nor was it all plain sailing: the Virgin team had been surprised when another low-cost carrier, Impulse Airlines, also took to the air that year with Boeing 717 jets.

This prompted a price war, with fares falling well below the $99 promised by Virgin to a more unprecedented $33 one-way. But the tough environment, including a low Australian dollar, took its toll on Impulse and it began flying regional routes under contract to Qantas in April 2001. It was later taken over by the bigger airline but its ghost would come back to haunt Virgin when the Boeing 717s were eventually used as Jetstar’s start-up fleet in 2004.

From the get-go, Virgin was very much about brand.

It was the cheap, fun alternative to the serious full-service airlines with an irreverent attitude that saw young, attractive flight attendants trading jokes with passengers. There was no in-flight entertainment — other than the crew — and passengers paid extra for food and drinks. They also had to book online or through call centres rather than at travel agents. Its advertising played to its youthful, funky image, with humour often a key ingredient. Underlining it all was cheap fares.

Behind the scenes, however, there was hard work, long hours and uncertainty. Growth was hardly exponential at one aircraft a month — two in some months — and the airline almost failed.

It was a thorn in the side of the failing Ansett that Air New Zealand attempted to neutralise by offering to buy it. Branson reportedly considered the offer but ultimately turned it into another publicity stunt by ripping up a cheque symbolising the offer at a controversial press conference. Days later, Ansett went into administration.

The Ansett administration proved pivotal for Virgin Blue as it took advantage of cheap aircraft made available by a weak market following the September 11 terrorist attacks in the US. It continued to open new routes and looked at moving into former Ansett terminals. Money for the expansion initially came from Chris Corrigan’s Patrick Corp, which poured $260m into the fledgling airline for a 50 per cent stake and allowed Virgin to broker a deal with Boeing for 50 aircraft at bargain-basement post 9/11 prices.

It further boosted its investment when Virgin floated its shares on the Australian Stock Exchange in December 2003, and by 2005 was Virgin’s major shareholder with a 62.5 per cent stake.

There were still worries for Virgin and none more so than the entry in 2004 of the well-resourced Qantas low-cost offshoot Jetstar, headed by a then little-known executive named Alan Joyce.

Nonetheless, the carrier entered a period of growth that would see the now majority Australian-owned carrier launch New Zealand-based Pacific Blue, the Velocity frequent flyer program and Polynesian Blue.

The first reinvention

As it took delivery of its 50th aircraft in 2005, Virgin was continuing to offer innovations such as Australia’s first web check-in and other, wider changes were afoot.

Godfrey was talking about reinventing Virgin as a “new world carrier”, a hybrid designed to attract more affluent customers without alienating leisure travellers. The airline also was moving away from its single-fleet strategy, a move that added costs, with an order for Embraer regional jets.

These proved popular with customers but were more costly than turboprops to run and would be phased out progressively a decade later as part of moves to rationalise the fleet and cut costs.

An even bigger change came in 2007 with the decision to launch long-haul carrier V Australia — an injunction by Singapore Airlines at that stage prevented the Virgin brand being used outside Australia — with wide-body Boeing 777s.

This would be another expensive exercise but one that gave the group the cachet of being an international operator.

Competition in the low-cost end of the market continued to intensify with the arrival that year of Singapore-based Tiger Australia and the following year Toll divested its controlling stake to leave Virgin Group again the biggest shareholder.

The airline launched a premium economy product in 2008 and V Australia’s inaugural flight from Sydney to Los Angeles in February 2009 marked a new era of trans-Pacific travel. Virgin also lodged an application with the US Department of Transportation for an alliance with US giant Delta Air Lines.

The Borghetti program

By the time Godfrey stepped down in 2010 and handed the reins to John Borghetti, Virgin was a different beast to the one that had started life on the back of a beer mat, but its costs were still below those of Qantas. But the biggest changes were yet to come.

Borghetti was keen to take some of the corporate market from Qantas and set about reinventing the airline as a full-service carrier with a new name, new uniforms, an award-winning business class, new lounges and a revamped Velocity program.

His new strategy, called the Game Change program, would see the livery change from red to white and Virgin Australia bring in costly wide-body Airbus A330 planes to compete with Qantas on coast-to-coast domestic routes.

Borghetti would expand Virgin’s web of international alliances with deals with Abu Dhabi-based Etihad, Air New Zealand and Singapore Airlines. The carrier would start flying to Abu Dhabi but dropped the route in 2017. Flights to Johannesburg and Thailand were short-lived. All three foreign airlines would take equity stakes in Virgin, although Air New Zealand eventually would lose patience with the Australian carrier’s losses and sell most of its stake to China’s Nanshan Group.

Virgin continued to expand, acquiring Perth-based Skywest Airlines in 2013 to give it a footprint in the resources sector and paying Singapore Airlines $1 for the remaining 40 per cent stake in what was now Tigerair Australia in 2014 to make it its low-cost arm.

The launch of business class across the majority of Virgin’s domestic network in 2012 had seen ticket prices drop as much as 40 per cent from those commanded by a Qantas monopoly.

But the ultra-competitive Flying Kangaroo was not about to take the incursion lying down. It threw capacity and cheap fares into the market in a bid to thwart Virgin’s market grab, at one stage threatening to add two planes for each that Virgin added.

“John took it way too far up-market from a cost point of view and Qantas had this line in the sand that it didn’t want crossed,’’ said one former airline executive. “John tried to eat into that space and that’s why they had the vitriol and the damage.”

The result was losses on both sides in what became known as the capacity wars and led to Virgin’s balance sheet carrying what new chairman Elizabeth Bryan would later describe as “significant leverage”. The net debt to which Bryan was referring to in 2016 was $2.1bn, less than half the $5bn reportedly now crippling the airline.

The shareholder base continued to change with Chinese groups HNA and Nanshan buying into the airline in 2016, making Virgin 40 per cent Chinese owned and prompting it to start services to Hong Kong.

The new service was designed to take advantage of its Chinese connections but failed to reach its potential and was canned in favour of a new route to Tokyo, thwarted by the coronavirus outbreak. Current chief executive Paul Scurrah took over in March, last year with a mandate to make the airline’s operations less costly and improve efficiency.

With its planes grounded, its cash reserves dwindling and its credit rating junked, Virgin Australia continues to seek government funding and has entered voluntary administration to allow it to restructure its debt and potentially seek new investors.

It isn’t clear who may take control of Virgin but private equity would be expected to strip out costs and exit the target company at a profit. TPG, for example invested $US66m in Continental Airlines, restructured under Chapter 11 bankruptcy and made $US640m.

Scurrah told a press conference yesterday that Branson cared deeply about Virgin Australia and was doing everything he possibly could to help the airline get through the administration. “It must be remembered that Richard takes a lot of pride in this company and it’s one of the airlines he pays a lot of attention to,’’ he said.

Industry watchers expect something to happen quickly and are not ruling out a move by Branson despite the fact he is concentrating on Virgin Atlantic and has offered his Caribbean island as collateral for a government loan. Either way, he’s still spruiking for Virgin Australia. As he told staff in a letter, “The brilliant Virgin Australia team is fighting to survive and need support to get through this catastrophic global crisis.”