Victory in the Pacific: Triumph of the people in their darkest hour

The hard-fought victory over Japan 75 years ago belonged as much to the women as it did the men.

But the clashing emotions of the revellers in Australia — joy tempered by relief, their exhilaration tinged with exhaustion, and beneath it an abiding, consuming sadness — reflected this country’s deeply fractured experience of World War II, the first and only total war we have waged.

The story of Australia’s war between 1939 and 1945 defies the easy telling because it was both all-embracing and wildly different depending on where you slotted into the vast machinery of the effort at home and abroad. This was the people’s war, and the hard-fought victory realised on August 15, 1945, belonged as much to the women who kept the newly established armaments works humming as to the men who fought in deserts and jungles, crewed warships and flew for the RAAF.

Australians fed the vast American armies and fleets that rolled back the tide of Japanese conquest in the Pacific, supplied the hungry millions in Britain who withstood the German bombing blitz of their shattered cities and kept the home fires burning when all seemed lost.

They made machineguns and artillery shells, aircraft engines, armoured cars and fighter planes. Sleepy towns such as Townsville in north Queensland hosted US bombers that ranged north to rain destruction on Japanese-occupied islands; submarines were repaired and rearmed in the Brisbane River while sprawling encampments of gum-chewing US marines and infantry sprang up outside Sydney and Melbourne. Coca-Cola and American idiom, including the F-word, were cheerfully appropriated from the Yanks.

The way Australians from all walks of life, of all ages and education came together built a bridge between the closeted, inward-looking nation that went to war at the behest of a distant mother country and the Australia that emerged six long, traumatic years later — stronger, resilient and with a more nuanced take on a world that had been remade by post-World War II’s triumphant but irreconcilable superpowers, the US and the Soviet Union.

The false security of empire was stripped away when Australia confronted an existential threat in the dark days of 1942 after the Japanese had run rampant, smashing the US Navy at Pearl Harbor, overrunning Hong Kong, The Philippines, what’s now Indonesia and the Malay Peninsula, capturing supposedly impregnable Singapore and nearly 15,000 Australian soldiers in the worst single blow ever dealt to this country’s armed forces.

With the army’s best and most seasoned troops engaged in North Africa and the Middle East, Labor prime minister John Curtin crossed Winston Churchill to bring them home and unashamedly turned to the US for the help a hard-pressed Britain could not provide. We now know that the Japanese high command had decided against launching an all-out assault on the Australian mainland. But to Curtin, Australia’s towering figure of the war, and the military brass in Melbourne the danger of invasion seemed not only real but probable.

Such were the macro settings that applied until the decisive US naval action at Midway in June 1942 sank four enemy aircraft carriers and Japan’s misplaced hope of forcing the Americans to the negotiating table to preserve their astonishing territorial gains. Australia, by then, was being retooled and reimagined as the launching pad for the great Allied counteroffensive.

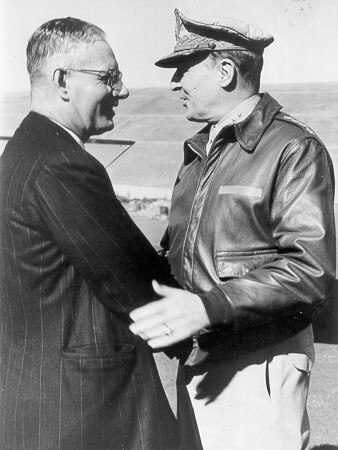

Douglas MacArthur had made his epic escape from cut-off Corregidor, outside Manila, and set up shop in the humid Queensland capital. Boastful and vain, the colourful four-star general could not have been more different to the unassuming Curtin. But he would exert an influence on Australia’s war that reflected the shifting power dynamic as the US build-up gathered pace.

More than anyone else, MacArthur was responsible for sidelining Australian soldiers as the fighting moved inexorably closer to Japan. It’s worth considering what Australia looked like back then. At the outbreak of World War II, we were a country of barely 6.9 million people, overwhelmingly white, Anglo, our values and ideals firmly anchored in king and country. When a minority group got a look-in it was the Irish-Catholics, not Indigenous people or those of colour.

Australia rode on the sheep’s back: wool was the major export earner. Few households could afford a car, which was likely to be British-made. Boys and girls — especially girls — would leave school at 14 to go to work. A scholarship-level pass, the equivalent of Year 8, was the norm. Bank clerks and draughtsmen might complete junior, or Year 10. The academically minded who went on to matriculate headed to one of only six sandstone universities in the land.

As was the case in World War I, Australia automatically went to war when Britain did on September 3, 1939, over Adolf Hitler’s invasion of Poland. No debate in the cramped national parliament in Canberra, few if any questions asked. The Great War of 1914-18 cast a long shadow. The fledgling nation was bled white at Gallipoli and in the trenches of the Western Front at the cost of 61,591 killed and more than 156,000 injured, gassed or captured, according to the Australian War Memorial. One in five of Australia’s frontline soldiers never returned.

Still, World War I was a sequential war, fought at a distance against a single foe, Imperial Germany and its allies including the Turks, more easily understood than the hydra-headed beast of the second world war that killed 39,000 Australians, injured 23,000 more and sent more than 30,000 into captivity.

“The challenge of trying to get your head around Australia’s involvement in World War II is that there is no single narrative,” says the Australian War Memorial’s head of military history, Karl James. “Our experience of the first world war is basically linear. You have got Gallipoli in 1915, the troops go to France in 1916, Belgium in 1917, France again in 1918. Everyone who is left standing then comes home. There is a sense of grief and mourning, a nationalistic notion of Anzac.

“Yet it is still largely a military experience where the job of those at home is to wait and weep.”

World War II was a vastly greater enterprise. Nearly a million Australians pulled on a uniform, more than two-thirds of them in the army’s all-volunteer expeditionary force, the 2nd Australian Imperial Force, or the mostly conscripted militia. The principal theatres of engagement were North Africa and the Middle East against the Italians and Germans before 1942, then Papua New Guinea and the islands of Bougainville and Borneo, until the nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki forced Japan to surrender, three months after the Nazis threw in the towel.

The touchstones of Australia’s war are the besieged Rats of Tobruk, bombarded for 241 epic days in 1941 by Axis forces that failed to dislodge them from their toehold on the Libyan coast; the 1942 heroics on the Kokoda Track of the outgunned and undertrained militiamen before the AIF arrived in the nick of time to save Port Moresby and chase the Japanese back over PNG’s Owen Stanley Range; the mateship of the prisoners of war as they suffered at Changi and on the Burma railway; the sacrifice of the thousands of Australian aircrew who served in British bomber command, perhaps the deadliest job going.

But as James points out, that’s not even close to the whole story: scratch hard enough and you will find Australians anywhere and everywhere there was fighting in World War II. Seconded personnel died on the doomed British battleships HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse when the Japanese sent them to the bottom on December 19, 1941, sealing the fate of Singapore.

Australian airmen took part in the Dam Busters air raid in May 1943 that destroyed the Mohne and Edersee dams above Germany’s industrialised Ruhr Valley, and made off in the Great Escape of PoWs from Stalag Luft III in occupied Poland in March 1944. Three thousand Australians participated in the D-Day landings at Normandy three months later and Australian warships pounded the beaches of Okinawa, the last stop before the Japanese home islands, when the US marines went in on April 1, 1945.

On the home front, Curtin moved to mobilise the entire adult population. He had come to office in October 1941 after the collapse of Robert Menzies’ United Australia Party-led government and another short-lived coalition under the Country Party’s Arthur Fadden. Notionally, all men aged between 18 and 60 were liable to be called up for military service. Civilians of working age were required to register with the Manpower Commission, itself a form of industrial conscription.

The government could decide where you worked and in what capacity. If you didn’t like the job, tough, there was always the Civil Construction Corps, which built roads, ports, gun emplacements and aerodromes in some of the continent’s most inhospitable reaches.

The Stuart Highway linking Darwin and Adelaide is a legacy of that effort. Of the 77,500 men who volunteered their labour or were “manpowered” into the CCC, 218 died in accidents or from disease. Never before had Australians given over such control of their lives to the government.

Food rationing was tightened. By 1944 the weekly allowance for a male adult was 2 ounces (57.6g) of tea, 6oz (170g) of butter, 16oz (453.5g) of sugar, 2.25 pounds (1kg) of meat. Clothing fabric and petrol were traded on a flourishing black market. Mark down the white wedding cake to wartime restrictions: a vanilla finish became the norm because pink icing sugar disappeared early on.

As in Britain and the US, the war pulled young women into jobs that had been the preserve of their fathers, brothers and husbands. More than 200,000 entered the workforce, and tens of thousands more signed on for the female branches of the services.

The railway workshops at Ipswich, west of Brisbane, were turned over to the production of shell and grenade casings. Four tram stops from MacArthur’s HQ in downtown Queen Street, Winifred Morrison, one of the war widows featured in our news coverage of the VJ Day anniversary, worked as a machinist in a Fortitude Valley printing plant, dreading a Japanese invasion.

“We didn’t know what was going to happen … it was a bit like this COVID virus going around now,” the 93-year-old remembers. “Everyone was worried and that went on for years and years. It was quite an awful time.”

The prize of full employment during the war years, never before achieved, ushered in decades of relative prosperity after the guns fell silent. Armament-making transitioned into a domestic car-building sector and heavy industry, all shielded by hefty tariffs. Post-war migration from southern Europe brought in Greeks and Italians, as well as the 10-pound Poms on assisted passage. The mantra of “populate or perish” held sway, a visceral reaction to the anguish of 1942.

But it took British military historian Max Hastings to shout the suspicion that had been expressed sotto voce here: that after the troops’ exploits at Bardia, Tobruk and El Alamein in North Africa and closer to hand at Kokoda, Milne Bay and the bitterly protracted 1942-43 battles of the beachheads at Buna-Gona in northern PNG, the Australian Army went missing in action. “A trauma overtook the nation which divided its people, demoralised its forces and cast a lasting shadow over the memory of the Second World War,” Hastings wrote in his 2007 book, Nemesis, triggering a furious debate.

Not surprisingly, the consensus among Australian historians is that Hastings got it wrong. Paul Ham, who has written well-received books on the Kokoda campaign and Australia’s war in Vietnam, says Hastings misses the point that MacArthur shunned the Australians because from 1943 he no longer needed them in his southwest Pacific command, swelled by the arrival in bulk of US ground forces. “I don’t accept his argument that the Australian troops were somehow fragile … that they didn’t do the job expected of them,” Ham tells Inquirer. “The fact is they weren’t allowed to do the job because MacArthur had engineered the Australian Army out of the war. The record is very clear on this.”

Former governor-general Sir Peter Cosgrove has a personal stake in the argument. His father and maternal grandfather served in the 2nd AIF and an uncle, an RAAF combat pilot, was killed on operations off PNG in 1943. Cosgrove himself saw action in Vietnam, where he was decorated for valour in 1971 as the commander of an infantry platoon, and went on to lead the UN-backed peacekeeping mission to East Timor in 1999, ending his military career as chief of the defence force. Quite a pedigree.

When he thinks of Australia’s war, 1939-45, Cosgrove likes to do it through the feats of Tom “Diver” Derrick, who was awarded the Victoria Cross for his crazy-brave attack on a heavily defended Japanese position at Sattelberg, New Guinea, in November 1943. Derrick’s mates in the 2/48th Battalion believed he should have been put up for the VC when he single-handedly knocked out three German machinegun positions during the Battle of El Alamein. This time, he scaled a cliff face while under heavy Japanese fire and silenced no fewer than seven enemy machinegun posts, before leading his platoon in a charge that destroyed a further three.

“Our people had a magnificent war but in the jungle it was fought on a narrow frontage,” Cosgrove says. “When Diver Derrick won his VC he was going up a ridge line about as wide as the aisle of a Sydney suburban train. That’s how that phase of the war was fought, with personal weapons, hand to hand. The generalship was not the same spectacular wheeling around of divisions that you had in the Middle East, but the soldierly accomplishments were magnificent.”

John Edwards, author of the masterful two-volume account John Curtin’s War, says MacArthur reneged on a commitment to use Australian troops in the 1944-45 campaign to recapture The Philippines partly because Australia’s top commander, Field Marshal Thomas Blamey, insisted that the Americans take a three-division Australian force in its entirety or not at all, and mostly because MacArthur didn’t want to share the credit.

Edwards says the counterfactuals of the Pacific War — the what-ifs had the Coral Sea and Midway naval engagements not been fought or had been won by the Japanese — still tantalise. Port Moresby would have fallen and the Japanese could well have seized Darwin next, Edwards believes. “I think this would have been the natural logic of that conflict,” he says.

“It’s not to say they would have taken all of Australia … just the parts of the north of the continent useful to them as forward bases. They would have been backed up by their own sea power, transport, and Australia would have confronted the problem of manoeuvres over vast areas of desert with very poor transport. It might have well seemed to them to be worthwhile.”

Historian Geoffrey Blainey suggests that an emboldened Japan could have launched a small-scale invasion of Cape York Peninsula if — and he stresses it’s a big “if” — the basically neutral tactical outcome of the Coral Sea in May 1942 had not spooked an accompanying Japanese amphibious force into veering away from Port Moresby, a strategic win for the Allies.

A full-scale occupation of Australia was never contemplated by the Japanese, Blainey insists. “There was little point in it,” he says. “One reason is dazzlingly clear. Japan’s experience while invading China in the 1930s taught a simple lesson: it is just so hard to invade a big landmass with a long coastline and wide interior.”

Seventy-five years on, we can only marvel at what Australia’s brave and great-hearted World War II generation achieved. Through their blood, sweat and tears they earned a revered place in history — and a nation’s undying gratitude.

They danced in the streets on this day 75 years ago when news broke that the Japanese had surrendered, ending the bloodiest and most destructive armed conflict in human history.