As the Pacific theatre opened, the nation was ill-prepared

Our wartime crisis has largely been forgotten but we’d do well to heed the lessons of 1941-42.

It is vital to remember all those Australians who gave so much, even their lives, to the Allies’ victory in 1945. It is also vital to learn the lesson taught by those dismal months of 1941-42 when victory seemed far away, and hosts of women and men feared Australia might be invaded in the north and perhaps defeated.

Australia definitely was not as well prepared for World War II as for World War I. Whereas public opinion was strongly in favour of joining the war against Germany in 1914, it was more divided and less dedicated when the next war against Germany began in 1939.

This second war was more disturbing and dispiriting. Almost everything favoured Adolf Hitler for two years. Conquering France in 1940 with lightning speed, he seemed likely to destroy inner London and invade Britain. With the help of Benito Mussolini’s Italy, he occupied most of the Mediterranean’s shoreline. In 1941 it seemed possible that he would capture Libya and Egypt and the all-important Suez Canal. This was the theatre of war in which Australia’s army and navy were most active until 1942.

Britain and its allies, especially Canada and Australia, were briefly the main opponents of Hitler until June 1941, when they were unexpectedly joined by Russia. The brief friendship of Hitler and Joseph Stalin ended dramatically when, to Stalin’s dismay, his territory was invaded by the Germans. By the wintry close of that year Russia seemed to be in danger of being defeated by the fast-advancing armies of Hitler. Even Britain, fighting on so many fronts, was seriously overextended.

That strategic situation gave Japan the opportunity of invading the Soviet Union from the east or invading the British, Dutch, French, Portuguese and US colonial interests to the south. Goaded by the US, Japan decided to make a simultaneous attack on territories stretching all the way from East Asia to Hawaii. It was one of the most successful campaigns in the history of warfare.

Japan’s supremacy in the air was unexpected. It had been widely believed in England that the Japanese pilots had a physical defect that prevented them from flying effectively at night.

There was a parallel belief, also false, that the Japanese fighting aircraft were so slow in the air that they would be easily matched by the Brewster Buffalo and other inferior aircraft sent by Britain to defend Singapore.

The US naval base at Pearl Harbor was attacked by Japanese aircraft on Sunday, December 7, 1941. In fact a strip of coast in British Malaya had been invaded an hour or two earlier. In the following week the US air force defending The Philippines was shattered, and an attack by Japanese dive-bombers sank the great British warships Prince of Wales and Repulse not too far from the naval base in Singapore.

The leader of Australia’s industrial war-effort was Essington Lewis, an engineer and chief executive of BHP, whose extensive steelworks and allied factories were centred on Newcastle and Port Kembla.

Visiting Japan for a fortnight in 1934 and closely inspecting many workplaces that were out of bounds to journalists, Lewis was surprised to discover that Japan “was armed to the teeth”. In an emergency it could build 100 aircraft a day at a time when Australia had less than 50 active fighting planes.

Back in Melbourne he formed a syndicate called the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation, which in 1939 built the first Australian military aircraft, a simple, lightly armed trainer-plane called the Wirraway. Later came fighter bomber aircraft that really held their own. It was remarkable that we mass-produced planes before we mass-produced cars, the first being the now-nostalgic Holden.

In 1940, Robert Menzies as prime minister had placed Lewis in charge of the nation’s industrial war-effort, and eventually a huge workforce of men and women were producing war equipment of a variety that surprised the few foreign industrialists who visited wartime Australia. Lewis, pre-modern in his business ethos, achieved this huge task without seeking payment from the government.

For five years Lewis wielded more power than the high medical officials whose diagnosis of the coronavirus pandemic we now hear each day. He shunned publicity but was known by sight to the hundreds of thousands of workers in munitions and aircraft factories and shipyards, for he inspected each site regularly and minutely.

Inside Australia the first news from Pearl Harbor was bewildering. A war with Japan had been more or less expected. The heavy loss of life was not.

John Curtin had been prime minister for only two months and had no experience even as a junior minister. Moreover he led a Labor team that, tending to be isolationist until very recently, was relatively new to the intricacies of warfare and foreign policy. A complex man, unusually willing to accept responsibility for failures, Curtin proved to be a strong leader. The strains of high office were to contribute to his early death in 1945.

Meanwhile, Australia was vulnerable. Barbed wire was quickly laid along strategic beaches where invaders might land. City lights, even car lights, were dimmed at night and big plate-glass windows were removed from city buildings because they would splinter in an air raid. Public hospitals in Sydney sent home many sick patients so that beds were ready for citizens who might be injured in air raids. Yet on Christmas Day, when the British base at Hong Kong suddenly fell to the Japanese, Bondi Beach was temporarily crowded with sun lovers.

In the next few months, checks were increasingly imposed on civilian life. As an 11-year-old schoolboy who eagerly helped to dig air-raid trenches in our Ballarat schoolyard, even I noticed some of the new regulations and “Do Not” signs. But they were not as liberty-crushing as those imposed on peacetime Victoria in the fight against the pandemic in the past fortnight.

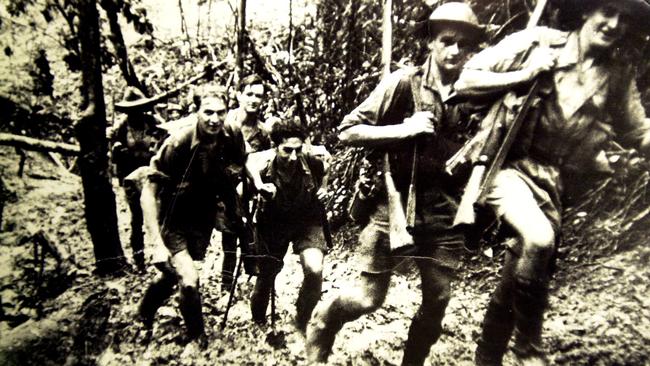

A Japanese army was moving so swiftly down the Malay Peninsula that the British, Indian and Australian forces barely had time to retreat through the jungles and rice paddies. Almost everywhere the Japanese were winning. They invaded the Dutch East Indies — the present Indonesia — on January 10, 1942. Nine days later they invaded British Burma. These two lands were vital producers of oil, a commodity urgently needed by Japan’s war machine.

Soon Australian soldiers fighting the German and Italian armies were recalled. Shipped through the Suez Canal to the Indian Ocean in the hope of saving one of these precious oil lands, they landed just in time to be captured; thousands died as prisoners of war.

The speed of Japan’s military advance across and along the equator continued to astonish. Its aircraft and submarines sped far ahead of its invading armies. Australia governed most of New Guinea but was unable to defend such a wide expanse of islands and sea. The naval and air base at Rabaul was bombed even before Burma was invaded. Rabaul fell before Singapore fell.

Finally, Singapore surrendered to the victorious Japanese army on February 15, 1942. That morning the senior Australian general, Gordon Bennett, left behind a blurred footprint. Bennett was a brave and much-decorated soldier of World War I, and his courage could not be faulted, but his decision to depart suddenly to advise Australia on how to thwart Japan’s fighting tactics was certainly controversial.

Today in the public eye the main heroes of the fighting in Southeast Asia are not soldiers but two prisoners of war who, as surgeons and leaders, selflessly looked after their fellow Australians. Edward “Weary” Dunlop and Albert Coates eventually were honoured at home by statues and knighthoods. Other heroes slipped from memory. Sister Vivian Bullwinkel, a young graduate from the hospital at Broken Hill, was a captive with 21 of her fellow nurses, each wearing the protective insignia of the Red Cross. On the edge of the ocean near Sumatra they were brutally massacred by Japanese troops. She was the sole survivor.

One remarkable event was known at the time to few Australians. Two nights after the fall of Singapore a huge Japanese submarine surfaced not far from the entrance to Sydney Harbour. On its deck the parts of a collapsible seaplane were quickly assembled, and the pilot and his observer flew over the darkened city, noting all the war vessels in the harbour before flying back to the submarine at dawn.

Next the submarine emerged within sight of the nation’s tallest lighthouse on King Island at the western end of Bass Strait. Again the seaplane was launched. On a cloudy day it flew low over the Laverton air force base and the Melbourne bayside suburbs of Altona, St Kilda and Frankston before disappearing down the bay and crossing Bass Strait to the waiting submarine. Hobart, two New Zealand ports and Fiji’s Suva also were spied on.

Why was the plane not pursued and destroyed? Puzzled spectators who saw it were slow to act. It was inconceivable that a small enemy plane could venture so far from the tropical theatres of war. Much of our knowledge of this big submarine comes from Sydney journalist David Jenkins who, researching in 1991 for his book Battle Surface!, talked in Tokyo with the seaplane pilot, Nobuo Fujita, then aged 80.

Four days after Singapore fell, the town and port of Darwin were bombed. Australian and US ships were sunk or damaged, and many civilians were killed. A second raid on the same day did more damage. Then the Japanese bombed the port of Broome, a haven for flying boats carrying refugees from the Dutch East Indies. Casualties were heavy; perhaps 80 people died. Townsville and other ports were bombed later, with little damage.

At first the wartime alliance with the US, ultimately so successful, was fragile. While Australia pleaded for more US troops and aircraft, its own war effort was criticised privately by military leaders in Washington. President Franklin Roosevelt privately complained that an Australian law prevented its conscripted soldiers, as distinct from its volunteers, from fighting far from home; yet US servicemen were duty-bound to fight wherever they were sent.

On the other hand Australians had been fighting for two years before the US entered the war. Indeed thousands of Australian airmen were fighting in defence of London or launching attacks on Germany. A surprising statistic of World War II is that three of every 10 Australians who died were airmen.

The two crucial naval battles in the Pacific War were the Coral Sea and Midway. Fought in May and June 1942, with aircraft carriers to the forefront, they marked the end of Japan’s supremacy on sea and air. But these momentous naval battles could not yet be seen as turning points in the war.

In the next 12 months, Australians were engaged in tense contests: the Battle of Milne Bay, the Kokoda Track, the war against dysentery and malaria in New Guinea, the silent entry of Japanese midget submarines into Sydney Harbour at night, and the outrageous sinking of the hospital ship Centaur near the Gold Coast. Even at the start of 1945 there was no assurance that the war would end that year, and no hint in Canberra that the war would be ended by nuclear weapons.

Eventually Australia as a nation learned more from adversity than from victory. The fear it might be invaded again some day by an Asian power dominated the first 30 post-war years. Australia must have a larger population, and so the ambitious European migration scheme was conducted with skill. Australia had to be powerful industrially, and it became by 1970 far more self-sufficient than it is now. And Australia still realised how much it needed a reliable and powerful ally. Today the nation’s wartime crisis has largely been forgotten. Its sobering events are probably taught to only a fraction of those school students old enough to understand them. Of the adult population in this migrant country, more than half possess little or no knowledge of Australia’s plight in 1941-42.

Yet if it is true that an awkward period of confrontation between China and the US has begun, and if it is true that Australia has no chance of standing aside, then the lessons of 1941-42 should be remembered.

In some circles today, there is more fear of a great-power war than in any year since the Cuban missile crisis of 1962, when the US came close to conflict with Russia. Several well-informed Australian observers liken the present situation in China’s seas to the perilous situation in Europe in the late 1930s. Scott Morrison has spoken about “the radical uncertainty we face, eerily haunted by similar times many years ago in the 1930s”.

If Curtin and Lewis were alive today they might wonder whether the lesson of the war’s dark days had been temporarily overlooked. They would feel uneasy that Australia seemed — as far as we know — to be relying on new submarines to be built mainly in France, with a delivery date far into the future and a fuel that could be outdated. Yet maybe we, the public, as in 1941, are partly to blame. Re-arming disrupts the pleasures and plans of daily life. Moreover, for a nation to re-arm too vigorously and outspokenly could possibly increase the likelihood of a minor or major conflict.

Nevertheless, one thing is clear: democracies can often display dedication in fighting a war, once a war occurs, but still fall dangerously short when the time comes to prepare for tensions or even for a cold war.

One of Geoffrey Blainey’s books is A Short History of the Twentieth Century.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout