During the past seven days, eight-year-old Bundy Namarnyilk walked 30km across west Arnhem Land’s stone country.

With the bush as his classroom, he learned how to live off the land: to hunt and roast buffalo, catch fish and forage for bush herbs. Elders taught him to manage the land with fire and told him the stories behind the bim (rock art) scattered across their country.

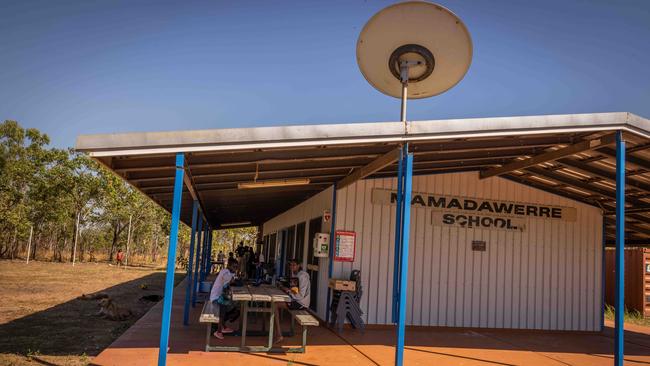

Today, Bundy is back in the regular classroom at Nawarddeken Academy at Mamadawerre, a remote homeland five hours’ drive from Darwin in the Northern Territory. He and his 14 classmates gather around a huge screen as their teacher calls up an image of the war in Ukraine.

After a discussion of current affairs, the class splits; Bundy and the other early primary kids practise digraphs and spelling, the older children create multimedia presentations on iPads.

The students are used to this merging of two worlds; the modern and the traditional. It’s in their schooling, their life, their language.

Their posters on the walls are evidence of it. They’ve pasted pictures of local wildlife, using their English and Kunwinjku names, into columns titled “safe” and “endangered”. Djobbo (northern quoll): endangered. Karnamarr (red-tail black cockatoo): safe. Malambibbi (Arnhem leaf-nosed bat): endangered.

Until recently, these children’s education was endangered, too. To save it, their community had to walk away from the NT government education system and create their own independent school.

Independent effort

In the Northern Territory independent community schooling is a different beast that often doesn’t rely on fees from parents.

Independent schools in the Northern Territory can attract significantly more direct school funding because most of the income comes from the federal government. Unlike NT public schools, independent schools receive almost all of the funding allocated to their students.

It also means federal funding isn’t affected by the NT’s attendance-based funding model and students receive what they’re entitled to under the Gonski funding model. Of 25 independent schools across the Territory, 10 were created for and by remote Indigenous communities, from Elcho Island on the coast of East Arnhem Land down to Yulara, near Uluru.

Association of Independent Schools NT executive director Cheryl Salter says the move to independent schooling often comes about because “communities wanted education for their kids and wanted to be at the core of it”.

“They wanted governance, input on culture and language. They wanted the traditional owners to be involved – that’s what independent schooling allows for,” she says.

Yipirinya, in Alice Springs, was the Territory’s first independent school – the result of town camp elders in the 1970s wanting to give their traditional languages and culture a place in their children’s education.

Nawarddeken Academy is the most recent, born out of community desire to see their children “walk in both worlds”.

“There were a lot of conversations with traditional owners, directors and elders. People were worried about all this intricate, deep, Indigenous, ecological, cultural, linguistic knowledge being lost,” Nawarddeken Academy chief executive and principal Olga Scholes says of their humble beginnings under a tarp at Kabulwarnamyo in the Warddeken Indigenous Protected Area in 2015.

“Community members and parents also recognised that alongside cultural knowledge, Western knowledge was vital for their children to have the same opportunities as other Australians.

“The value and the power comes from having the right balance of Bininj (Aboriginal) knowledge and Western knowledge, so that students have a sense of their own identity and understanding of the broader world.”

Kabulwarnamyo was registered as an independent school in 2019 and two years later two more schools in Warddeken followed at Manmoyi and Mamadawerre.

Before independence, there was no school for the children at Kabulwarnamyo, and Mamadawerre and Manmoyi were classified as Homeland Learning Centres, meaning they were classrooms attached to a hub school at Gunbalanya.

As with many of the Territory’s 31 HLCs, visits from qualified teachers were sporadic. Sometimes they went weeks without one. The infrastructure was ageing, too – at times, the HLC at Manmoyi didn’t have a working toilet for students.

Scholes says each of their three schools now has two registered teachers who work alongside two to three Indigenous teachers, and facilities have been upgraded. They have internet, technology and resources, all things that weren’t possible here before.

It’s too early for Nawarddeken Academy to report NAPLAN results, but the schools have some of the highest attendance rates in the Territory, averaging 89 per cent across Kabulwarnamyo, Manmoyi and Mamadawerre while students are in the community.

“So from one teacher once a week or once a fortnight to having four teachers, five days a week – it’s a huge difference,” Scholes says.

She says the community buy-in is what makes these independent schools work, and senior ranger and caretaker at Mamadawerre Rosemary Nabulwad agrees.

“It’s pretty exciting to have education full-time – we’d never had that before,” says Nabulwad, whose grandson attends the school at Mamadawerre.

“With teachers five days a week, now the kids want to get up in the morning.”

But the move to independence wasn’t an easy one.

Persistence pays off

When Terrah Guymala fronted up in Darwin demanding ministers give them a full-time school for the 25 children in his homeland of Manmoyi, he was surprised to receive a flat-out no, given how reasonable he thought the request was.

“We were saying, ‘Look, all Australian kids are having five-day education and us mob, we only got two, it’s not fair, wake up!’ ” Guymala says. “If you’re saying black people got poor education, then give us education.”

Looking out across the bush from the veranda of the Manmoyi ranger station, the former teacher and frontman of the band Nabarlek says it took five years of fighting to get five days of education a week for school-aged students at Manmoyi.

“We kept coming back saying: ‘Please, you should do your job,’ ” he says. “We kept coming back until they were really tired of seeing black faces.”

Registering an independent school is often a long and difficult process, with many claiming part of the problem is that registrar of non-government schools is supposed to be an independent position but they are employed by the NT Education Department.

Critics say the department is “resistant to independent schools” because “it takes away money from the Northern Territory government”.

“It’s not about kids, it’s about dollars,” says one former department staff member.

But persistence from Guymala and others paid off. He says people have moved back to Manmoyi as a result of Nawarddeken taking over the school and he knows his role in all of this goes beyond being an advocate and role model. As a senior ranger with Warddeken Land Management, he’s part of what keeps the whole community in motion.

It has cost about $2.5m to get the three Nawarddeken Academy schools up and running – they had to develop a local curriculum, upgrade facilities and support the schools until independent registration was complete.

Part of that money has come from philanthropic support from the Karrkad Kanjdji Trust, but a chunk of it has come from the income Warddeken’s fire management and carbon abatement program generates.

“When we started with land management we said, ‘This is the dream we’ve been dreaming,’ ” Guymala says as three sandy dogs curl up at his feet. “We got employment through land management, and now we will have employment through the school.”

With both employment and education in place, Guymala says the future is bright for the next generation here.

“Our kids, I want to see them here, in the office one day. Working. Typing. I want to see them writing letters to ministers. Or bringing in bird watchers,” he says.

“One day they’ll be (ranger) co-ordinators or they can be ecologists – whatever they want to be – but education is really important. We’re gonna have that. Because traditional way, we got that here. Western way, we want that, too.”

Model for others

A couple of hours away, up a red dirt road and through several river crossings, the Walaki people of Gamardi homelands have been watching Nawarddeken closely.

Sebastian Pascoe looks over at their rundown schoolroom. It has no power, making the room so hot and dark that lessons have to be held outside on the veranda.

He remembers a time, back in the 1990s, when he went to school here. There were about 18 children then, and a teacher lived in the community with them, became part of their family.

Now, a registered teacher turns up once a week, twice if they’re lucky, and the local assistant teacher is left to run classes alone the rest of the time.

When the assistant teacher is sick or away, they rely on someone to step in voluntarily.

Pascoe says it’s not good enough.

“My dream is to see (the children) grow up and graduate in front of us family, and get a job here in community,” he says.

He can’t see a way this can happen as things stand. He lives most of the time in Maningrida, 100km away, so his children can go to school full-time.

“I’m worried for them,” he says. “I’ve been (in Maningrida) too long. It’s time to come back. If we can have an independent school in Gamardi, we are all happy. This is what we’re hoping for. We want the world to see our culture.”

Garth Doolan from Gochan Jiny Jirra (also known as Cadel), about 45km out of Maningrida, shares Pascoe’s concerns. He says most children from Gochan Jiny Jirra are living in Maningrida at the moment because the school isn’t open often enough.

“Government want everyone to be in big communities, but in places like Maningrida you forget about who you are and what you stand for,” he says.

“There are issues with drugs and alcohol, the kids get bullied at school, the houses are overcrowded. It’s not easy to study.”

He says they want to be “out bush”, on the land they’re connected to, but they’re forced to choose between that and education.

Doolan is director of the newly formed Homeland Schools Company – a band of community members from all around Maningrida who are investigating whether they could follow in Nawarddeken’s footsteps and move away from government schooling.

Homeland Schools Company project officer and interim chief executive Shaun Ansell says the community felt they were given little choice.

“People are taking this path because it’s been demonstrated in the Warddeken region that it works,” he says. “Independent schooling is the only way to deliver actual community control and it’s the only way to secure resources anything close to what they’re entitled to under the Gonski funding model.”

Others have paid attention, too, with Warddeken community members fielding inquiries from several other communities keen for something better than the education on offer from the Territory government.

Yothu Yindi Foundation chief executive Denise Bowden says they followed in Warddeken’s wake to start Dhupuma Barker College in 2021.

-

“This drive for First Nations communities to have their own school and run it themselves, is gaining momentum, and I think that’s going to make a big difference”

-

The college is in Gunyangara, 14km from Nhulunbuy in northeast Arnhem Land, and the drive to build it came from the community’s belief that not acknowledging culture and language in the classroom was seeing their children left behind. Partnering with Sydney’s prestigious Barker College to create an independent bilingual school for kindergarten to year 6, Bowden says establishing a non-government school gave them flexibility that wasn’t otherwise an option.

“That independent model is the way to go as far as I’m concerned because you can do with it what your community wants.”

Former deputy chief executive of the NT education department Kevin Gillan is now an independent board member for Groote Eylandt and Bickerton Island Primary College Aboriginal Corporation, which is in the process of building an independent school to cater for Anindilyakwa children from years 3 to 6.

“(The NT government runs) everything on a template, a one-size-fits-all approach, but in the NT every remote community is a different nation with a different language,” Gillan says.

“What we really need is a place-based approach.”

He says Indigenous communities all over Australia are looking at independent school models because they aren’t satisfied with the quality of government education.

“The communities are unhappy with being part of a big bureaucracy which doesn’t have the resources to actually support a quality education for the children in those remote parts of Australia,” he says.

“I think this drive now for First Nations communities to have their own school and run it themselves, is gaining momentum, and I think that’s going to make a big difference.”

Protecting culture

Back at Mamadawerre, school is over for the day but the students are keen to continue learning. The whole class treks to the other end of the small homeland, where local rangers are setting a croc trap in the billabong.

“The biggest ginga (crocodile) is very clever,” Nabulwad tells them. “She’s been trying to get a dingo.”

The students have been learning about predators and prey, both in the regular classroom and in their bush classroom.

When the rangers trap a croc, it’ll be turned into a biology lesson about the prehistoric reptile’s digestive system, one of the many ways Balanda (Western) and Binij knowledge are entwined.

These children learn all the names of a creature. Its Kunwinjku name: ginga. Its English name: crocodile. Its scientific name: crocodylus acutus.

A school has a huge job to do safeguarding its children’s education, but Nabulwad says by allowing kids to learn on country and with their culture embedded in the curriculum, it’s protecting something else, too.

“It’s our way of keeping knowledge for our kids so they know who belongs to this country,” she says.

“Kids in the future will take over calling up the ancestors.”

Kylie Stevenson, Caroline Graham and Tilda Colling are independent journalists working in the Northern Territory and Queensland. This project was supported by the Meta Public Interest Journalism Fund.

More Coverage

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout