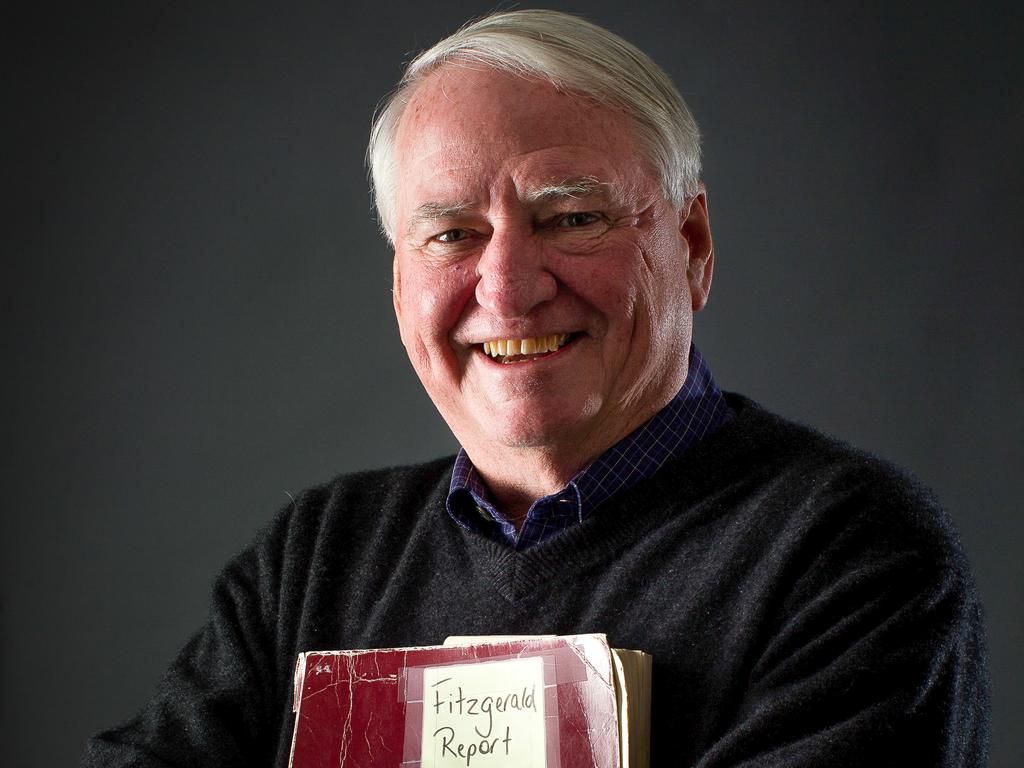

Tony Fitzgerald back to shine a light on Sunshine State

The Queensland graft buster didn’t take a narrow view of sleaze in the Bjelke-Petersen era and he shouldn’t hold back now.

Those who know the former judge and graft buster expressed surprise, to say the least, that he was prepared to step back into the ring after Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk turned to him to sort out the mess of the Crime and Corruption Commission in Queensland. But as Fitzgerald explained, it was a no-brainer even though he had studiously distanced himself from the public affairs of a state that arguably benefited more than any other from the disinfectant of sunlight he applied in the late 1980s.

“I was asked to do it and I couldn’t see any good reason to refuse,” he told this newspaper after being named co-chair of an eponymous Fitzgerald inquiry 2.0.

Still, to conflate the situation he confronted 35 years ago when the police were bent from the commissioner down and corruption reached all the way to the cabinet room under Joh Bjelke-Petersen would be a stretch for even Palaszczuk’s sternest critics.

The crisis she confronts is one of political integrity and accountability, compounded by wear and tear on the systems Fitzgerald devised to stop the rot re-emerging. This is where the CCC comes in.

No institution was more central to the process than the anti-corruption agency Fitzgerald envisaged in 1989 as a one-stop shop to enact and preserve the clean-up, combining investigative and intelligence functions to tackle organised crime as well as official misconduct by public servants, police and politicians, plus research, education and oversight of police reform. Its original name was the Criminal Justice Commission. Since then successive premiers have chopped and changed the model, dragging it some distance from the template.

How much of this was driven by need as opposed to craven political whim or even animus is open to debate. Just a few highlights of the serpentine saga: National Party premier Rob Borbidge in 1997, the year after Wayne Goss’s six-year reformist Labor government implodes, transfers the CJC’s major and organised crime responsibilities to a new body, the Queensland Crime Commission; with Labor returned to power, Peter Beattie in 2001 goes back to the drawing board with the renamed Crime and Misconduct Commission, restoring the crime functions but also charting a new approach. The CMC will not do as much of the legwork on investigating complaints; most will be referred back to the so-called originating agency – the police or government department concerned – to build capacity and resilience in the public sector.

Fast forward. Beattie has handed over to Anna Bligh. The newly merged Liberal National Party complains about the public service and judiciary being captured by Labor appointees. There’s talk the CMC is no longer the toothy watchdog it once was: “Cleared, Mate, Cleared,” the wags say.

Time for a new broom? Combative Campbell Newman cheerfully wields it after the LNP wins 78 of 89 state seats at the 2012 Queensland election. The CMC becomes the CCC and Newman changes its brief to refocus on organised crime.

He makes another big change, raising the bar for prosecution to corrupt conduct, broadly equivalent to the criminal standard. Then Newman loses stunningly in 2015 to the woman they didn’t see coming, Palaszczuk, the daughter of Goss-Beattie era MP Henry Palaszczuk and a minister under Bligh, who unwinds many of the LNP’s reforms.

Which leaves the organisation where it is today – more thoroughly sliced than salami, kicked around like a football, back to where it all started with Fitzgerald.

What to do? The ex-premiers all have their own ideas. They agree, though, that parliamentary oversight must improve. Beattie, who was founding chairman of the then CJC’s supervising committee of MPs, also argues that the head and commissioners of the CCC be appointed by an outside panel – say, the chief justice, president of the Court of Appeal and Speaker of parliament – from a pool of candidates nominated by the attorney-general in consultation with the leader of the opposition. “This puts the commissioners and chair above politics and gives both sides of politics a vested interest in the success of the CCC,” he says. Newman and former Nationals premier Russell Cooper back the plan in principle.

Borbidge thinks a statutory officeholder modelled on the federal Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security atop the nation’s six spy-related agencies should beef-up overwatch of the CCC in conjunction with a re-empowered parliamentary committee. Cooper says this also could provide an avenue of appeal to those aggrieved by a decision or adverse finding.

He speaks from bitter experience. Having lost to Goss in 1989 on the back of exposure by Fitzgerald of the systemic corruption that took root under Bjelke-Petersen, he was pinged alongside two Labor ministers and other MPs for misuse of travel entitlements by the newly constituted CJC. The accused miscreants weren’t named but enough detail was released for them to be identified. Cooper was adamant he had followed the guidelines, which were loose, but nevertheless resigned as opposition leader.

It set the scene for ongoing criticism from the conservative side: the CJC/CMC/CCC was obsessed with scoring cheap political points largely at their expense, not the main game – of going after organised crime, for example.

“My persecution was something a lot of people went through,” says Cooper, 81.

Labor wearily points to the toll in its ranks, including Beattie government minister Gordon Nuttall, jailed in 2009. Ahead of his resignation last week, CCC chairman Alan MacSporran had brought to book the corrupt ALP mayor of Ipswich, Paul Pisasale, despite his standing as one of the most popular local government leaders in the country.

A former crown prosecutor, MacSporran was appointed under Palaszczuk in 2015 and secured a follow-up term that would have taken him through to August next year. But he came a cropper when the CCC went after Logan City Council: the operation imploded, with the office of the state Director of Public Prosecutions dropping fraud charges against seven councillors. The all-party Parliamentary Crime and Corruption Committee ripped into the investigation, finding in December that MacSporran had not acted “independently and impartially”.

Rejecting this, the CCC boss said he had decided to quit over an irretrievable breakdown in his relationship with the parliamentary committee, not the criticism of his conduct.

No doubt it would suit Palaszczuk’s political interests were Fitzgerald and co-commissioner Alan Wilson, a former Supreme Court judge who headed an inquiry for her government into Newman’s contentious anti-bikie laws, to sheet home the responsibility to a CCC chairman gone rogue in MacSporran. The Premier shouldn’t hold her breath.

Fitzgerald’s landmark report in 1989 focused on the systemic causes of police and political corruption, not apportioning blame, and delivered a blueprint for reform that was embraced “lock, stock and barrel” by all sides of politics.

The real question is whether he pushes another Queensland government to widen his terms of reference concerning the CCC to get to the nub of the problems today.

Palaszczuk is under intensifying pressure over a series of integrity issues including a bizarre episode involving the wiping of a laptop held by Queensland integrity commissioner Nikola Stepanov, who quit a fortnight before MacSporran walked.

Stepanov maintains she tried to raise with the Department of Premier and Cabinet allegations of political interference with her office before she tendered her resignation on January 14. These are not matters unrelated to a now-rudderless CCC, which she also approached. The agency is investigating her formal complaint.

Fitzgerald didn’t take a narrow view of police sleaze in the Bjelke-Petersen era and he shouldn’t hold back now. We’ll see.

Tony Fitzgerald certainly has his work cut out. Again.