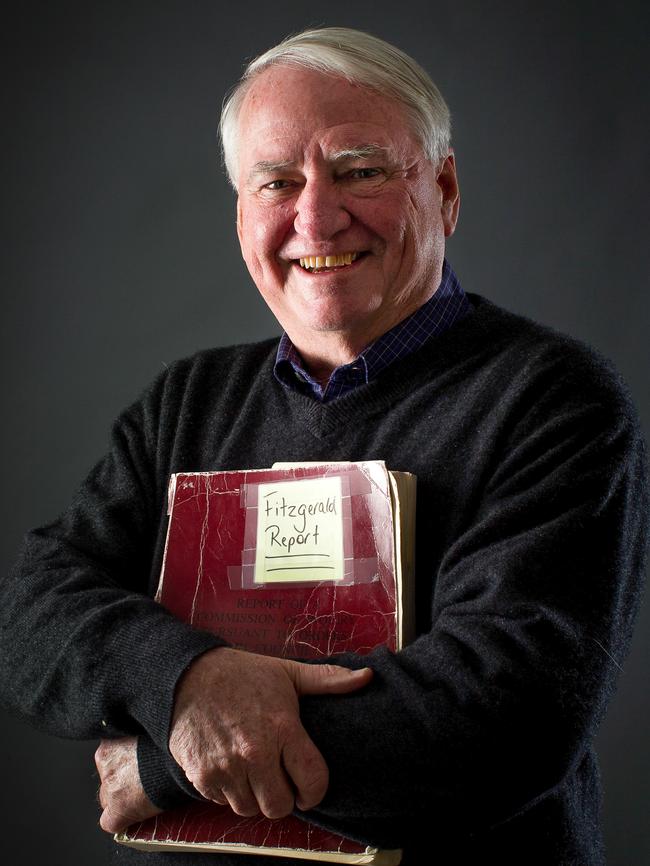

And just like that ... Tony Fitzgerald back in the political fray

The retired corruption buster’s re-entry into Queensland public life was typically audacious. Here he is, co-chair of a Fitzgerald 2.0 probe into the CCC.

Tony Fitzgerald’s re-entry into the bearpit of Queensland public life was typically audacious. After all these years and all the studied distance he put between his work and his home state, he has lost none of his capacity to surprise.

Because if there was one thing he was adamant about after literally writing the book three decades ago on how Queensland was to be governed, it was this: never again.

Mr Fitzgerald, 80, paid such a heavy personal price for heading the 1987-89 commission of inquiry that lifted the lid on the corruption of police and politicians in the so-called Moonlight State that he eventually moved to Sydney, became a judge there and on retiring from the bench refused to accept job offers in Brisbane.

Yet here he is, back in the fold, co-chair of a politically charged Fitzgerald 2.0 investigation into the Crime and Corruption Commission, successor to the watchdog organisation that was established on his recommendation in the 660-page report that became a blueprint for reforming governance and voting in Queensland.

“I was asked to do it and I couldn’t see any good reason to refuse,” a laconic Mr Fitzgerald told The Australian on Monday.

The approach to him was made at the instigation of Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk prior to Christmas, after she had perused but not read in detail a scathing parliamentary report into a series of failed prosecutions launched by the CCC into alleged local government corruption.

The agency’s chairman, Alan MacSporran, resigned last week.

Small wonder Ms Palaszczuk’s senior advisers were trumpeting Mr Fitzgerald’s recruitment as a “coup” for the Labor government.

She sorely needs a figure of his stature to sift through this mess. Mr MacSporran fell on his sword only days after Integrity Commissioner Nikola Stepanov quit after claims that senior public servants had gone behind her back to order the seizure and wiping of a laptop from her office. This happened while she was looking at allegations of illegal lobbying and high-level bullying.

Both Ms Palaszczuk and her office were adamant she had no personal contact with him, and the discussions on his appointment were conducted at arm’s length by officials. But the man she defeated seven years ago to the day to become premier, Campbell Newman, raised longstanding concern on the conservative side of politics about Mr Fitzgerald’s even-handedness.

The former LNP premier has neither forgotten nor forgiven Mr Fitzgerald’s devastating intervention in the 2015 election campaign. Attacking the then government’s record, Mr Fitzgerald had warned it would be “sheer folly” to vote for a party that “refused to accept there are limits on the proper exercise of democratic power”.

Mr Newman said on Monday: “I note for seven years we have heard not one peep from Mr Fitzgerald while the Labor Party has trashed the integrity measures that were in existence in this state. Not one peep, yet he was very vocal on occasion during our three-year term for far lesser transgressions as he saw it.”

The terms of reference for the six-month inquiry into the CCC to be chaired jointly by Mr Fitzgerald and retired Queensland Supreme Court judge Alan Wilson are based on a recommendation of the cross-party parliamentary crime and corruption commission committee that blasted Mr MacSporran for failing to ensure the agency acted “independently and impartially” in its pursuit of seven Logan City councillors and also raised concern about the culture of the organisation.

The new inquiry promises to be a showstopper, just as those 238 days of hearings were all those years ago under a younger and fresher-faced Mr Fitzgerald.

The experience was certainly searing for then QC, his wife, Kate, and their children, teenagers at the time. The family lived under the shadow of credible death threats.

Opening up in 2013 to The Weekend Australian Magazine, he described feeling like a “square peg in a round hole” in Brisbane more than a decade after the corruption inquiry, leaving him no alternative but to move away from the city he had grown up in.

“The background noise was always there, the level of hatred,” Mr Fitzgerald said. “One thing about the establishment – it never gives up, it’s never over.”

He emphatically rejected the talk among his detractors that he was a “Labor stooge”. By laying into the “establishment”, he was challenging the prevailing order – as with the cosy corruption under Joh Bjelke-Petersen – not elevating one political party over another. “Party politics leave me absolutely cold,” he said in 2013.

“I cannot believe that people yield up the ability to act in accordance with their conscience in order to act in accordance with the directions of the party.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout