This is where the boomers boom

Over the five years to June 2021 – including 15 months of the pandemic – we added 2.2 million net extra residents. Where have they all gone?

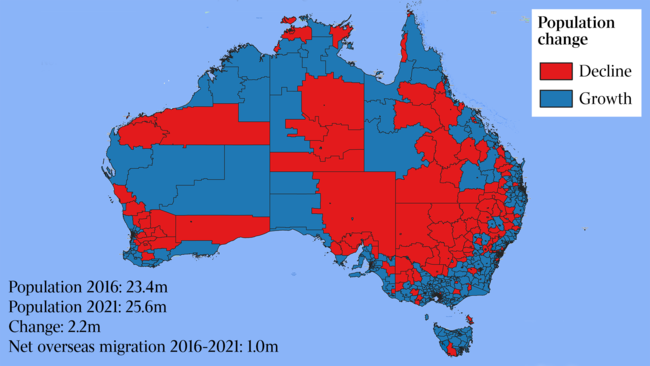

What have the Australian people done with the Australian continent between the past two Censuses? Over the five years to June 2021 – including 15 months of the pandemic – we added 2.2 million net extra residents; one million from overseas and the balance from natural increase.

The net migration figure (which includes overseas students) was perhaps 250,000 or so below trend due to Covid border closures. Averaged across five years, Australia added 440,000 annually with most growth loaded into the early years of this period.

So, where (and how) were these two million-plus net extra residents accommodated?

The answer is they mostly landed in our major gateway (capital) cities, but the story of the settlement of the Australian continent is far more complex; it involves flows from and to overseas; it includes the transfer of mostly young people from the regions to the cities; it comprises an outflow of retirees and “virus escapees” from the cities to what may be termed lifestyle zones; and it includes babies who tend to cluster in outer suburban Nappy Valleys.

The net effect of all these comings and goings is a map showing areas of growth and loss between 2016 and 2021.

About 70 per cent of the Australian nation lives in an area of population growth. This comprises the blue bits on the map; mostly capital cities and the lifestyle zones that fit between the Great Dividing Range and the Pacific Ocean. Others stretch outwards from the edges of each capital city.

We are an urban and a lifestyle-focused people. About seven million Australians currently live in mostly rural (and some urban) areas of population loss over the five years to 2021.

We are producing more agricultural (and mining) output than ever (and especially since the end of the drought), but we are doing so with less labour in the regions. And by the regions I mean the western slopes of the Great Divide right through to the wheatbelt of Western Australia.

Previous generations of Australians settled the margins of the interior; we are retreating. Indeed, these previous generations built mining and resources towns such as Paraburdoo, Tom Price, Karratha and even Broken Hill in the 19th century.

The Australians of the 21st century approach this issue differently; we’re still keen to capture the value of Australia’s resources but we have done so via the mining camp’s donga and the relatively new concept of FIFO workers. No need to live permanently in the interior, just fly in and fly out.

The diminution of population levels across the interior suggests farm aggregation: one farmer buying out the neighbour and the neighbour perhaps resettling to the Gold Coast. Another explanation is the advent of mechanisation and automation in farming processes prompting farmers to get big or sell out to a corporation or to a corporatising family farm enterprise.

In this demographic model, the towns of the interior subside. Youth sees opportunity not in the local community but in the jobs, education and training (and perhaps relationships) offered in the cities. The delivery of services forces aggregation: fewer specialty stores and more general, stores. Footy and netball teams are forced to merge with those of neighbouring (formerly rival) towns in order to survive. Religious ministers rotate between churches within their parish.

In the blue zones it’s a different story. More people creates more pressure for housing, for infrastructure; congestion ensues. Some flee the city, but rarely do they head to the red zone; mostly it is to the treechange and seachange territories that envelope the capitals and that follow the coast.

Australian towns that grew fastest between 2016 and 2021 comprise capital-city commuter towns – often in treechange or seachange locations – including Melton (up 27 per cent), Yanchep (up 26 per cent) and Warragul-Drouin (up 19 per cent).

Contracting towns were largely affected by the collapse of the mining boom such as Broken Hill down 3 per cent and Mt Isa also down 3 per cent.

The slow demographic diminution of communities in the red zone doesn’t so much apply to towns of more than 10,000 residents but rather to the smaller towns and villages that tend to be comprised of a few hundred as opposed to a few thousand residents.

The farmlands, too, are more sparsely settled today with fewer farm kids, with less itinerant labour in the regions, and with reduced services in local towns.

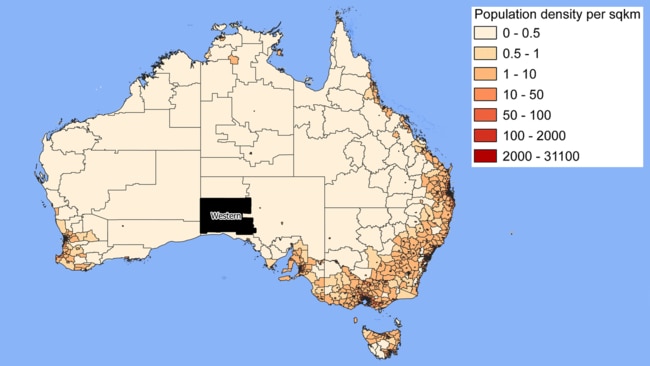

From a demographic perspective, Australia isn’t so much a vast continent as it is an archipelago (or maybe a comet) comprised of an eastern crescent (or boomerang, perhaps) and a series of trailing islands stretching off into a western slipstream.

The 2021 Census identifies our most sparsely populated community of just 144 local residents, mostly Indigenous Australians, which is located within a broader area of 168,000sq km in the far west of South Australia.

We are a land of contrasts. Australia comprises, and values, its rich mix of vast Los-Angelean-scaled cities and of similarly expansive traditional desert communities.

The most densely populated place in Australia, based on ABS geographies, is the northern part of the Melbourne CBD positioned between RMIT and Melbourne University. In this place, the largest non-Australian-born communities are (predominantly students) from China, Malaysia, India and Indonesia.

About 28 per cent of Australia’s resident population was born overseas. We have built a culture of absorbing immigrants on a vast scale since World War II. Mostly they settle in the biggest cities; this is unlikely to change in the 2020s as skilled migrants take up city-based, knowledge-worker jobs.

Another perspective of how the Australian nation, and people, changed between the past two Censuses is to consider the net difference in the age profile by single year of age.

The problem of the skills shortage is immediately evident: closed borders appear to have diminished the uni student and the early-20s cohort; Gen X contractions in the mid-50s and in the mid-40s are carry-throughs from reduced birthrates in the late 60s (ie, introduction of the pill) and from reduced immigration in the 70s (ie, high inflation and unemployment).

The surge into the 60s and the 70s reflects baby boomers retiring en masse. The 80+ cohort, not identified in this single-year dataset, jumped over 40 per cent over the five years to 2021. This is why the aged-care workforce is under severe stress. And the baby boomer cohort has yet to really impact this sector. This unstoppable demographic force will begin to arrive in aged care from say 2030 onwards or three elections hence.

But I see opportunity in this between-the-Censuses perspective. The millennial generation now straddling the 30s and with some actually crossing the 40 line (and into middle age) is shifting not so much into household formation but rather into the family-development stage of the life cycle.

Out with minimalist inner-city apartments, in with a requirement for accommodations with four bedrooms, two bathrooms, a back yard, a front garden as well as a Zoom room. By the middle of the 2020s, many millennials will be the parents of teenagers. Some of the city’s most recent escapees fled the virus for Australia’s lifestyle zones, included a smattering of 30-something millennials making choices about how and where they deliver their workplace value.

WFH is a tech-and-social movement that has arrived at precisely the right time for almost-middle-aged millennials looking for an alternative lifestyle and more affordable housing.

The problems with the skills shortage are in part exposed by the way Australia’s age cohorts contorted between the Censuses. A bucketload of baby boomers were always going to retire in the early 2020s; what was not countenanced was a two-year stay in the inflow of 20-somethings caused by the pandemic.

The bigger question for Australia is how competitive, or attractive, is our economy and our quality-of-life proposition to potential immigrants, students, skilled workers, backpackers, and high-flying corporate expats who can choose to work or study anywhere?

And even if we can rebuild the labour-pool inflows that are required by he post-pandemic economy, how can we deliver the right skills to the right communities across Australia?

Somehow, I think regional let alone remote Australia is likely to continue the process of adapting to a labour-scarce world: more machinery, more automation, more agtech and more ministers on rotation throughout their parish every Sunday.

And in some ways this is the essence of the Australian way of life: we respond and adapt the best we can to whatever is thrown at us.

Bernard Salt is executive director of The Demographics Group; data and research by Hari Hara Priya Kannan.