On the home front, it seems women have had enough

It’s the stuff that makes and breaks relationships. ‘Housework rejection’ appears to be taking hold — and boomer women are driving it.

It is the census question that asks about unpaid domestic work completed inside and outside the home.

The average Australian female (aged 15-plus) completes 87 minutes of unpaid domestic work every day, down four minutes over the five years to 2021. Males typically contribute 38 minutes, up one minute over the same time frame. There is no place in Australia where men, on average, do more unpaid domestic work (inside or outside) than women.

Places where this split is almost equitable tend to be inner-city suburbs such as Melbourne’s South Yarra (37:43 minutes) and Sydney’s Surry Hills (39:43 minutes). These communities have fewer households with children.

The completion of domestic chores rises and fall across the life cycle. Figures from the previous 2016 census show that unpaid domestic work peaks at age 38 for women and at age 43 for men. These peaks align with the arrival of young children.

Thereafter, as teenagers arrive in the family home, the parental contribution to unpaid domestic work subsides substantially for women and moderately for men. By age 49, women are doing 20 minutes less daily housework than a decade earlier. For men, the reduction is two minutes.

Could it be that teenagers do, in fact, contribute to household chores? Census figures suggest that the average 15-year-old girl is doing 18 minutes unpaid domestic work a day while boys at the same age are doing 14 minutes.

If so, the parental subsidence in daily minutes of housework completed in their late 40s and early 50s is indeed evidence of teenagers “stepping up”.

The other explanation is that managing a household with young kids (when parents are late 30s/early 40s) requires effort from both parents via unpaid housework. However, as kids become more self-sufficient parental housework duties, thankfully, start to ease.

But there is another unpaid-domestic-work peak later in life at age 69 for women and between 69 and 75 for men. This unpaid work does not include childcare such as minding grandchildren; that data is captured separately.

I suspect this later-life surge in unpaid housework relates to a nesting phase in the life cycle that coincides with the onset of retirement. This is the idea of keeping busy and of making one’s personal space clean and tidy – perhaps as a kind hedge against incapacitation setting in.

But not all is far from quiet on the home front. A comparison of unpaid minutes worked in 2021 with 2016 shows a distinct gender shift: women especially, it seems, have had enough.

There was an 18 per cent reduction in daily minutes allocated to domestic work for women aged 55-plus over this period. Men too pulled back on unpaid housework at this time, but this was by barely 5 per cent.

Maybe by 2021 baby boomer women were more likely to be working later in life, or perhaps they were simply more comfortable outsourcing some tasks. The impact of the pandemic, confining more Australians to the family home at the time the census was conducted, should have boosted, not diminished, time allocated to unpaid domestic work.

And if so the 2021 census results may be hiding a bigger, deeper, trend of “housework rejection” by a 55-plus cohort that is far more inclined to outsource domestic tasks that were once principally “done by mum”.

Mapping shows that Middle Australia typically allocates between five to 10 hours a week to unpaid domestic work, with women still doing twice as much as men. Remote communities tend to allocate up to five hours a week to domestic chores.

However, the mapping also reveals a correlation between what might be termed Australia’s houseproud hot spots and the retirement community. These hot spots comprise suburbs/regions where the time allocated by males and females to unpaid domestic work is 10-plus hours a week.

Bunnings and similar should do well in these places. Not just in providing all the accoutrement required for household cleaning, adornment and improvement including gardening, but also in being able to recruit older (experienced handyman-type) workers.

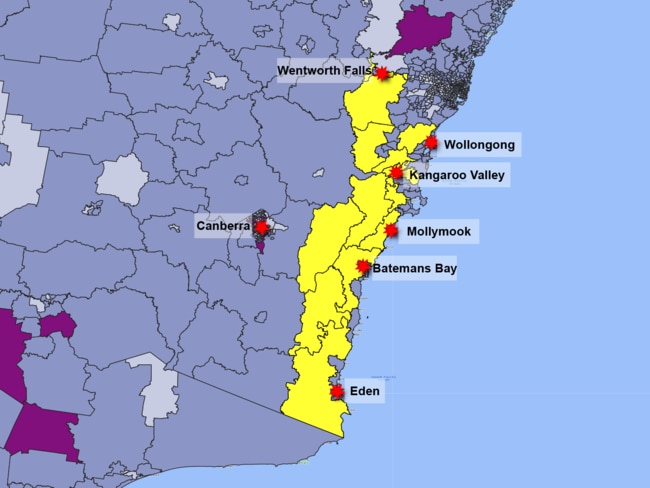

These houseproud hot spots surface on the West Australian coast between Denmark and Albany, on the tip of South Australia’s Yorke and Fleurieu peninsulas, across Victoria’s Surf and Bass coasts, at various points along the Queensland coast, but especially and almost fixatedly along the NSW south coast.

The high-water mark for the unpaid domestic work movement across the Australian continent isn’t so much the sea-change coast as it is the tree-change hinterland behind the sea-change coast. It isn’t for example Albany, WA, it is Albany Surrounds.

It isn’t Bateman’s Bay or Eden on the NSW south coast, it is the typically low-density acreage allotments that sit behind and above the sea-change coast. So, could it be that this simple, single question tucked away amid 60 other questions in the census has unlocked the mysteries, the passions, the priorities of the Australian people? I think so.

What is the quintessentially idyllic Australian lifestyle, especially for those aged in life’s later years, say over 55? For the well-to-do that could be the Gold Coast (Main Beach perhaps) or Noosa’s Little Cove or Byron’s Wategos Bay or the West’s Yallingup or Melbourne’s Portsea.

But for Middle Australia the aspiration is more commonly found in a lifestyle cocktail comprising tree-change space (with views) positioned within a 30-minute arc of the sea-change coast. This movement clearly reaches its geographic zenith along the NSW south coast.

The reason the south coast’s hinterland is Australia’s houseproud hot spot (along with equivalents in each state) is because low-density acreage requires maintenance. And men typically regard outside maintenance as their domain.

The scope to lift the male contribution to unpaid domestic work is greatest in places where projects outside the home are endless.

You can see men straining to add barely one minute a day to their household chores over the five years to 2021 but shift the home to the green and verdant hills behind Mollymook and these blokes morph into St DIY’s most devoted disciples.

For the better part of 20 years, the Australian lifestyle has been defined by the concepts of sea change and tree change. But what the 2021 census has revealed is what Australians really want is the best of both worlds and, it would seem, especially for older Australians, it is provided in places like the south coast’s hilltop houseproud blue-view corridor that threads along the Princes Highway between Sydney’s south and idyllic Eden.

Bernard Salt is executive director of The Demographics Group; data and research by Hari Hara Priya Kannan.

It is the stuff that makes and breaks relationships. It is a demographic metric that divides rigidly along gender lines. It rises and falls across the life cycle and throughout the Australian continent.