The US has the strongest incentive to prevent Taiwan from being captured by China

The exact sequence of escalating events, once a war begins, cannot easily be forecast. Would the US negotiate or would it retaliate by launching missiles on the Chinese ports and industrial towns opposite Taiwan?

The wars now waged in Ukraine and at half a dozen strategic strips of the Middle East have increased the public’s fear that a world war is possible. Similarly, China and the United States are said to be on the verge of another cold war which, this time, might boil over into a hot war. More likely – and such is the theme of a new book – is a lesser war fought around the island of Taiwan and rewarding a victorious China with virtual supremacy in the vastness of the western Pacific and its shores.

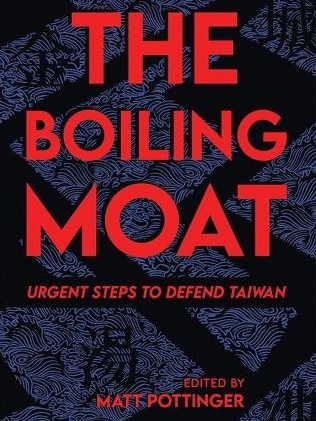

Even Australia might find itself in this new Chinese sphere of influence, a sphere at present dominated by the US. There are hints of such a fate in a significant book, The Boiling Moat, highly praised by Mike Pompeo, who was Donald Trump’s head of the CIA and secretary of state in Washington.

The book was initiated and edited by Matt Pottinger, who guided US strategy towards China in Trump’s first presidency. It is rare for a diplomat to record his own unique experience and muster the knowledge of other experts and then appeal convincingly to the public and politicians in his own nation.

Pottinger’s experience is exceptional. He operates in a domain traditionally presided over by high-ranking officers, recently retired. When young, he worked as a correspondent for The Wall Street Journal in China, where his knowledge of Mandarin sharpened his eye for news and opinions. Thinking that China was arming more rapidly than was the US, he sought military experience. With the help of a stern fitness adviser, he was commissioned as an officer in the Marines where he served one tour in Iraq and two in Afghanistan. That enabled him to gain novel perspectives on defence topics before serving as the expert on China in the Trump regime.

The book – of 281 pages – could have attracted the attention of even more strategy experts in the past month or two, but the presidential election has been all-absorbing. Exit polls on election day showed that in voters’ minds foreign policy was far behind the cost of living, the threats to democracy and other topics. Indeed the bitterness in American politics, and the possible absence of social cohesion for many months after the election, slightly increases the prospect that President Xi Jinping will seize these signs of weakness as an opportunity to undermine the US.

It was inconceivable, half a century ago, that China would become strong enough to threaten the US. In 1974, China was still weakened by the cultural revolution and the last years of stumbling Chairman Mao. It did not yet have a seat in the United Nations; its main foreign friend was little Albania; and though it was at last a nuclear power, its naval and air forces were relatively weak.

Then came the Chinese miracle. With visible and invisible help from the US, it enjoyed one of the major transformations in the history of the world; and judged by that longtime indicator of industrial progress – the annual output of iron and steel – it raced far ahead of every rival. A similar military “rejuvenation” – one of Xi’s favourite words – was also tackled vigorously by China.

The US is still the world’s wealthiest nation, and its standard of living is far above China’s. Defence, however, is not its high priority. In the era of president Ronald Reagan, when the Cold War was almost over, the US spent 6.8 per cent of its GDP on defence. Today it spends just over 3 per cent. American national security expert Kori Schake, in the magazine Foreign Affairs, confirms the dismal financial scene depicted in The Boiling Moat. In the past year, she explains, the US defence budget went backwards in real terms. Most of America’s major allies spend an even smaller percentage. What a boost to the confidence of President Xi – as if that all-powerful ruler needed one.

Xi lately has become a roaming shark in the South China and East China seas. He resembles President Vladimir Putin of Russia, who in 2022 displayed absurd overconfidence – parading his troops on the frontier for weeks before deciding to make a dash for the Ukraine capital city in the naive belief that he would earn a swift victory.

Under Xi, China has created new islands with airstrips and even baby fortresses in shallow seas which it does not own. It has expelled foreign boats from their traditional fishing seas and rammed Philippine supply vessels: Xi has defied an international court. On the eve of its 2024 election, Taiwan even detected in its waters a bullying parade of Chinese tugboats.

Pottinger does not call for the US to retaliate, but rather to strengthen its ability to defend itself. He believes that in the space of two years – if it is allowed two years by China – it can strengthen its defences. At present, the US in some defence categories has only enough ammunition to last a few weeks of heavy fighting. And yet – a lesson learned in the Cold War – “military hard power is the key to persuading China to refrain from setting off a geopolitical catastrophe over Taiwan”.

Should I be assessing this analysis? One chapter is spent in praising my book, The Causes of War, which was first published in 1973, read by Pottinger in 2019, and hailed in his private letter to me as “electrifying”. In this article I won’t discuss his generous analysis, and yet the other 12 chapters contain much knowledge that is new to me and to most potential readers.

Taiwan, the key topic of this book, often seems like a backwater. Small on the world map, it is not so by European standards: in area it is larger than Belgium and Macedonia. Nor is Taiwan’s population of 24 million so small by world standards: indeed it is almost equal to Australia’s. Notable too is Taiwan’s rising standard of living, now comparable to Japan’s. Above all, it is a young and thriving democracy.

Taiwan is just over half the size of Tasmania. The narrow seaway separating communist China from democratic Taiwan resembles our own Bass Strait, though our strait has rougher seas in a typical month. In calm weather, a small Chinese rowing boat can easily cross the strait to Taiwan.

Invasions by sea are extremely hazardous, even for modern armies. Taiwan’s leaders can expect weeks of bombardment if a Chinese seaborne invasion is under way. According to Ivan Kanapathy of Georgetown University, Taiwan “should be prepared to endure missile and bomb strikes, an enforced embargo, cyberattacks on critical infrastructure, disinformation campaigns, and other associated threats”. It is likely that the Chinese if they capture a long strip of coastline, will try to annex the inland mountains and gorges. There, however, the Taiwanese defenders have the advantage of fighting on their familiar home ground.

On the other hand, the Chinese might blockade Taiwan rather than invade it. Their submarines and destroyers could easily prevent any supply ship from reaching the island. This kind of slow victory would be aided by the fact that Taiwan normally has to import nearly all its coal, crude oil and liquefied natural gas. It also imports the food that supplies 63 per cent of its daily calories. Even if Taiwan’s government, expecting a blockade, had managed to stockpile energy and food, it might not withstand a blockade lasting for two months or more.

While the US might be inclined to go to war if Chinese forces did land on the coast of Taiwan, it might hesitate if the Chinese simply commenced a blockade at sea. But eventually the US would be forced to intervene. The strong eagle must protect its young. Such is the first commandment in any alliance worthy of the name.

Furthermore, the narrow Taiwan Strait – traditionally called the Formosa Strait – is one of the world’s busiest sea lanes. In some months the combined tonnage of foreign shipping using that strait is much larger than the tonnage passing through any European sea lane. A blockade by the Chinese navy, though aimed only against ships trying to sail to and from Taiwan, might unintentionally block Japanese and other ships. The danger is that the blockade might turn into a war involving other nations.

Taiwan owns – unknown to the general public – another asset. For perhaps the first time in modern history a small nation can briefly hold the whole world to ransom. Admittedly in the 20th century one Middle East nation rich in oil could ban exports, but other nations – also rich in oil – could circumvent the ban. In contrast only one nation in the world – Taiwan – is the king of semiconductor chips. It makes more than half of the world’s supply, as well as the overwhelming majority of the more sophisticated high chips.

The US has the strongest incentive to prevent Taiwan from being captured by China. The top-level computers in every large American city from Los Angeles to New York mostly depend on these Taiwanese-made chips. American industries such as chemicals, automobiles and munitions rely on the manufacturing skills of Taiwan. Everywhere, the office – in advanced nations it is probably a larger employer than the farm and factory combined – depends on the computer and its semiconductors. In November 2022, the chief executive of Citadel calculated that the GDP of the US would slip by 5 or even a startling 10 per cent “if we lose access to Taiwanese semiconductors”.

This single industry is so crucial to our lives – and even to warfare and surveillance – that it may, all in all, serve as an incentive for China or the US to initiate military actions. But it is not the only incentive.

The exact sequence of escalating events, once a war begins, cannot easily be forecast. Would the US negotiate or would it retaliate by launching missiles on the Chinese ports and industrial towns opposite Taiwan? Or would the American navy prove superior and quickly end a Chinese blockade or invasion? We are told the American attack submarines, each carrying more than 20 massive torpedoes, “are the foundation of US dominance in undersea warfare”.

The factors that extend and widen a war are familiar. Less familiar are the factors – economic, cultural, military and personal – which at the same time are promoting peace.

Though Taiwan has a larger population than Israel it cannot be expected to have the same fighting spirit. It must have allies. Therefore a combined warning by the allies is needed to dissuade Xi from attacking Taiwan. He will think again – he will hesitate to invade – if he receives a public declaration from the US, Japan, Australia and other allies that all together they will declare war on China, if necessary. The belief, however, of Pottinger’s historians and strategists is that the allies of the USA are, today, neither united enough nor determined enough.

They emphasise that even inside a particular nation the teamwork and the detailed defensive planning must begin before, not after, the war begins. Japan especially has yet to learn this lesson. With the fifth largest army in the world, its leaders even on their home islands do not always act as a team. When in March 2011 the tsunami hit the Honshu coast and even endangered the nuclear powerhouse, the various units of the armed forces failed to co-operate adequately after being summoned to the rescue. The dead and missing civilians exceeded 22,000.

One of the book’s authors is Yoji Koda, a former Japanese vice admiral, and he believes it is vital that Japan should be a firm ally of the US.

The book’s 17 authors, as a team, have wide personal experience of war. Among their predictions is that Chinese soldiers will entirely lack experience in combat, and that they initially must win command of air and sea in order to conquer Taiwan. On the other hand, the American defenders might soon suffer such a high percentage of deaths that public opinion will demand that the White House withdraw from the war.

Is Australia in danger in the long term if China tames Taiwan and becomes the great power in the northwest Pacific? Ross Babbage, the experienced Australian analyst in the team and an expert on strategy, sees danger ahead. He explains that Australia is not prepared for war. He argues that any conflict in the Taiwan Strait “would have huge ramifications for our continent”.

Professor Geoffrey Blainey’s Short History of the World has been an international best-selling book.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout