The truth is, China will stop at nothing until the West is lost

Beijing, 30 years ago — at the height of Australian delusions about China — used organised crime as one of the tools of state to try to force the US out of Asia. It’s been the plan all along.

The hostility between the Chinese Communist Party and the Morrison government intensified this week when Canberra joined the US in declaring a diplomatic boycott of next year’s Beijing Winter Olympics.

The China relationship can always get worse.

Here are three questions we have not answered, or even much asked: how long has Beijing been a geostrategic opponent of the US and Australia? What are Beijing’s ultimate strategic objectives? And what happens to the world if Beijing does take Taiwan?

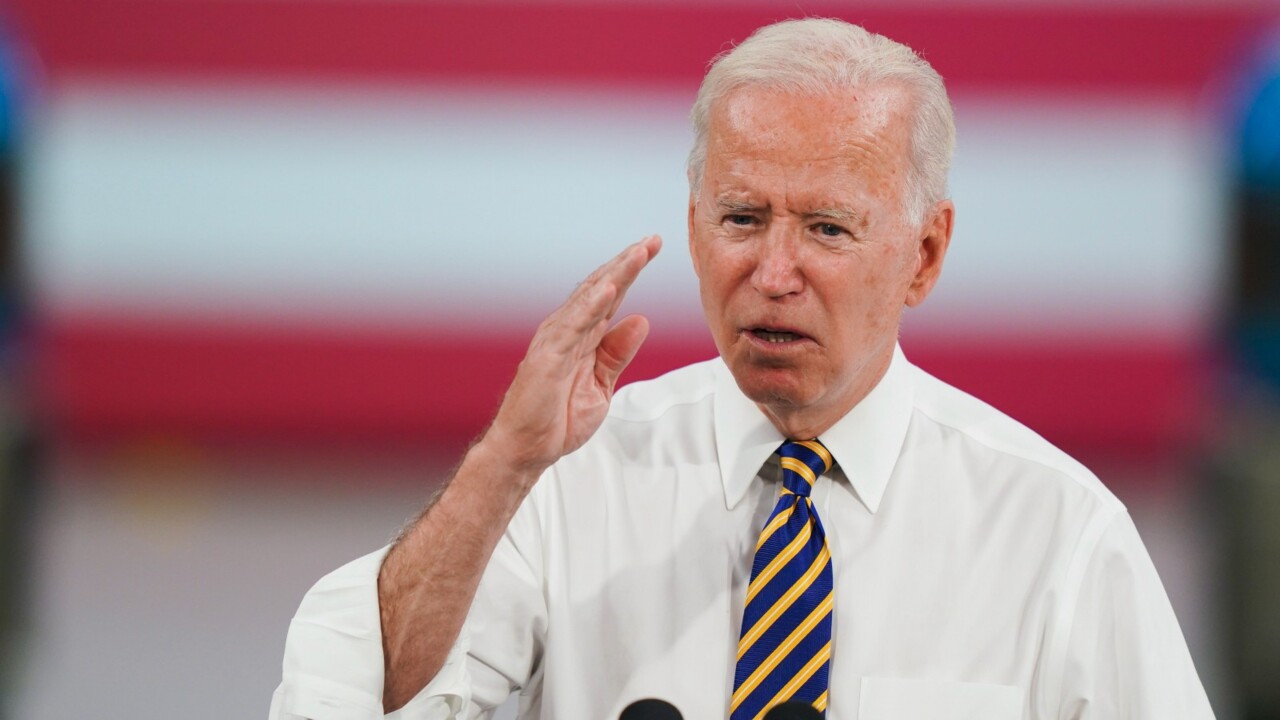

US President Joe Biden held a video summit with Russian President Vladimir Putin. The ever closer de facto alliance between Beijing and Moscow is acutely dangerous. Biden threatened fierce economic sanctions if Moscow invades Ukraine. But he also made it clear that the US would not intervene militarily.

This led so seasoned an observer as The Wall Street Journal’s Gerard Baker to conclude that the US would also never fight for Taiwan. This is a disastrous assessment. One hopes that Baker is wrong. It also shows he does not understand what is at stake in Taiwan.

Ukraine is a sovereign nation and deserves its freedom. But the US has never offered Ukraine a security guarantee. The implicit US security guarantee to Taiwan, by contrast, lies at the heart of the US position in Asia and the global rules-based order, such as it is.

If China takes Taiwan, all of Asia, indeed all of the world, is transformed and America cedes global dominance to China.

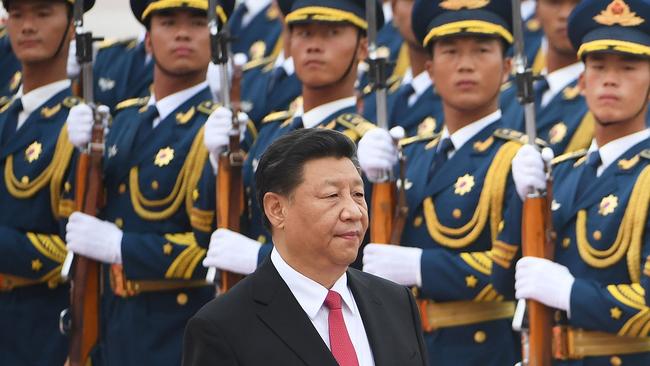

But first, how long has Beijing been determined to expel the US from Asia and establish regional dominance? When the Chinese Communist Party came to power in 1949, it was explicitly an enemy of the US, the Western alliance, and democracy in general. It went to war with the US in Korea in the 1950s. Throughout the 1960s, it gave financial, material and political support to deadly communist insurgencies throughout Southeast Asia and beyond.

In the 1970s, especially after 1979 under the newly pragmatic leadership of Deng Xiaoping, Beijing realised the weakness of its own economy. It had also concluded, long before, that its chief strategic enemy was the Soviet Union. The West was an enemy, but the Soviets had seriously considered nuclear war against China.

Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger saw a common interest between Washington and Beijing. They combined to counter Moscow. This meant the US did all in its power to bring China into the global system and open up trading opportunities for it. The emergence of the modern Chinese economy came about as a direct US strategic policy.

This led, however, to complete Western misreading of Chinese Communist Party internal politics, ideological direction and strategic purpose. No one got this more wrong than Australian elites, who simply refused to take the ideological (indeed, as I argue in my book Christians, the quasi-religious) beliefs of communism seriously. Such elites were years and years late recognising the purposes of modern Beijing policy and the real causes behind the seeming change to a much more aggressive posture.

Matt Pottinger, an acute analyst of modern China, was deputy national security adviser under Donald Trump. He resigned from the Trump White House in disgust after the January 6 assault on the congress. In Foreign Affairs, Pottinger argues that 30-odd years ago three events caused Beijing to conclude the US, rather than Moscow, had become its chief opponent.

These events were: the 1989 Tiananmen massacre, when the CCP recognised the challenge of Chinese democratic aspiration and crushed it ruthlessly; the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, which removed any threat from Moscow but also demonstrated to the CCP the folly of a communist regime embracing liberal reform; and the stunning ease of the US military victory in Iraq in 1991’s Operation Desert Storm, which convinced Beijing to abandon its old “people’s war” concepts and embark on intense technological modernisation for the military.

Since then, Beijing has systematically tried to undermine the US and its allies, although it cloaked its intentions for a long time while it caught up economically and technologically. This is not conjecture. It’s readily demonstrable.

One crucial episode was the end of the US military bases, Subic Bay and Clark Airfield in the Philippines in 1991. With the collapse of the Soviets, Washington no longer thought the bases necessary but was happy to keep them to reassure regional allies. The politics within the Philippines was complex and messy, but the Manila government negotiated an agreement with Washington to keep the bases. Then, by one vote, the Philippines Senate rejected the agreement.

Some time ago I met a former senior Philippines official, who had been at the very heart of his nation’s government. He told me the Beijing government had used Philippines organised crime, specifically ethnic Chinese crime networks, to mobilise vast amounts of money to make sure the Senate vote went against the bases. My Philippines contact also said a large share of the Philippines illegal drug trade originated in China.

These are explosive allegations and inherently difficult to check. The lead US negotiator on the US bases was Rich Armitage, who later became deputy secretary of state under Gorge W Bush. I put the scenario my Philippines contact outlined to him. Armitage replied: “It’s generally true. China threw a lot of money at the problem. They did not sway the (Philippines) government but had more success with the (Philippines) Senate. It was probably not determinate, but combined with drugs and crime made for an untidy mess.” I also asked Armitage whether there was a link between Philippines organised crime and China’s military, the PLA. He replied: “I cannot pin it on the PLA, but yes to the People’s Republic of China government.”

This shows Beijing, 30 years ago, at the height of Australian delusions about China, using organised crime as one of the tools of state to try to reduce the US presence in Asia. It is a doleful irony that if the US bases had continued in the Philippines, it is almost inconceivable Beijing would have been able to take control of the South China Sea.

Western crime-fighting and other agencies chart even now the connections between powerful organised crime networks in Southeast Asia and the Chinese state.

In Fentanyl Inc, journalist Ben Westhoff explores in detail how much of the illegal opioid drug trade in the West, and in other countries, originates in China.

The CCP has always seen the US and its allies, including independent democracies within Asia, as its enemy. For a time, it saw the Soviet Union as a more important enemy. It was shrewd in hiding its long-term strategic intent until it grew strong.

Nobody knows now what the limits are to the CCP’s long-term strategic ambitions. There is a robust and useful debate about if and when Beijing might move militarily to try to take Taiwan.

But let’s for the moment put that debate to one side and ask instead, what would the world look like if Beijing took Taiwan?

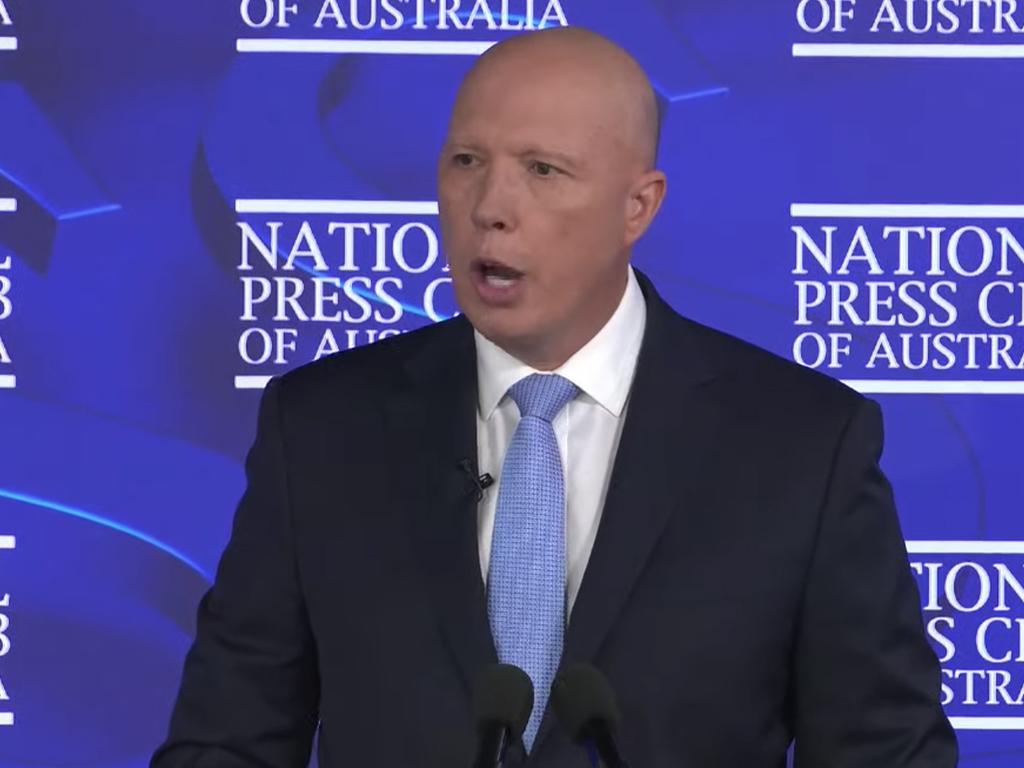

Defence Minister Peter Dutton is right to say that if Beijing invades Taiwan, it would also certainly take the Senkaku Islands, which currently belong to Japan.

But we can sketch out broader results. The US would cede its role as the dominant global power and become, at best, the second power after China. Taiwan once had its own nuclear weapons program. In the 1970s, it produced fuel to be used for nuclear weapons. If Taiwan had nuclear weapons today it would be secure from Chinese invasion. The US convinced Taiwan to give up that program and indeed to democratise.

Taiwan has kept every part of the bargain. It is an exemplary democracy, a brilliant economy and has a fine human rights record. If it fell to rule by the CCP, this would demonstrate that there is probably no Asian ally the US would fight for.

The traditional US position of strategic ambiguity over Taiwan was only to prevent Taiwan from provoking Beijing needlessly. In such a circumstance, the US would not feel bound to defend Taiwan. But in every other circumstance, it was always understood – and is provided for in the Taiwan Relations Act – that the US would help militarily in Taiwan’s defence.

The subjugation of Taiwan would fatally discredit, within Asia, democracy and alliance with the US. From Beijing’s point of view, it would have secured the greatest victory in the history of the Chinese nation and it would have done so on the back of trillions of dollars of investment in military hi-tech.

Beijing probably would not seek to establish a traditional empire, as Imperial Japan did. In Imperial Japan, the military became the government, whereas the Chinese military would remain subservient to the CCP. But Beijing could be expected to finalise every territorial dispute it has with every neighbour decisively in its own favour. This would be especially the case if the US failure in Taiwan had proceeded from internal polarisations and partial social breakdown. It’s easy to imagine the US strategically paralysed by a combination of the Steve Bannon/Rand Paul Republican isolationists with the anti-West Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez/Squad/Bernie Sanders isolationists of the Democratic Party.

In that case, every nation in Asia would have to come to terms with Chinese power. There would be appeasement parties in every state. Beijing would demand and likely achieve a kind of tributary state subservience from numerous Indo-China states.

It would also expand what is already a burgeoning international military base program.

What might this mean for Australia? Having Taiwan would transform Beijing’s military force projection capabilities and make it almost impossible for the US to operate in the Pacific. South Korea and Japan would either have to acquire nuclear weapons, or come to some uneasy and inevitably subservient modus vivendi with Beijing.

Almost inevitably, Beijing would acquire a South Pacific military base. Remember that Xi Jinping promised Barack Obama that Beijing would never militarise the islands it illegally occupied or created in the South China Sea, and then did just that.

In Vanuatu, or the Solomon Islands, or New Caledonia after the French, Beijing would ultimately secure a military base.

This might start out as a commercial shipping facility, or a logistics hub, or whatever. But the combination of Chinese money, military intimidation and the sense that the Chinese were winning while the US had lost, would most likely be enough to secure at least one South Pacific military base.

Within a few years, the Pentagon estimates, Beijing will have 1000 nuclear weapons and the ability to deliver them on hypersonic missiles. Beijing would certainly not start a nuclear war, but that level of nuclear weaponry would give it the ability to escalate any conventional conflict to nuclear threats quite early.

That would make it even more difficult for the US to intervene.

In 2003, then Chinese president Hu Jintao gave a bizarre speech in Australia in which he made the preposterous claim that Chinese sailors had discovered Australia, made frequent visits to the mainland, and established a thriving trade with Aborigines long before Europeans came here.

It is important that Chinese leaders have not subsequently repeated these bizarre fictions. But they are almost exactly the same as the kinds of claims Beijing makes to justify its occupation of the South China Sea.

If it ever felt it like it, Beijing, in the scenario sketched above, could cut off Australia’s trade through the South China Sea, blockade any of our ports, prevent movements in the South Pacific, decide to take possession of Australian offshore resources, etc. It would probably never do any of this because by then Australia would be trading with China on whatever terms it wanted and effectively obeying its political directions.

These are worst-case scenarios. Probably they will never come about. But they are all entirely possible in the event that the Chinese Communist Party establishes rule over Taiwan. And the truth is, we have absolutely no idea of whether a victorious Beijing would do these things or not.

More Coverage

Read related topics:China Ties