Tough talk on China no substitute for missing military capability

Our defence capability is pitiful and must be boosted with more weapons.

In Nelson’s time, the challenge was the relatively benign problem of Islamist terror and Middle East-based instability. In Dutton’s time, the challenge is China. Dutton’s speech was balanced, unanswerable in its logic, and nearly pitch-perfect in tone.

The one glaring gap is the lack of any new defence platforms in the works, a shocking weakness Dutton has inherited from a long line of ineffective defence ministers, working in effect at the direction of one of the great pacifist organisations in the world, the Australian Defence Department.

But Dutton is now bending every effort to change that. Australia needs him to succeed.

Dutton’s speech was also disciplined, observing the proper limits. There was no repeat of the threat that Australia would join the US in a war with China over Taiwan if one broke out.

Everyone knows Australia would join the Americans, but for a Defence Minister to say

so explicitly is needlessly provocative and leads inevitably to the series of dumb questions Dutton was asked – what military formations would we deploy etc.

Instead, Dutton stuck to the right themes – the overwhelming military danger posed by China’s militarisation, lack of transparency, explicit threats, and pattern of coercion. Dutton balanced this with his repeated desire to resume a normal relationship with Beijing if it will accommodate that, and Canberra’s overwhelming commitment to peace. But preserving that peace means reinforcing deterrence. That’s mainly a question for the Americans, but allies are important.

The government’s key weakness, which it should remedy before the election, is a complete lack of new defence platforms. We have, as Dutton convincingly outlined, reached

a stage of the greatest danger for Australia’s national security since the 1940s.

But we do not have one single, new defence platform to address this. That’s bizarre. The promise of nuclear-powered submarines in 20 years is all very well. But if the Morrison government is to be taken seriously, to meet the national need, it must address the defence force we will have over the next five to 10 years, as well as the one we might have in 20 or 30 years.

This has been a week of bewildering, multiple and often contradictory developments.

The Morrison government has rightly dispatched soldiers and police to stabilise the Solomon Islands. This shows the ongoing need for regular infantry. It’s all about helping the Solomon Islands, but even there the shadow of China looms large.

However, the new tanks which are costing billions of dollars, and the $30bn we plan to spend on heavy armour, can have absolutely no relevance to deployments like that. When questioned on why we are wasting so much money on irrelevant capabilities, Dutton replied in part that there could be another 9/11 and we might find ourselves again operating alongside coalition partners in different parts of the world.

That really confirms the wastefulness of this expenditure. Such deployments, like Iraq and Afghanistan, do not represent existential threats to Australia. Dutton rightly categorises Indo-Pacific developments as much greater threats. Therefore we should be prioritising expenditure that equips us for maritime contingencies.

The AUKUS agreement can have relevance. Oddly enough, AUKUS got its highest-level endorsement yet when China’s President Xi Jinping attacked it directly, though he didn’t mention it by name, in a speech to an ASEAN summit. If the Chinese President dislikes AUKUS that much, it must be worth something.

Similarly, the Biden administration announced former Defence Department under secretary Jim Miller as the co-ordinator of AUKUS initiatives. He will report directly to National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan. The Pentagon has set up a team of 30-odd officials to work on AUKUS.

The key point of AUKUS is to deliver nuclear-powered submarines to Australia. But it also involves enhanced US/UK/Australia co-operation over artificial intelligence, quantum computing, machine learning, cyber warfare, hypersonic weapons and undersea warfare. The Australian military was already co-operating very closely with the US, and to a lesser extent the Brits, on these.

However, the real promise of AUKUS, it is emerging, is not just that the three nations more seamlessly amalgamate their technology efforts, but that they work much more energetically to transfer often already commercialised technology breakthroughs into their respective militaries.

China has a systemic advantage over Western nations here, because every part of its international and domestic commercial effort, including vast technology research and application, is instantly available to and integrated with its military efforts. In the US, a number of hi-tech companies are very reluctant to work with the Pentagon.

And all militaries are themselves slow to change. At the start of World War I, many military commanders assured their political leaders that aircraft had no military application. This syndrome is evident in the fact that the Australian Defence Force still does not operate a single armed drone, yet drones have been around for decades and are proving highly influential if not decisive on foreign battlefields.

Here is the other critical consideration. All this hi-tech collaboration is of value to the Australian Defence Force only if it results in actual weapons coming into the Australian order of battle. That doesn’t mean concepts for weapons or plans for weapons or career-satisfying joint research projects. It means real, physical, actual weapons which we possess and which are capable of kinetic effect.

The government is very vulnerable on this score. Eight years of conservative government have proven just about as useless in terms of providing lethality, mass or war-fighting capability as did the previous six years of Labor government. Before Dutton, there was no sign anyone was even really aware of this.

The government’s provision of new capabilities in the next five to 10 years is still way too modest and Dutton needs to address this. One exception is that the government is moving significantly on cyber capabilities. These are important and difficult to publicise.

The government’s other main acquisition is new missiles. But here Defence is moving with its characteristic kabuki play, 100-years-of-solitude slowness. The government’s main hand-to-hand combat so far has not been with any foreign nation, but with its own defence organisation.

One big initiative the government has announced is to build a domestic missile manufacturing capability. This would add to the stock of missiles for the US alliance and it would give Australia the ability to accelerate missile production for ourselves. Missiles are in a sense a key asymmetric weapon. A small power can keep a big power at bay with them. Hezbollah, recently determined by the Australian government in its entirety to be a terrorist organisation, possesses 100,000 missiles and is close to an existential threat to Israel.

There is no class of missile which Australia possesses in large numbers, meaning we would run out of fire power five minutes after a conflict started.

Defence had been surveying the field in its normal leisurely manner and might well have come up with something in half a decade. The government has accelerated this and there could be an initial announcement about an industry partner, or perhaps two, by next week, or at least before the end of the year.

The government does not want a missile research program designed to bend the laws of the physical universe in several decades time. It wants an American company, or two, that makes missiles that we use right now, willing to join in establishing a manufacturing base in Australia.

No one can doubt the courage, or the magnificent record, of the Australians who wear their country’s uniform. But our ability to strike any enemy, to inflict any serious military harm, and to sustain any effort in combat against a military with first-world equipment is pitiful.

The government has announced the acquisition of three new classes of missiles: Tomahawk cruise missiles for the Air Warfare Destroyers and potentially the Collins subs; Long Range Anti-Ship Missiles (LRASMS) for the classic Hornets; and Joint Air-to-Surface Missiles (JASSMs) for the Super Hornets and Joint Strike Fighter F-35s.

I asked Defence whether any of these missiles had actually arrived yet, how many in total we were planning to get, and when they would arrive. The answer, delivered very politely, was: none of your business. This translates I think into none of them having arrived yet. We know the order of LRASMS is limited to 200 only because the US Defence Security Co-operation Agency approved the sale of up to 200 of them.

We have only 100 fast jets to defend the whole of Australia – 44 F-35s, 24 Super Hornets, 11 electronic warfare Growlers and a squadron of Classic Hornets, gradually being phased out.

Our navy is pitifully small. We have three modern warships, the AWDS. We have eight ANZAC frigates. These are already old, they are very small, about half the size of a contemporary frigate, and very lightly armed with only eight vertical launch cells.

And we have six ageing Collins subs. That’s it. That’s the totality of our fighting navy.

It also emerged recently that the government has decided not to build the big civil aid ship, which it’s going sail around the South Pacific, in Australia. Marise Payne, representing Defence in Senate Estimates, said this was because there was no room at any Australian shipyard.

This is an utterly ridiculous excuse and demonstrates the complete failure, so far, of our naval shipbuilding program to amount to anything. The submarines are delayed indefinitely. The future frigates, the Hunter class, are delayed by at least two years and no one knows when work will actually start on them as the design is not yet finished. We plan to build nine Hunters to replace the eight ANZAC frigates. But the first frigate does not arrive until 2033. We plan to build one every two years so the ninth should arrive in 2049.

And if we have so little confidence in Australian shipbuilding we won’t even build an aid vessel here, the idea we’re going to build nuclear submarines and power our defence force on the back of our manufacturing industry is ludicrous. It’s pure fantasy.

This is completely unacceptable for the Morrison government. This mess has been many years in the making but the government must address the defence force of the next five to 10 years, as well as the defence force of the 2040s and 2050s.

The frigates are a mess and it’s extremely unclear whether they will ever deliver. They certainly won’t deliver soon. Billions of dollars have just become available for defence purposes because of the collapse of the French submarine program.

The government must use this opportunity. Before the next election, the government should announce three big initiatives. First, the building of three new AWDs. We know how to build them now and they are real warships. Second, the acquisition of more fighting aircraft – more F35s, more Super Hornets and at least a squadron of the unmanned Loyal Wingmen. Third, we need to acquire large numbers of armed and lethal drones and undersea unmanned weapons.

Unless it does that, or something like it, the Morrison government will be finally marked as delivering great speeches on defence but not delivering the security that comes from genuine defence capability.

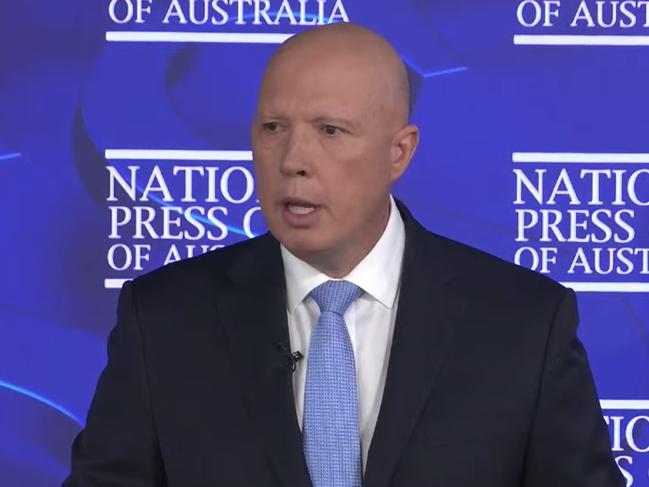

Defence Minister Peter Dutton delivered a historic speech to the National Press Club. For the first time since Brendan Nelson held the post under John Howard, a Defence Minister gave a speech which directly addressed the central strategic challenge and directly tied the purposes and structure of the defence force to that challenge.