The story of the wise men is an antidote to East-West division

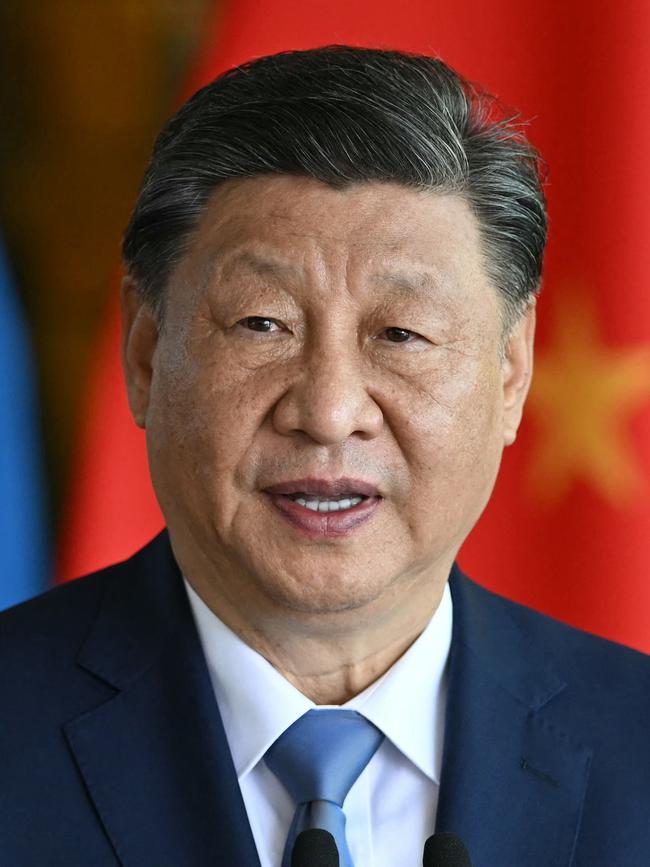

With Russia turning to China, North Korea and Iran on an axis of anti-Western animus, the globe has rarely been more sharply divided along an East-West fissure.

In the Gospel of St Matthew, and in this gospel alone, we hear the story of wise men from the East who are led by a guiding star in the desert sky to Bethlehem.

“On coming to the house, they saw the child with his mother Mary, and they bowed down and worshipped him,” recounts the evangelist.

“Then they opened their treasures and presented him with gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh.” Matthew calls the wise men Magi, the source of our “magic”, and it strikes the perfect note for a story richly embroidered with miracles – healings for the most part – building to the climactic death-defying magic act: Christ’s crucifixion, bodily resurrection and appearance to his disciples on a mountain in Galilee.

The journey of the Magi is worth recalling ahead of Christmas and the January 6 Feast of the Epiphany, its placeholder in the Christian calendar, for it speaks to the presence of the East in the West, the Orient within the Occident, of a God that unites us while civilisations divide us. With Russia taking a consciously eastward turn to join China, North Korea and Iran on an axis of anti-Western animus, the globe has never been more sharply divided along an East-West fissure.

The Magi story is an antidote to division, to schism. The wise men travel to Bethlehem to honour Christ, but the telling of the story in one of the synoptic gospels also honours the sage Magi and the legacy of eastern wisdom.

The Magi in Matthew’s gospel are more than exotic ornaments. The evil genius King Herod begs them to report back once they have seen the newborn Christ child but they manage to outwit him – well, they are wise! – and return “to their country by another route”. As envoys of a venerable yet heathen priestly tradition, they are instruments of prophecy favoured by God and symbols of an underlying human unity.

In time the story, which Mathew tells in a spare lapidary style frustratingly short on scene-building detail, took on new colours. The evangelist is notoriously vague on the number of Magi but Western tradition eventually settles on the number three – most probably to echo the gifts. The wise men are given a status upgrade and become kings. For its part, the house in which Jesus is born gets a status downgrade and becomes a rickety straw-strewn manger. Around the 8th century the Magi take on names: Balthazar, from Arabia, Melchior of Persia, and Gaspar king of India.

With their journey to the Levant to celebrate the birth of Christ we have something new in the history of monotheistic religion: the idea of foreign cultures united by a shared quest. The adoration of the Magi is a symbol of shared humanity bathed in a mystical light. The foreigners with their fancy dress and their exotic gifts are the first to recognise the child’s divinity, yet they don’t become followers, converts, devotees – they take their own path.

“Everything in history is expressed through symbols,” French-Lebanese author Amin Maalouf writes. “Greatness and humiliation, victory and defeat, happiness, prosperity, misery. And most of all identity.” Maalouf is an advocate for a common life – “at the end, we have one huge country, which is our planet” – anchored to an acknowledgment that each individual contains several identities. We are not reduced, as identity politics would have us believe, to one. The Magi story celebrates these possibilities.

It’s possible for East and West to coexist politically and culturally, just as elements from different cultures together shape an individual’s personality – for example, an Arab speaker in a Western country; an English speaker learning Japanese; a Catholic priest with a passion for Zen Buddhism. The last example is no hypothetical – in June I received an email from a high-ranking Jesuit and friend informing me: “I will be in Japan until the end of August … discovering the paths of Shugendo and visiting Mount Koya.”

Oxford historian Diarmaid MacCulloch, author of Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years, makes a related point obvious to anyone who has ever studied a map of the Levant and the eastern Mediterranean: “Christianity began as a religion of the Middle East and was as likely (in its first centuries) to move East as West.” In fact the early church spread first to Damascus and Antioch before turning west to Rome.

Rome continued to look east for spiritual inspiration, long after it had conquered the world. “We look to Rome for our own European cultural roots,” archaeologist Warwick Ball writes. “But Rome itself looked East.” And long after Rome fell and Florence and Venice inherited something of its greatness, the Italian states were still looking east.

In fact Matthew’s Magi story reaches its apotheosis in Renaissance Florence under the Medici.

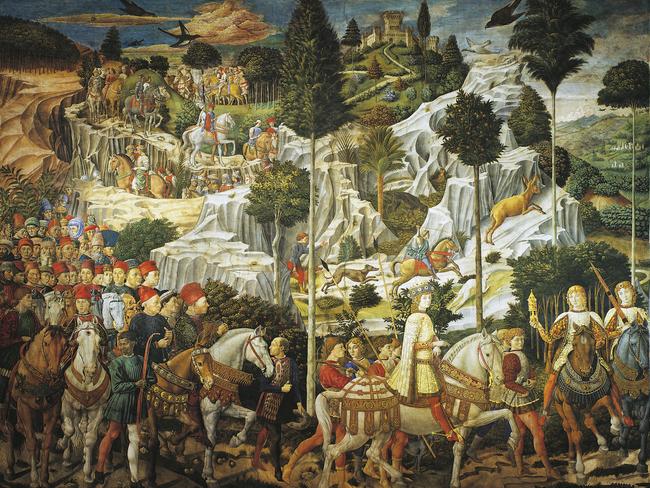

The walls of the Medici chapel on Via Larga are frescoed with a fabulously detailed Magi cavalcade as imagined by Benozzo Gozzoli, a work that riffs on Gentile da Fabriano’s blazing gold Adoration of the Magi, now in the Uffizi, and in turn anticipates two Magi scenes by Ghirlandaio and an unfinished panel by Leonardo (also in the Uffizi). In fact there’s barely a Quattrocento master who didn’t test himself on this theme.

Each year, at the festival of the Epiphany, a magnificent procession of the Magi wound through the streets of Florence – an elaborate piece of biblical cosplay supported with Medici funds.

The Medici’s enthusiasm for the Magi was anchored in a philosophical project sponsored by Cosimo the Elder, and maintained by Lorenzo the Magnificent, which was all about the unity of creeds and faiths.

The philosophers of the Medici circle were convinced that priests of ancient East – Magi, in effect – had foreshadowed the teachings of Moses and the philosophy of Plato and pointed towards the coming of Christ. They believed in ancient Egyptian prophecies from the dawn of time that predicted the ruin of paganism, the coming of Christ, the day of judgment, the resurrection and glory of the blessed, and the punishment of the damned.

It was in fact a grand delusion – the texts on which they were feasting, part of what scholars call the Corpus Hermeticum, were written after the birth of Christ, not before. But it doesn’t diminish the force or beauty of their vision, captured magnificently in Christian art, of a meeting of East and West.

There’s another less rosy reading of the Magi story and its remarkable afterlife. Perhaps the Magi in Matthew’s tale have journeyed west to honour the new religion, to pass the baton, to concede defeat. They have come to the site of a birth, to acknowledge a death – the death of paganism.

But the flourishing of the Magi theme in Christian art comes at a time when the East was a vital presence in everyday life – as a source of luxury and wealth, as the home of the Eastern Church, the source of ancient texts in Greek making their way to the West; and, in the more belligerent form of the Ottoman Empire, a growing menace. And that doesn’t square with a belief in the fading of the East. In fact it strongly supports the idea of a potent and beguiling Orient that stands apart from the West and yet is vitally a part of it.

The Magi story – or its poetic and artistic elaboration – is a celebration of the foreigner, of the other, and a vision of unity.

Luke Slattery is a journalist and writer. He is completing a book on Italian Renaissance philosopher Pico della Mirandola.