The story of Monte Toc: ‘Mountain that walks’ told villagers of the tragedy that was to come

Monte Toc rumbled on for years as engineers built the world’s tallest dam in Italy. Locals were nervous. Then their village was washed away.

Monte Toc speaks clearly. It always has. The reason locals call it the Walking Mountain is because, clear as a bell, it has constantly reminded them it was not to be fooled with. Great shards of rock and limestone have collapsed down its sides – centuries of scree building up like a giant stone lean-to as it gradually succumbs to an annual pummelling from snow, sleet, ice and rain.

“Toc” is a contraction of “patoc” which, in the local Friulian language of those in Italy’s northwest, translates as soggy.

Monte Toc walks and talks. And from 1960 onwards, its constant chatter bothered those living in the villages of its shadow – but far enough away, they always believed, to be safe from the mountainside as it shed its skin.

Rumbles in otherwise silent nights as another small avalanche of rocks slipped away were not uncommon, but once work started on a dam to stop the flow of the Piave River deep in the gorge below, things began to change.

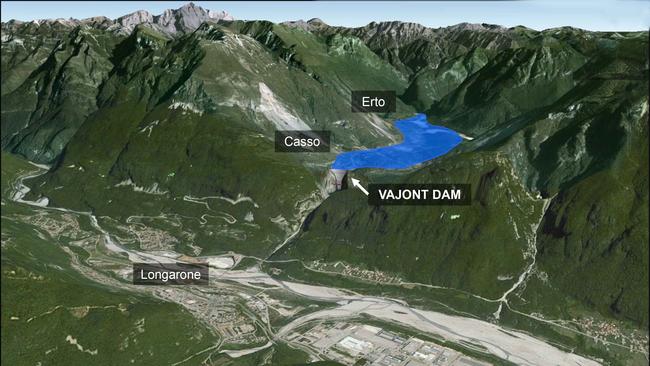

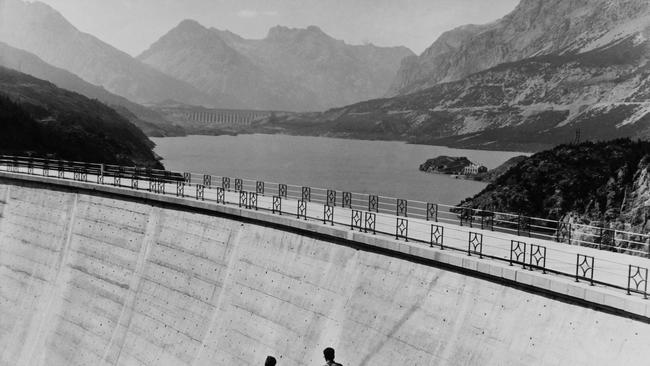

Plans for what would become the mighty Vajont Dam – with a wall rising 262m, the world’s tallest when it left the drawing board of Italy’s legendary dam-builder Carlo Semenza in 1957 – were first made in the 1920s.

The Italians were master dam builders and taming the almost indomitable forces that a dam would harness in that gorge – as Montes Borga, at 2734m, and Toc, at 1921m, loomed over it, shoulder to shoulder – was a challenge for which the rapidly industrialising nation was ready. It needed electricity; this was going to provide plenty.

But the plans coincided with the chaotic years of fascist dictator Benito Mussolini who, while expanding Italian industry, was more focused on adding to Italy’s African empire, subduing Libya and invading Ethiopia.

After Mussolini and defeat in World War II, Italy wasted no time in restarting its interrupted industrial miracle and plans for the Vajont were dusted off.

In 1957, the state-owned Adriatic Electric Company surveyed the gorge and decided it suitable for the arch-gravity dam that would curve upstream and transfer the fantastic pressure of the deep pond it would create and retain on to the rocky walls of the gorge that it spanned.

But from the outset problems with the stability of Monte Toc were obvious, at first with minor rocks slips that kept blocking the new roads contractors built to access the site. Experts brought in to resurvey the sites thought them fragile and unsuitable for a dam of this scale. A combination of pride and money kept it on track.

Just 20km away, a smaller project of almost identical construction was nearing completion. Cracks had appeared on the roads around the Pontesei Dam too, and on March 22, 1959, a half kilometre-wide chunk of rock, estimated at three million cubic metres fell into it, but did so slowly over the course of a few minutes. The Pontesei dam was well short of being full. Good thing, too. The landslide generated a wall of water estimated to have been more than 20m high that topped the dam wall and crashed down into the valley and killed a worker at the power station below whose body was never found.

People of the villages below the rising Vajont – Langarone, Pirago, Villanova, Rivalta and Fae – were nervous and demanded more detailed surveys be conducted. A model of the dam was built to determine how it would react to a landslide the magnitude of Pontesei’s. It was considered manageable. So it was full steam ahead, even though roads around the Vajont project cracked and in 1960 about 800,000 cubic metres of rock tumbled into the man-made lake. The dam’s owners decided to keep Vajont’s water level at 25m lower than its planned 262m peak – the Pontesei’s wave had been 20m.

By now the locals were on edge. They could hear and feel deep rumblings in the night and smaller landslides kept tripping into the deepening dam. In one incident, trees and rocks lost their footing and cascaded down Vajont’s slopes. They sought reassurance from Adriatic Electric Company engineers, who told them the landslides were manageable. One villager would tell a television crew years later that the engineers weren’t warning them what might happen, “but the mountain was”.

Sixty years ago this month, electricity generation in Italy was nationalised and ownership of the project passed to the National Electricity Board, known as ENEL. In the lead-up to its compulsory acquisition, the dam owners kept quiet about the problems with Vajont lest they undermine its sale price. Once nationalised, the world’s tallest dam became a symbol of Italian engineering and national pride and no one wanted to know about its problems. Journalists who reported on the possible dangers of the destabilised mountainside were reportedly mocked, harassed and even threatened.

Then it started to rain. The dam was rising by about 3cm a day and the mountains either side of Vajon were waterlogged – soggy, you might say. The new operators started to draw down water to relieve the pressure. Nonetheless, local mayors suggested their towns be evacuated, but Vajont’s bosses told villagers they were safe, that no landslide would create a wave big enough to overtop the dam.

Late on Wednesday, October 9, 1963, the village children were in bed contemplating the next day’s school. Most adults also were preparing to sleep, but a few were in the town’s bar watching Celtic play Real Madrid when a thunderous crack of biblical proportions announced disaster. It sounded like the earth had split. Part of it had.

Cleaved from the face of Monte Toc a 260 million-cubic-metre rockslide tumbled at 100km/h towards the lake and in 45 seconds filled it, catapulting rocks and trees almost 300m into the air, and creating a wave that roared back up the valley, and another that surged down to the Vajont Dam wall, which it cleared by an easy 100m.

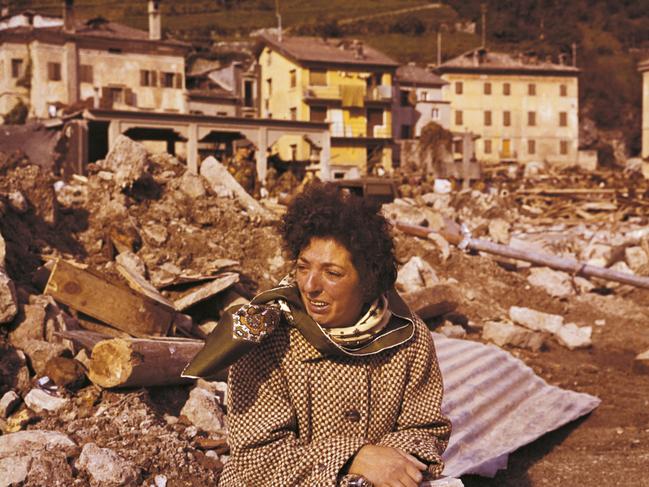

Ahead of it was pushed an explosively powerful body of air that punched between the gorge walls ahead of the megatsunami to come, demolishing the closest village, Langarone, with such force that houses exploded, cars became airborne and the locals’ clothes were blown from their bodies. The water arrived 30 seconds later crashing down from a terrific height and crushing anything left of the town which it then swept away in a tide of mud and debris.

A kilometre downstream the usually sleepy Piave river flowed furiously to a depth of 80m.

Langarone and its outlying villages were gone – 1328 people were believed to be in Langarone that night, 94 per cent of whom died, 460 of them children. Many bodies were never found. Most were never identified. In all, up to 3700 people were killed in the area. The toll reportedly included 54 dam workers and engineers who, believing some sort of event was likely that night, stayed on to monitor it. Remarkably, one survivor was Micaela Colletti, who was 12. She’d heard birds screeching moments before, an unusual time for them to be active.

And then: “I heard what I thought was a thunderclap,” she told a reporter soon after. “It was incredibly loud. My Granny came into the room and said she was going to close all the shutters because a storm was coming. At exactly the same moment all the lights went out, and I heard a sound, impossible to describe properly.”

She said the closest to it was that of metal shop shutters being slammed down, “but this was a million, a billion times worse”.

“I felt my bed collapsing, as if there was a hole opening up beneath me and an irresistible force dragging me out.”

The eruptive blast of wind carried her 350m and she landed in sludgy mud. All the houses were gone. She lost her grandmother, her mother, father and a sister. Only her father’s body was recovered and identified. When a rescuer found her in daylight she was mostly buried in black slime and “popped, like a bottle” when plucked out. He announced that he had found “another old one”.

It was immediately, and for years, portrayed as a natural event, an unforeseeable act of God. The Italian government offered little help while banning people from the site for three years. The survivors were few and soon dispersed as they looked to live and work elsewhere. Orphaned children were sent to live with relatives. But over the years, the townsfolk dribbled back and even started to rebuild on what remained of their land. Slowly a protest group formed and pressure was put on the government to pay damages for their ruined lives, and for changes that might help ensure it never happened to anyone else. Slowly, too, some lawyers pursued justice and six years later 11 public servants and electricity company executives faced charges of negligence and involuntary manslaughter. Three died awaiting trial, one taking his own life. Five were controversially acquitted, but three men, including the company president, the chairman of the Public Works Committee and an engineer were jailed for six years.

The Italian government was slower to consider compensation, but in 1999 agreed on the equivalent of $6bn to living survivors and the local municipalities. At that point, a government minister apologised. It had taken 37 years of lies to get there.

Carlo Semenza had died two years before the disaster, but he was posthumously cleared of responsibility. Indeed, his dam wall survived and today in the afternoon sun its pale face shines defiantly like a badge of honour. And it has become an unlikely tourist attraction with cyclists still making their way across its crest. But there is no water behind it, just the Piave trickling self-importantly below.

The victims of Vajont are remembered at a cemetery built a few kilometres south in the village of Fortogna in which many of the dead lay. There are also headstones for those never found: rows and rows of them like in a Flanders field.

A wall records the names and years of their birth, but not the date of their death. As if they needed to.

It was the night their love and laughter and even their land was washed away.

Underneath their names are these words:

At first the roar

And then the silence of death

But never the oblivion of memory

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout