Australian prosecutors are failing to secure court rulings that have enabled vulnerable witnesses to give critical evidence in sexual assault trials overseas.

Experts say traumatised survivors who struggle to describe verbally the abuse they suffered could be allowed to give evidence in writing by live-typing their answers to questions — a practice that is becoming increasingly common in the US and that is permissible under existing Australian laws.

In Australia the various states’ evidence and criminal procedure acts, as well as disability legislation, allow judges the discretion to permit witnesses to give evidence using alternative means of communication including typing, but no Australian prosecutor has yet used this power.

In 2015 a prosecutor in Vermont, Christina Rainville, secured a landmark court ruling that allowed her client to type answers during examination about repeated sexual abuse she endured in the family home. The complainant had a documented “expressive speech” disability and the trial resulted in a conviction.

Rainville spearheaded the practice of using disability laws to enable sexual assault victims, many of whom cannot verbalise their ordeals, to give evidence at trial using alternative means of communication.

“It’s a matter of community safety that we do what is necessary to take these people to trial,” she says. “Some of these witnesses may never be able to speak about their ordeals, and that’s OK, as long as they can communicate in a way that’s reliable. If you don’t bring a case to trial because it’s difficult because someone has to type their answers, you’re leaving that perpetrator free to continue to seek out other people and offend on them.”

While the development has taken hold in the US, Australian lawyers and legal officials are yet to adopt the practice, despite similar laws with the propensity to be applied in the same way.

Monash University associate professor of criminal law Jacqui Horan says Australian law could allow similar accommodations for a diagnosable disability. She says courts are becoming increasingly willing to accommodate disabilities in sexual assault trials.

“Now when you give evidence you can do it from another room via video, you can have a support dog at your feet,” she says. “There’s all sorts of accommodations that the courts have implemented in the last 10 years that just haven’t existed before.”

Read more: Virginia Tapscott’s incredible account of surviving child abuse

One of Australia’s leading criminal barristers, former prosecutor Margaret Cunneen SC, says she believes the practice of typing evidence could be applied only in rare cases.

“The complainant would have to be without the power of speech for some very well-established reason, like a medical diagnosis to say there is some sort of psychiatric illness causing the inability to speak,” Cunneen says. “I find it very unlikely that we go down this path except for a very extraordinary individual case. And if it comes from a psychiatric basis, then that might be something that affects credibility, too.”

Cunneen says a court order to type evidence during cross-examination also presents fairness issues. “If you miss the tone of voice and you miss the pauses and just how long people take to answer, that would work an unfairness on the accused person because the jury is told not only to listen to the evidence but to watch a complainant as she or he gives evidence in order to use their skills to try to determine whether the person is telling them the truth.”

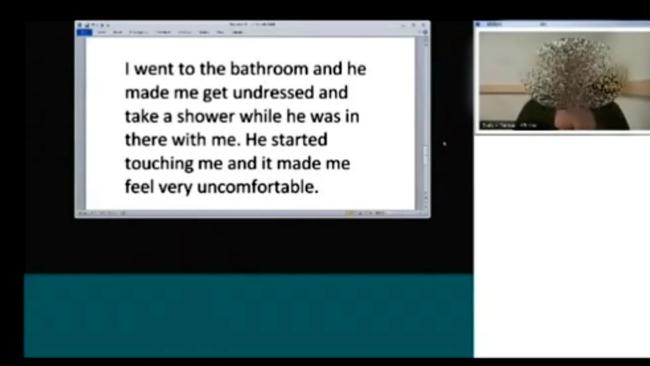

Regional NSW woman Fiona Weber (not her real name) is seeking the same accommodation secured for Rainville’s client back in 2015, which would permit her to give evidence in writing during examination. Despite six years of desensitisation therapy Weber remains non-verbal on the topic of sexual assault she endured at the hands of an uncle and her father beginning when she was just four years old.

In an interview with The Weekend Australian she responds to verbal questions by typing an account of the violent and sadistic sexual torture. “My Uncle had my face pushed into the pillow,” she types. “I remember him groaning and hitting me on the leg and saying, ‘You better not cry you piece of meat!’ It took everything I had in me not to cry. I don’t know if I passed out but I remember watching it happen to me as though I was not a part of my body. I honestly thought he was going to kill me this day.”

Weber is unable to speak about her ordeal because of a combination of personality and anxiety disorders resulting from the trauma. She suffers from selective mutism, a recognised psychiatric condition involving the consistent inability to speak when expected to during social interaction. When asked to describe the assaults, Weber is completely overwhelmed. Victims of sexual assault commonly cite an inability to verbalise their ordeal in the graphic detailed required for a courtroom as their reason for not pressing charges. Police advised Weber it would not be possible to press charges if she was unable to verbalise her experience.

The evidence in Weber’s file is otherwise compelling. Her police statement describes multiple harrowing accounts of incest rape that began before she started school. She still bears the marks of her abuse in the form of significant anal scarring, burns scars and chronic pain. “So many days going to school in pain, sick and sore from being raped just hours before,” she remembers.

“So many times wishing that this time they would actually kill me to end it.”

When Weber turned 15 the assaults ended. Twelve years later she gathered up the courage to report her ordeal to police. She spent countless hours in a quiet room at the local police station across a period of two years. She painstakingly communicated each excruciating detail in writing.

Rainville says selective muteness is a common challenge when prosecuting cases for victims of child sexual abuse.

“At trial, we recognise that, despite our best efforts, some of our clients will not be able to speak,” she says.

“If we have a diagnosis such as selective mutism or autism spectrum disorder, we will file a motion for accommodations under the Americans with Disabilities Act. These accommodations can include being permitted to testify outside the courtroom, write answers rather than speak them, or provide non-verbal answers such as nodding the head.”

In 2015 Rainville became the first prosecutor in the US to secure a court order that allowed a child sex abuse victim to communicate with examiners by typing into a computer screen showed to the court via video link. She has since delivered widespread training in the US legal sector to enable more vulnerable witnesses to give evidence in sexual abuse cases.

“I have done a tonne of training in the United States,” she says. “I really feel passionate about teaching people how to deal with these challenges in a trial and how to move forward and protect such vulnerable people in our community. It’s just not that hard to take these cases to trial with a little extra effort. Technology makes it really easy and it’s critically important.”

The legal landscape faced by sexual assault victims in Australia appears discouraging, with recent renewed efforts from within the NSW judicial system to dial back section 293 of the Criminal Procedure Act, the law designed to protect victims from slut-shaming by ruling out evidence relating to their sexual history. District Court judges have criticised the law as unjust in recent weeks and are pushing for a government review that would give them the ability to admit sexual history evidence in a broader range of circumstances.

The debate also rages on over gag laws to prevent victims from publicly disclosing their own abuse. Defence lawyers continue to gain access to confidential psychiatric records despite the implementation of the sexual assault communications privilege, a law introduced in the mid-1990s to protect victims’ privacy and designed to encourage victims to seek psychiatric support with the assurance that it wouldn’t be used against them later in court.

The data reflects an apparent inability of the judicial system to find ways to remedy an astonishingly low prosecution rate of sexual offences. Australia has failed to increase sexual assault prosecution rates despite an increase in cases going to trial in the past four years. The number of cases finalised in NSW has increased from 1381 in 2015 to 1851 cases last year, but the prosecution rate remained steady at 56 per cent for the last three years, according to Australian Bureau of Statistics criminal court data.

In the most recent Personal Safety Survey conducted by the ABS, 200,000 Australians self-reported being sexually assaulted in the past 12 months, meaning only a tiny fraction of offenders are ever convicted.

Rainville says legal practitioners will need training to better understand how to bring cases to trial that involve vulnerable witnesses to increase prosecution rates and to overcome misconceptions about trauma-related disability. “Tragically a lot of lawyers don’t understand, don’t know how to do it or don’t have the time to do it,” she says. “And then there is also this overarching fear that if you put the time into this in a criminal case, no one is going to believe a person with a disability anyway, and I think that’s just discriminatory thinking. In my experience it’s not true, the juries were very respectful and understanding when put on cases for people with disabilities. It’s a very different kind of feeling that you get from a jury, in a positive way.”

Clinical and forensic psychologist James Ogloff began working with sexual offenders and victims in 1985. He says increasing prosecuting rates is critical to deterring sexual offenders. “The currency of the perpetrator is secrecy and once that veil is lifted a lot happens,” he says. “It’s not uncommon in families for there to be experiences of victimisation even among siblings, but the siblings might not have told each other. In my experience with perpetrators and victims, somebody that has engaged in such horrific offending probably has done it to more people.”

Ogloff, also a lawyer and the director of the Centre for Forensic Behavioural Science at Swinburne University, says the ability to bring more cases to trial is important because perpetrators often plead guilty when historical sexual assault charges are laid.

“It’s not uncommon for perpetrators of incest offending to actually feel quite guilty later,” he says.

“When they’re offending they don’t feel guilty because they’re driven by their personal need for self-gratification. At the time they overcome any feelings of guilt by doing what we do whenever we do something bad; that is, we distort our thinking on that — often it’s blaming the victim or minimising the behaviour. But over time, particularly when they’re older that’s when sometimes they realise what they’ve done. Some perpetrators never get to this stage because they are more psychopathic, but I’d say most of the offenders I deal with, they realise that what they’ve done is bad and wrong.”

Cunneen, who shot to national fame leading the prosecution of the Skaf gang rapes that occurred in Sydney in 2000, says the Australian legal system is at the forefront of advances in prosecuting sexual assault. “The environment for a complainant has never been more receptive or encouraging,” she says. “The police are so much better trained and the prosecution is much more accepting of almost any case. So it’s very positive for genuine victims of sexual assault. I’m confident that NSW leads the way in this area for the training and accommodation for sexual assault victims and for sensitivity on the part of judges and barristers. There are many states in the US and some of them might have very activist courts. So I don’t really look to the United States as the leader.”

She says Australian courts are much better informed about the impacts of trauma than they once were. “Judges are very sensitive to the needs of victims now in a way that was never the case 30 years ago,” she says. “Barristers are not unpleasant or harassing in their cross-examination, they may be searching, they have to keep searching and be thorough, but they’re not rude, they’re not condescending, and judges wouldn’t tolerate it if they were.”

Weber has a teenage daughter, holds down a regular job and people know her as a jovial and caring woman. She was like this as a child too. She has kind, big eyes, dark eyelashes and olive skin. She has no substance abuse issues but experiences a strong desire to cut herself on difficult nights when her abusers terrorise her in her sleep.

Other than the scars, nothing about Fiona’s outward appearance and conduct would betray the true extent of the horrors she has lived through. This is typical of most survivors of abuse and assault. It’s almost impossible to know one when you meet them, but child protection group Bravehearts says, based on Australians’ own responses to ABS and other surveys, one in five children will experience sexual harm before they turn 18. In more than 90 per cent of cases the perpetrator is someone the child knows. And in most cases, nobody will ever be convicted.

If this story has raised issues for you, contact Lifeline on 131 114.

More Coverage

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout