My older sister used to help me hide from our step grandfather when he came to our beds in the night. I can remember bare feet scampering down moonlit hallways, huddling in a wardrobe and the screen door slamming when we ran outside into the darkness. It teeters on the edge of where my memories begin, but I can still see the shadow of him sitting by her bed. As she grew older she figured out we could evade him. At about seven years old she showed more courage than many adults I know.

I was too young for his liking for some years but eventually it was my turn. I was playing my Game Boy at the kitchen table at my Nan’s house. I had blonde hair cut in a short bob. I wore glasses and a yellow summer dress. He asked me to come for a cuddle, patting his lap in a gesture of welcome. I didn’t have a Dad. I thought maybe a cuddle from a man, any man, would be kind of like having a Dad.

His hands went straight for my knickers and his crusty old fingers hurt me. I did not have a word for what he was doing but he was breathing heavily. I didn’t want to get into trouble so I kept playing my Game Boy. I tried to press the buttons but my fingers wouldn’t work and my heart was hitting my ribs. After a while Nan walked past the kitchen window with a basket of washing from the line and saw us. She dropped the washing and threw open the kitchen door. She held up the offending arm of her second husband and slapped it. I knew something terrible had happened because Granddad got a smack. I didn’t hear what she said because I was trying to bolt and pull up my knickers at the same time.

I’m still running. My mind is always racing. I don’t know who to trust. I’m scared of the dark. Scared of being alone. It took me 24 years to work out why I harboured persistent undertones of being a disgusting person. I suppressed the memory expertly but the feelings remained no matter what I did. For a long time I did not identify what had happened as abuse, but my nervous system did. It’s been a long, hard lesson that the body never forgets. Once is enough.

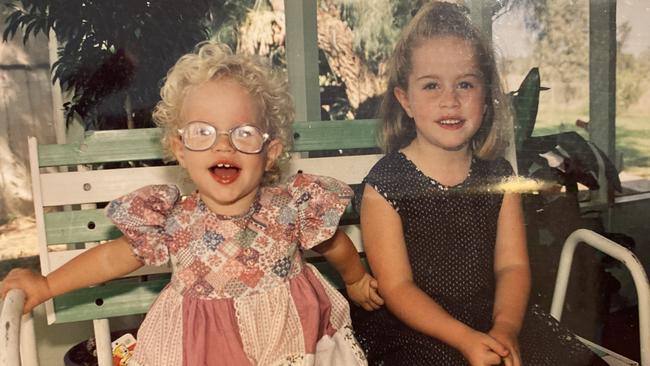

I’m writing this because my sister, Dr Alexandra Jane Tapp, died of a drug overdose in June. She was found alone in a motel room in Newcastle. That morning she was to be offered a position at a local equine veterinary practice. I was putting my daughter’s shoes on when I looked up to see my husband striding towards me, his face ashen. I think he was trying to tell me with his eyes so he didn’t have to stammer the words, “Alex is dead”.

It felt like something had been erased in me. I’ll forever be unbalanced. If my life was a book, someone just put a match to half of it. And that’s what she is now, ashes in a box. The trauma followed her until she finally succumbed in what the Coroner ruled was an accidental overdose. Two weeks before she died Alex told me another male relative had put a pillow over her face and raped her in the back of a truck when she was 18. Up until that moment I had loved and trusted that man with all my heart.

A gross betrayal by someone who should have tucked the blankets up around her chin. I can see why she was playing Russian roulette with methadone hits.

Everything I knew to be true was suddenly not. My mother’s words, ‘Careful who you put on a pedestal’, echoed around in my head. I wondered if life was one big fall from grace.

Alex was sexually abused repeatedly for years as a child and then re-victimised as an adult. Since her death I’ve learned that it’s not unusual for lightning to strike twice. An analysis by Swinburne University of Technology found that people who are abused as children are five times more likely than the general population to be assaulted again as an adult. The findings were drawn from a sample group of 2,759 Australian boys and girls who were medically confirmed to have been sexually abused between 1964 and 1995. The analysis found that they were more likely to be victimised again because their existing trauma predisposed them to substance abuse, making them more vulnerable to future sexual predators.

Alex grew up into a kind, successful, intelligent, broken young woman. People were drawn to her but Alex was never interested in the ‘cool’ girls or friends en masse. She nurtured close friendships with gentle souls, genuine and rare. Her career as an equine vet reached lofty heights, but behind closed doors she developed chronic multi-substance abuse and addiction. She self-harmed to cope with the pain that never seemed to leave. Psychiatrists diagnosed her with borderline personality disorder. She refused our pleas to attend rehabilitation clinics because she feared she would be deregistered. Her career became her livelihood and her whole sense of self. I’ve known for a while that she thought she’d rather die than lose that. She put on her public persona like she put on her clothes in the morning. She nursed a private hell. Her secrecy served as a breeding ground for shame and self-hatred.

I need to tell this story, in all its shocking ugliness, to elicit a reaction. I want people to say my dead sister’s name and to openly reject the whole spectrum of predatory sexual behaviours.

While judicial systems and law enforcement are busy playing catch-up and trying to work out how to protect people from sex offenders, we can all set a social standard that entirely rejects sexual violence in the conversations we have every day. We can simply tell the truth.

We can’t fix what we can’t see. I can’t remain invisible.

In doing this we destigmatise the victim and cultivate a culture where talking openly about sexual abuse becomes acceptable. We can help victims to feel safe to disclose and report. Keeping quiet creates the illusion that this kind of thing rarely happens and makes survivors feel alone. Secrecy is a form of tolerating these crimes and it effectively places an untold number of women, men and children at risk. When we omit these discussions, the crime and the victim become invisible. We can’t fix what we can’t see. I can’t remain invisible.

In high school I developed an eating disorder. I dabbled in bulimia. I can still remember the taste of a Golden Gaytime when it came back up. But mostly I purged myself through punishing exercise regimes. It’s a form of self harm which is a hallmark symptom of child sex abuse. I thought if I could be thin enough I might feel less disgusting. I also loved the control. It had been ripped from me in my Nan’s kitchen when I was four and every time I had to hide from my Granddad. I clawed the power back in any way I could. I’m taking the power back by writing this.

The trauma of sexual abuse and assault is devastating, lifelong and does not discriminate. It’s sickeningly pervasive. Sexual violence is happening on nearly every street, in every community, in every corner of the country and in every kind of family. The majority of perpetrators are known to the victim, whether children or adults. And as contradictory as it sounds, most sexual violence isn’t actually that violent. Psychological profiling of perpetrators indicates time and time again that the most common offenders only use as much force as necessary and rarely leave their victims visibly injured.

A stranger holding a woman at knifepoint: that’s our society’s common definition of rape. If you asked most victims and most perpetrators, they’d probably agree that anything less violent is not really rape; not really assault. This is wrong. And it is our silence that allows this myth to persist.

Sexual predators all over the country are probably sleeping well tonight, feeling safe in the knowledge that it’s highly unlikely they’ll ever be convicted. And they’re right to think this. One in three Australian women will experience physical or sexual violence but less than 20 per cent of incidents are reported to police. Just one in 10 reported cases of sexual assault results in a conviction. A fraction of convicted sex offenders receive a custodial sentence.

Perhaps more disturbing is that many offenders don’t even identify themselves as predators.

Victims also often don’t identify what happened as abuse or they blame themselves. For a long time I believed that I was some kind of sexual deviant who secretly liked to be fingered by old men. Why didn’t I just wriggle away and hop off my Grandad’s lap, I wondered. I honestly felt complicit until I let the memories surface enough to see it for what it was – a gross abuse of power. It also helped to learn about the freeze response. This is the body’s physiological response to dire threat, placing the more commonly understood ‘fight or flight’ response on hold and trapping a victim on the spot. Children are much more prone to the freeze response because they are more defenceless.

I know this happened. My fingers stopped working on the Game Boy and I felt like my brain was short circuiting.

In late high school, more memories began to surface. On one occasion I told my friends I had been ‘kiddy fiddled’. I think making it sound like a musical game made it easier to bear. Those girls still don’t know how important they were as an audience to one of my very first disclosures. They were genuine in their belief and their disgust that this had happened. They were also shocked. ’I just didn’t think things like this happened to people like you,’ they would say.

After every disclosure I reverted to a kind of memory suppression where I either pretended it didn’t happen to me or did not identify it as abuse. I didn’t want to be someone who had been sexually abused as a child, so I told myself I wasn’t. I didn’t want it to be part of the image I projected. I was worried people might think less of me or, worse, confirm my suspicions that I was disgusting.

That continued up until two years ago when I tried to explain to my husband what had happened to me as a child. I could hear myself speaking and I knew how bad it sounded. Because it is bad. At the time of this conversation my son was roughly the same age I would have been at the time of the abuse. I allowed myself to acknowledge the true extent of my vulnerability as a child. I felt the beginnings of the relief that comes with telling a long held secret. The untying of a knot.

I realised I needed to start speaking to my mum about what happened to us. I knew she could give me important closure that I didn’t realise I’d been seeking. I felt sick driving over to her house, ‘Who knew? Who knew about this?’ swirling around in my head until the words came tumbling out of my mouth in the middle of the kitchen. It was a relief to find out Mum didn’t know or suspect anything until the day Alex walked up to her and told her granddad was touching our private parts. Mum told me she immediately confronted Granddad and threatened to go to the police if he did it again. She took my sister and I to see a counsellor but Alex refused to speak. I told her I thought he should have gone to jail and we should never have had to see him again. Mum said she protected the wrong people and she was sorry, but it’s not really Mum who should be apologising. I’ll never get the apology I need because Granddad’s dead.

I needed that conversation. I can finally understand the complexity of the situation she faced. Not wanting to shatter the family by pressing charges and effectively going public to the whole community with the allegations. Not wanting the general public to know the most intimate details of what has gone on between her daughters’ legs. Not wanting to put a seven year old through court proceedings. What if he denied it in court and Alex wasn’t believed? What if Alex refused to speak on the witness stand? What if we resented her for telling everyone and hauling us through the ordeal of a trial?

I think in these situations people thought talking about it would increase the trauma by making us relive it, that talking about it would magnify the experience. But not talking about it made us more scared of what had happened. There was no debrief. It was an episode in our lives effectively left unresolved.

Mum hoped we were too young for any real damage to have been done and for a long time she thought we had dodged a bullet. We all pretended so well.

No one ever spoke of it again. We learned that when these things happen you don’t ever bring it up or ask questions about it. At his funeral everyone was talking about what a great guy he was. So I was deeply confused and thought maybe what had happened to us was acceptable.

In talking to Mum I realised she must also be seen as a victim of this man. He preyed on her children when he became too old to grope her. My Dad was killed in a car accident before I was born and Mum, a heavily pregnant widow, moved in with my Nan for support. For my step grandfather to take advantage of this situation is beyond belief.

Mum hoped we were too young for any real damage to have been done and for a long time she thought we had dodged a bullet. We all pretended so well. Alex and I were excellent students, mostly well-behaved and appeared emotionally well adjusted. We enjoyed an affluent, stable and happy family life for the most part. But pretending is exhausting and in 2016 Mum found herself at Alex’s bedside in hospital while she recovered from an overdose. Alex told her it was because she had been abused as a child and raped by that male relative, whom I can’t identify for legal reasons, in her teens. She wanted to make herself sick so she didn’t have to go to a family wedding and see her rapist.

Two weeks before she died Alex robbed my medicine cabinet of every opioid in it. When I realised and confronted her about it she told me she took anything to dull the pain of being abused by people who should have loved and protected her. Her emotional distress was so profound and so prolonged it eventually manifested itself as physical pain. I feel like keeping secrets hasn’t ended well for the Tapp sisters. So I’m trying something else – I’m no longer keeping secrets to protect abusive men. The relief is immense. I’ve been holding my breath for 24 years.

Alex kept her abuse and the rape secret because she was protecting everyone else. “It will tear our family apart”, she told me in a text message. It was the same with Granddad. She didn’t tell mum about the molestation for years because she had desperately not wanted to get anyone into trouble, desperately not wanted to upset Nan and Mum. To the end, my sister could not bear the idea of inflicting pain on others.

She also kept the rape secret because of the fear of not being believed. She could not bear the idea that a small handful of the people she loved most would launch a campaign of vicious and public attacks on her character, which is what did eventually happen. She knew she could not endure the harrowing experience of being told she had deserved to be raped. I wish she could have known what I now know - that most people in our communities were ready to stand up alongside her and demand change. That people believe her. That people understand victims do not fabricate reports of abuse and assault because why would someone voluntarily subject themselves to vicious and public attacks on their character. Why would someone voluntarily endure the harrowing experience of not being believed and to be told they deserved to be raped. Fabricating a story of this nature is downright stupid. My sister was not stupid. And she certainly wouldn’t have subjected herself to this kind of scrutiny under false pretences.

I wish she could have witnessed the uprising. The people who have called, messaged and written letters to tell us that what we are doing is courageous and long overdue. Men and women of all ages and backgrounds. The pro bono lawyers who came to our aid and the incredibly generous donations to organisations that fight sexual violence. It has come from unexpected places and carried me along on days when I felt I might lie down and not get back up. People know that what has happened, and continues to happen, is wrong. They know it’s time to tell the truth.

Mum reported the rape of my sister to the same policeman who turned up in her garden on a sunny Friday afternoon to tell her her eldest daughter had passed away. I guess she was done with keeping secrets to protect abusive men. She couldn’t carry it a day longer. We could have left it at that, with a police report filed away in a cabinet gathering dust, but Mum and I made the decision to go public with everything.

We had our reservations about whether our conservative, rural community would be ready. We thought we could be ostracised. But we knew one had already gotten away and we couldn’t let a second man get away with a horrific abuse of power that comes from a place of entitlement and complete disregard for other human beings. When I relate the story to my children when they’re old enough, I have to be able to tell them that I did something. That I stood up for what was right and that I stood up for my sister. That I stood up for myself. I want them to know that even people who are deeply damaged can be courageous in their search for healing. That sometimes in life people will not like the truth when you tell it.

There are still people who think this should all be kept quiet. A small town lawyer making threatening phone calls to try and shut us up. Cherished family members who didn’t go to her funeral. Some people feel that the words are just too uncomfortable and yucky to be in the public discourse. Some people feel that talking about this now somehow sullies the memory of my sister, as if she was doing something wrong when she was molested. As if she is somehow to blame because a man decided to rape her. I can see how keeping quiet protects these men but I fail to see how it protects her memory. I think that if people know the truth it raises her up, to understand all she achieved despite what she endured for so long. The shame is not hers and the shame is not mine.

I wasn’t prepared for the lengths people would go to in an attempt to salvage the reputation of the perpetrators who live on and to protect their own self image in being associated with the perpetrator. They employ quite extraordinary narratives to excuse the most abhorrent acts. Most of us by now are familiar with the excuses about women asking to be raped by being drunk or flirting too much or being promiscuous. I have learned that people are very good at telling themselves a bedtime story they can live with – regardless of the truth. Nobody wants to believe abusive men have families and walk among us and nod hello in the street. Nobody wants to believe they are married to a rapist or caught the school bus with one or that their dear old Dad violated innocent children. Very few rapists admit to actually being one.

There is not an hour that goes past where I don’t think about the innocent family members whose lives are being turned upside down by the secrets of these men being made public. The ripple effect of rape allegations has been the one thing I agonise over the most. But I am not the cause of this devastation. The cause of this devastation is the moment the jeans were unzipped. The pain, in these instances, has been inflicted by one person and one person only. Anything other than this is pure blame shifting.

If one in three women have experienced sexual or physical violence, that’s a hell of a lot of perpetrators. Some of them are bound to be married, it’s just a numbers game. They will have kids and parents and siblings and cousins and people who love them. I’m sorry if this is you, but I’m not really the one who should be apologising. You must know that in the long run, keeping quiet protects no one.

But the people who understand the vital importance of supporting survivors who report sexual violence are well past critical mass. People have been steadfast and unwavering and I think it’s restoring my faith in humanity. I think I can trust again. A steady stream of disclosures from acquaintances and complete strangers to tell us we are not alone in our experience. It demonstrates that a departure from the archetypal monster rapist is happening. It seems we may have stopped looking for the rape monster and at last we might be able to focus our efforts on the real problem.

Most nights I bury my feelings in pages and pages of research about the impact of child sexual abuse and studies detailing why men rape and abuse women and girls. I’m elbow deep in theory about the social conditions that perpetuate these maladaptive behaviours and warped belief systems. I need answers. I need to make it stop. I feel like if I can understand what has happened, I’ll be less afraid of it. I’ll be able to prove to myself that there isn’t something wrong with me. That I’m not a disgusting person.

I need to know our abusers to be free of them. I cling to the science but information on the psychology of perpetrators of sexual violence is elusive. Exploring this dark corner of the human psyche has not been much of a priority up to this point. Usually any discussion of the psychology of the perpetrator is seen as a backward attempt to excuse the behaviour.

So instead we continue to pour most of our resources into understanding the psychology of the victim. Even scientific communities have a tendency to treat the victim like the problem. Research articles about victims are said to outnumber those about the perpetrators 10 to one. I’ve filled out too many psychological surveys to count and spent hours in therapy. I’ve been probed and prodded and medicated. I think I’ve been under the microscope long enough. It’s time our abusers were laid bare.

Psychologically profiling sexually violent offenders allows us to understand the making of the abuser at every point in their life. It helps us understand the cultural and social experiences that inform their warped belief systems. This knowledge is critical to undoing their destructive thought patterns and maladaptive behaviours, but also for how we prevent them in the first place. If we continue to dismiss the psychology of the offenders, their faces will remain in the shadows. Their victims will continue to pile up. Not understanding who sexual offenders and perpetrators of abuse really are and what motivates them means that cops, prosecutors and jury members are still out there looking for the lunatic raping women at knifepoint in a dark alley.

I have three children now. Every day my husband and I bear witness to the intergenerational devastation of sexual abuse and assault. I can see it in my son’s face when I fly into a rage over a spilt glass of water. The confusion and the fear. My son is fast becoming an emotional carbon copy of me so now he is mostly scared too. I can hear the kids fall silent in the back when I’m in the driver’s seat trying to breathe through the panic. The fear is bubbling up and spilling over into their lives too. Everything starts moving in slow motion and I think to myself, oh I see now. I can trace this moment all the way back to that man’s hands sliding into my knickers or the pillow over my sister’s beautiful face. A nervous system stuck in the moment.

In the weeks before she died I saw Alex sit with my dog who was having an anxiety attack about the roar of the lawnmower. She stroked his ears and spoke to him softly and I’ll never forget it. This incredibly gentle and smart woman had so much goodness for this world and now this image of her highlights the senselessness of this situation. The collective loss of so many women with so much to give. I’m determined for my sister to not just be ashes in a box. If I do nothing, I feel complicit in the continuation of sexual violence against women. Alex’s trauma rendered her unable to hold her abusers to account but I’m still here. I will speak because I am able.

Listen to My Sister's Secrets, the gripping new podcast from Virginia Tapscott and journalist Steve Jackson. My Sister's Secrets is available in the Podcasts section of The Australian's app or wherever you get your podcasts. Go to mysisterssecrets.com.au to find out more.

IF YOU NEED HELP, CONTACT

1800RESPECT (1800 737 732)

LIFELINE 131114

OURWATCH.ORG.AU