The resurrection of Richard Nixon was one of the miracles of politics

The criticism of the disgraced US leader never abated, but Richard Nixon rebuilt his reputation after Watergate as one of the world’s most insightful statesmen.

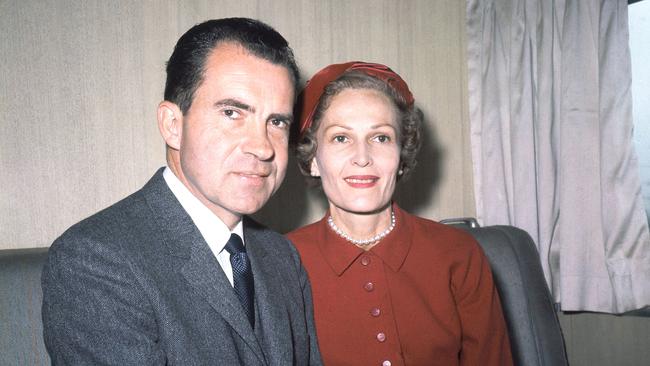

Thirty years ago, on June 26, 1993, former first lady Pat Nixon was buried on the grounds of the Richard Nixon Library in the president’s hometown, Yorba Linda, southeast of Los Angeles.

Her husband, the disgraced former president, sobbed in the company of his Republican successors Gerald Ford and Ronald Reagan and Southern Baptist evangelist Billy Graham. It was a unique display of sentiment by Nixon, who had repressed his emotions and navigated his life with lies ever since his mother caned him once for stealing biscuits.

An unidentified man stood beside him that afternoon. Very few recognised Arnold Hutschnecker. Nixon had long been a patient of his – a psychotherapist who for years had also treated actor Elizabeth Taylor. The Austrian-born expert had sought for four decades to deal with Nixon’s neuroses. In a controversial article in The New York Times in 1973, Hutschnecker had proposed that would-be political leaders in the US should subject themselves to a psychiatric assessment to gauge their fitness for the role.

Back then just a handful knew of Nixon’s secret shrink; those who did wondered if the 37th president of the US – their boss – would have passed muster.

Nixon battled to reconcile with his destiny. His knotty character was an unwieldy mix of obsessive ambition, insecurity, depression, racism and feelings of persecution. His endless lying was hardly eased by various medications and his drinking, and he was given to fits of explosive rage. A key element in who Nixon became might have resulted from that unresolved relationship with his mother. After his presidency, he admitted to a friend that although he deeply admired and loved his mother, she had never once kissed him.

His years as president are still fiercely debated and commonly receive harsh judgment.

In a C-SPAN survey of historians, Nixon in 2021 was rated 31st out of all US presidents. Yet he was rated by the University of California as probably the smartest Republican president in 50 years, with an IQ of 155.

Thirty years ago his second resurrection as the only man to resign from the Oval Office was almost complete. He had done it before. After 1960, when he narrowly lost the presidency to John Kennedy, Nixon set out to salvage what he could and rebuild his image with Americans. Second time around it took longer, but a famous front page of Newsweek in May 1986 declared: He’s Back.

Nonetheless, his detractors remained fierce. British-American commentator Christopher Hitchins said Nixon was unequivocally “the most scandalous and villainous Republican president of modern times” who turned his country into a “rogue state”. Hitchins wrote that Nixon was a “ruthless, paranoid and unstable leader who did not hesitate to break the laws of his own country in order to violate the neutrality, menace the territorial integrity or destabilise the internal affairs of other nations”.

In an obituary in Rolling Stone, persistent critic Hunter S. Thompson wrote: “Let there be no mistake in the history books … Richard Nixon was an evil man – evil in a way that only those who believe in the physical reality of the Devil can understand it. He was utterly without ethics or morals or any bedrock sense of decency. Nobody trusted him.”

Even Nixon’s remarkable post-presidential rebirth as a statesman of insight and achievement who wholly understood the subsurface nuances of the Chinese and Russians was attacked by Hitchins, Thompson and countless others.

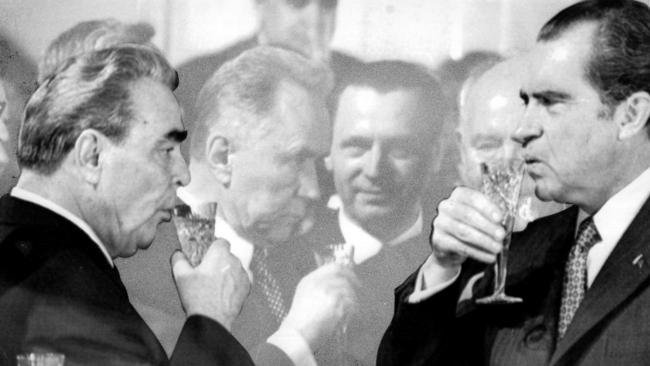

But Nixon’s legacy also has its supporters, a growing band of not-just-Americans prepared to overlook his lies and personal shortcomings and the big one – Watergate – to champion the risk-taking one-time commander-in-chief who spent more time negotiating with the Soviet Union’s hierarchy than all other US presidents combined.

He’d first gone to the Soviet Union as US vice-president in 1959 for the American National Exhibition in Moscow, where he toured with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev a mock-up of an affordable American suburban home with all its labour-saving devices. Moving from room to room, Nixon and Khrushchev exchanged barbs about each other’s technological advancements, encounters that became famous as the Kitchen Debate. It was awkward, but the men got on and the Soviet leader agreed to visit Washington.

Thirteen years later Nixon became the first US president to visit Moscow. He met Soviet premier Alexei Kosygin and agreed to the joint Apollo-Soyuz space mission that would surprise the world three years later. Those handshakes in the stratosphere are unthinkable today.

When Reagan as president sought to negotiate with Moscow on arms reduction and to schedule a summit on neutral territory between the cold warriors, he started as a backmarker. Preparing for a radio address in August 1984, Reagan joked before the microphones were turned on: “My fellow Americans, I’m pleased to tell you today that I’ve signed legislation that will outlaw Russia forever. We begin bombing in five minutes.”

This did not go down well in the Kremlin. The following year, when asked why it was taking so long to arrange such a date, Reagan responded: “My problem for the first few years was they kept dying on me,” a reference to the deaths of Soviet leaders Leonid Brezhnev (in 1982), Yuri Andropov (1984) and Kostantin Chernenko (1985).

Before the famous 1985 meeting between Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev in Geneva, Reagan sought advice from Nixon on what sort of man the Russian might be. Nixon said Gorbachev was smart and would have been elevated to leadership only because he was a hard man in whom the politburo had faith. But Nixon added: “We want peace. The Soviet Union needs peace.’’ The following year Nixon went to Moscow on what was ostensibly a private trip to meet Gorbachev, who was not given to meeting yesterday’s men of the West. This was a precursor to the Reykjavik summit at which US-Soviet talks would fail but at which the groundwork was laid for the historic agreement to limit nuclear arms.

Nixon’s deep connections, by then going back almost 30 years, meant he had 100 minutes in Gorbachev’s office. It was a “detailed and frank” talk about relations between the superpowers, according to the Soviet news agency.

Towards the end of Nixon’s active years he agreed to a now overlooked yet remarkable television interview with Harrison Salisbury, who had been The New York Times correspondent to Moscow in 1959 and knew of Nixon’s understanding of the Russians, his influence there and the grudging respect the Russians had for him.

Nixon explains the Russian character, warns against ever assuming they can be friends and talks of the risks for the West if it misunderstands this. He even describes the sort of leader who would be shaped to take advantage of this. Although he never lived to know or hear of Vladimir Putin, it is he Nixon so clearly describes.

Detente, he begins, is not about agreeing with Russia. It is agreeing that the countries have irreconcilable differences and then dealing with them, and of Russia understanding the West has powerful military forces and is prepared to use them if necessary.

Nixon warns that you cannot let the Russians believe there is profit in war. Clearly, in February last year, Putin thought he would profit from a short, sharp war against his much smaller neighbour. He miscalculated, but 345,000 have been killed or injured to prove him wrong. Nixon’s formula might have prevented this.

“They will lie, they will cheat, they will do anything to win,” he told Salisbury. But there was no alternative to negotiating with them. And they’d stick with a deal that was in their interests. “Russians and Americans can be friends, but the governments of US and Russia can never be friends because our goals are totally different.”

Later, in what may have been his last interview, and with the Cold War apparently over, the Soviet Union dismantled and the West victorious, Nixon warned the world again. “What has happened is that the communists have been defeated. But the ideas of freedom are now on trial,” he said.

“If they don’t work there will be a reversion, not to communism, which has failed, but what I call a new despotism, which would pose a mortal danger to the rest of the world because it would be infected by the virus of Russian imperialism which, of course, has been a characteristic of Russian foreign policy for centuries.”

He said those across the world who sought peace had a great stake in freedom succeeding in Russia.

“If it succeeds it will be an example for other to follow,” he said, mentioning China and other communist states. “If it fails, it means that the hardliners in China will get a new life. They will say: ‘It failed there, there is no reason for us to turn to democracy.’ ”

Then 26 days before he died, Nixon had a final opinion piece published in The New York Times. He had just returned from a final trip to Moscow. He wrote: “The independence of Ukraine is indispensable. A Russian-Ukrainian confrontation would make Bosnia look like a Sunday-school picnic.”

He wrote that any attempt to destabilise Ukraine, “to say nothing of outright aggression”, would have unimaginable repercussions for Russia’s relations with the West. “Ukrainian stability is in (our) the strategic interest (and should be a) security priority for the US.”

It was March 1994 and Putin was then the discredited – almost sacked – deputy head of the city administration in his hometown, St Petersburg. Nixon would never have heard of him.

But Putin is prosecuting the case Nixon foresaw.

Former Australian senator Stephen Loosley, a senior fellow at US Studies Centre, believes no one understood the Russians as astutely as Nixon and also praises farsighted building of bridges with China. He says the discredited former president also had an acute understanding of his nation and its elected representatives.

Nixon, a close friend of former Republican Senate leader Bob Dole, would, when returning to Washington from his California home, divert air force One to Kansas and pick up Dole and head east to the capital.

As they flew over the cities of Missouri, Illinois, Kentucky and West Virginia, Nixon would talk with deep knowledge about the local mayors and governors.

“He knew them all,” Loosley says. “And was a great student of history, but he was also quite a superb reader of other people; the tragedy is he could not read himself. And there were these very dark recesses in him. In public he could be quite reasonable and quite affable when he wanted to be, or when he needed to be, but that dark side of his personality was there.”

Loosley says Nixon’s hardline conservatism was to his advantage. “He had these impeccable anti-communist credentials. He said to Mao (Zedong) at one stage: ‘You are aware that I am anti-communist in my thinking’, and Mao said yes, he’s noticed. No Democrat could have done what he did.”

Loosley believes it is impossible to imagine the Reagan administration’s success in dealing with Gorbachev without Nixon’s era of detente.

“They certainly laid the foundations for dealing with the Soviets in terms of peaceful coexistence, negotiation of treaties and so on,” he says. “Reagan built on that by pushing the Soviets very hard, strategically and economically, to a point where they could not compete with the Americans.”

Loosley says on Ukraine Nixon would have met face-to-face and made it clear to Putin that NATO would respond. “He would have read the Russians particularly well, he would have read their weakness, particularly in terms of their military and politics, and in terms of their economic underpinning.”

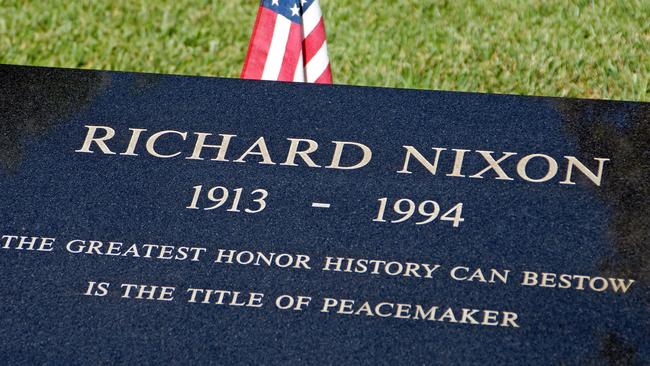

Both Richard and Pat Nixon died aged 81, the former president living 10 months longer than his much loved, long-suffering wife. As such he had the last word. Her headstone reads: Even when people can’t speak your language, they can tell if you have love in your heart. Next door his states: The greatest honor history can bestow is the title of peacemaker.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout