The nation’s invisible, and mostly unaccountable, central banker

The unfolding drama between Jim Chalmers and Michele Bullock is dominating public discussion. But the role of a pivotal player is being completely overlooked.

The federal Treasurer has said publicly that the RBA’s current 4.35 per cent cash rate is “smashing the economy”. But Bullock has stood her ground, reminding us that inflation is public enemy No.1.

This unfolding drama is dominating public discussion, but the role of a pivotal player – and the individual with the most influence over Chalmers and Bullock – is being completely overlooked: that of Treasury secretary Steven Kennedy.

Whenever and wherever the politics of monetary policy is discussed in this country, Kennedy is the nation’s invisible central banker. He is the Treasurer’s chief economic adviser and confidant.

At the same time, he is a full voting member of the RBA’s interest rate setting board and by far the most influential person on it apart from Bullock.

Kennedy’s dual role is unheard of in other developed economies, which removed any perception of direct government influence over monetary authorities long ago.

But this institutional oddity rates barely a mention in Australia.

Kennedy says he acts independently of the government in his RBA role, but at the very least it places him in an awkward position.

The truth is Kennedy is deeply influenced and shaped by power. He is a political animal at the heart of the Canberra bureaucracy. This is chiefly because of the power governments hold in hiring and firing secretaries at the drop of a hat, forcing secretaries into the political realm: not publicly – where they are expected to play the role of a detached technocrat – but covertly.

Effective secretaries take full advantage of this dual existence, exercising immense, largely unacknowledged and virtually unchallenged influence. They operate largely in the shadows. They cultivate and make good use of journalists, they privately lobby crossbenchers on contested legislation and, at critical junctures, act as a conduit between ministers’ offices and departmental officials. In each instance they operate well out of the public eye, at times blurring the line between the bureaucratic and political.

Kennedy himself is close to the Treasurer. Chalmers is wary of many in the Treasury department, but he trusts and depends heavily (some say too heavily) on Kennedy, whom he got to know when he worked as an adviser to prime minister Kevin Rudd. Both men are ideologically aligned.

While Kennedy, unlike Chalmers, is a trained economist, he has an expansive vision of the role that governments can play in the economy, lacking the traditional Treasury aversion to big state interventionism.

Like many of the nation’s most senior public servants, Kennedy is a passionate believer in net zero and other progressive agendas – and sees these as moral, as well as economic and social, imperatives that are beyond dispute.

I have known Kennedy for close to two decades but have never been close to him. It is fair to say our world views are quite different, but I have always acknowledged his energy, diligence and sense of mission.

Kennedy’s relationship with Chalmers raises important questions. When Chalmers publicly attacks the RBA board’s interest rate policy, does this reflect what Kennedy has been telling him as Treasury secretary or is this just freelancing?

Is the board’s current and highly unorthodox strategy – which emphasises protecting post-pandemic employment gains even at the cost of prolonged above-target inflation – one he has supported in this body? If Kennedy’s pivotal position in this power play was acknowledged, these questions would inevitably be asked, making life exceedingly difficult for himself, Chalmers and Bullock.

But his dual role, while in plain sight, is conspicuously ignored or downplayed.

I can understand why Chalmers and Bullock do this, but why do our political and financial commentators play along with this charade?

In the private sector, such an apparent conflict would not be tolerated for a moment. Yet when a senior federal government official is involved, not a sceptical peep is heard. Why?

Part of the explanation is that Kennedy is a public servant, a designation that, in Australia at least, seems to guarantee the holder a free pass from any kind of critical scrutiny.

Here, public servants are often assumed to be politically neutral technocrats, guided only by their subject matter expertise and the objective evidence before them. It’s assumed they act like artificial intelligence automatons that are programmed to tune out the potentially corrupting influence of politics, power and self-interest.

For any Canberra insider, this conception of public servants is laughable, but remarkably the fiction is maintained publicly by ministers, who can hide behind supposedly neutral bureaucratic advice to justify controversial policy calls (as they did during the pandemic); by senior public servants themselves, to allow them to help their political masters in this way; and, remarkably, by many journalists who cover public affairs. For them, it’s far better copy to pretend that Kennedy and other secretaries are at arm’s length from the government, delivering public advice – even dire warnings – to their ministers in their speeches and statements.

In truth, they do not utter a syllable that is not cleared with ministers and their staff beforehand.

Just as in any other cloistered institution, whether the Catholic Church or Goldman Sachs, no career public official can rise to the top without being extraordinarily ambitious in seeking power for themselves. When have you heard the media describe a top bureaucrat as ambitious, let alone ruthless? Perish the thought.

I am not bemoaning the influence of power in Canberra. It’s unavoidable in any system of government. And power can be put to good as well as nefarious uses. But as astute observers have always recognised, power – the proximity to it, the possession of it, the desire for it – can subtly affect and shape us all.

It can skew our judgments. To deny that psychological reality would be the height of naivety. We can never eliminate power from government, only try to limit its potential corrupting influence.

Two strategies have been adopted in this regard. First, to divide and fragment it, so no individual or body can have access to several sources of power – and exploit the conflicts these give rise to. Second, to hold those who wield power to account.

But the secretary’s monetary policy role violates both of these principles.

This one person advises the Treasurer on the legislative framework governing the RBA and performance of that institution but at the same time sits on the RBA’s board. They are both policy adviser and regulator. Bureaucrats aren’t allowed to sit on the boards of other economic regulatory bodies, only the RBA.

A sceptical parliament, opposition and media would be an important check on the secretary’s power, but that is lacking. An egregious example of this was the response to last year’s deeply flawed RBA review.

For students of Canberra power plays, the review’s focus and major recommendations were no surprise. It served the interests of Chalmers (who appointed the review team) and Treasury (which hosted the review secretariat) beautifully, while delivering a hammer blow to the RBA. Sir Humphrey Appleby would’ve applauded it.

The review recommended a new interest rate setting board, potentially allowing Chalmers to stack it with Labor-friendly appointments. As former RBA governor Ian Macfarlane pointed out at the time, it proposed to drastically weaken the RBA’s representation on this body, raising the possibility of the governor being outvoted on interest rate calls.

Did it recommend that the Treasury secretary be removed from the new board? Of course not. This was despite not one but two papers the review commissioned from international experts expressing misgivings about the arrangement. One said the mere “attendance” by a senior government official – let alone being a full member – risked a perception of “undue government influence” over monetary policy decisions. The other said Treasury’s current role “compromises” the RBA and is “counter to international best practice”.

While the review was critical of the RBA (which it portrayed as insular and riddled with groupthink) and the board’s external members (which it derided as lacking in economic expertise), highlighting the board’s errors during and after the pandemic, it made no reference to Kennedy’s pivotal role at this critical time – despite him having been on it since late 2019.

Yet most commentators and the opposition, at least initially, gave these findings an uncritical green light.

The Treasury secretary should no longer sit on the RBA board. It is inconsistent with the perception of central bank independence and a hangover from a past era when governments controlled interest rates. There is no such thing as independence in Canberra, least of all among our highly politically attuned secretaries. To claim there is would be akin to pretending a cricket ball in flight is independent of the Earth’s gravitational force.

Defenders of Treasury’s participation on the board – and oddly there are many – assert that “it has always worked” in the past. A sceptic would reply: “How do they know?” Monetary policy calls are often finely balanced: technically sound arguments can be made for each option under consideration.

Even if a secretary convinces themselves that they’re being guided only by the facts, how do we know political and career considerations play no role in their reasoning?

Kennedy may face his moment of truth in the lead-up to the federal election. Will he be willing to sacrifice the Albanese government and risk his own position (by exposing himself to the prospect of dismissal by an incoming Dutton government) by arguing against the cash rate cut early next year, when one is more likely? Or will he support one?

If the individual votes of RBA board members were reported by name, as they are in Britain, the public would at least know which way they jumped. Until the same arrangement is introduced here in Australia, Kennedy will remain what he is now, the nation’s invisible, and mostly unaccountable, central banker.

David Pearl is a former Treasury assistant secretary.

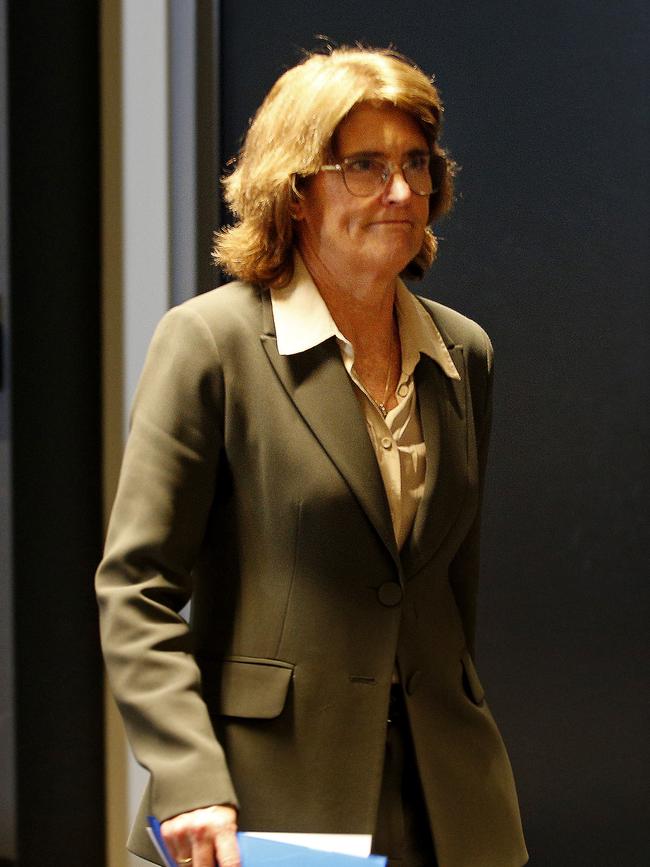

In the lead-up to a federal election that’s likely to be decided by the Reserve Bank’s next interest rate move, Jim Chalmers’ working relationship with RBA governor Michele Bullock is strained, to say the least.