The long march of China’s communist rule

When the 13 apostles of embryonic Chinese communism met for the first time in a Shanghai school room, they scarcely dared hope they’d one day be the world’s most powerful party.

When the 13 apostles of embryonic Chinese communism met for the first time, in a school room in a backstreet of Shanghai’s French Quarter in midsummer, they scarcely dared to hope that one day they would be in a position to seize control of their country as their Soviet big brothers had done four years earlier.

It eventually took them 28 years. Today, 100 years on, theirs is the most powerful party in the world.

Opportunity seemed to knock for revolution in China, after the last Qing emperor had been deposed a decade earlier. But China’s population was then overwhelmingly rural, and it was only when Mao Zedong – just a minor figure at the founding – later began to rethink the Chinese Communist Party’s focus, directing it towards farmers, rather than towards factory workers on whom the Soviet Bolsheviks had built their support base, that it gained real traction.

The party struggled to gain the upper hand against the governing Kuomintang, or KMT (Nationalists), who had also initially won support from the Soviet Union. The watershed came in 1927, as the KMT, now under Chiang Kai-shek, cemented control over eastern and northern China which had fragmented after the six-year-old emperor abdicated. The KMT started to purge members of the CCP, which had formed its own Red Army seeking to seize power.

By 1934-1935 the Red Army appeared on the ropes, forced into a lengthy series of retreats from southern China heading west then north – during which Mao took over the leadership and shrugged off the party’s pontificating Soviet advisers. This episode was transformed into mythical triumph as the Long March.

The Japanese invasion, which had begun in the northeast in 1931 and intensified in 1937, proved the catalyst that ultimately enabled the CCP to take control of China. The KMT government’s troops were eventually exhausted and depleted by their eight years’ constant fighting the Japanese, while the fresher Red Army was replenished with Soviet weaponry.

Mao promulgated the new People’s Republic of China on October 1, 1949. Party officials soon launched purges, of people dubbed as “landlords” – reflecting the core communist attraction to many Chinese people, that they would be given land of their own to farm, taken from those newly labelled as Marxist class enemies.

However, the “peasants” were doomed to disappointment. The land was instead communalised, and ruled by party officials.

Progressive thinkers, writers, artists and professionals, who had backed the CCP against the more conservative and corrupt KMT, were lured into frank critiques of the increasingly dogmatic new regime by Mao’s deceptive “Let 100 Flowers Bloom, Let 100 Schools of Thought Contend” slogan. Up to two million such “Rightists” were killed during the 1950s.

Mao’s next campaign, his Great Leap Forward from a family-based agrarian society towards an efficient communist industrial one, proved the greatest disaster heaped on a single nation in human history, leaving up to 55 million dead.

After this catastrophe the party elders wrenched back the controls from the increasingly out-of-control Mao. But he deployed his hero cult to unleash the teenage Red Guards to “bombard the (party) headquarters”, declaring as the decade-long Cultural Revolution’s theme: “Everything under heaven is in utter chaos; the situation is excellent”.

Deng Xiaoping rescued the party, after Mao’s death in 1976, by releasing first farmers then small-scale businesspeople to run their own affairs, while ushering in foreign technology, management and, in some areas, capital. This helped unblock the barriers to prosperity the party had built 30 years earlier, and gave it a new source of legitimacy.

In 1989, young Chinese demonstrated for greater political and personal freedoms, and for party accountability as rising wealth had fed corruption. They were eventually quashed mercilessly by the People’s Liberation Army, which is the party’s army, not China’s.

To prevent recurrence and cement party loyalty, the middle class was provided further opportunities to prosper, and the universities were funded generously. And the danwei culture – with everyone living where they worked – was dismantled.

Deng’s party meritocracy was unravelled as the Reform Era he launched was replaced by Xi Jinping’s New Era that validates instead the authority of “red genes”.

Deng was succeeded as paramount leader by Jiang Zemin, then Hu Jintao, who both adopted a committee-focused governance style that balanced influential factions, dispersing decision-making. That seemed appropriate, since uniquely for such a vast country, China lacks a federal structure.

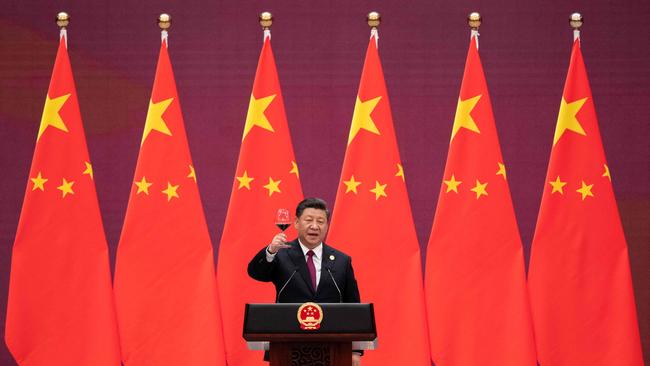

Xi has instead recentralised and personalised power. His New Era venerates the party’s founding myths including those enshrining Mao, whose body remains on view to visitors to Tiananmen Square, across which his massive portrait stares out imperiously as the CCP’s second century starts.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout