The Liberal Party descended into chaos with the departure of John Gorton

Fifty years ago the sturdy edifice of the Liberal Party shattered in events that began on, and played out across, the front pages of this newspaper over a single week

On retiring as prime minister, Robert Menzies left his country in good shape and his party in safe, stable hands. Or so he thought.

Menzies’ successor Harold Holt had been in parliament decades and was elected unopposed to replace him. No Australian can forget that day: the Beaumont children were snatched from Adelaide’s Glenelg beach at lunchtime and remain missing. At the federal election that followed, the Coalition gained 10 seats and Labor lost nine. Holt entered what we now know as the Old Parliament House on February 21, 1967, with an understandable swagger; his coalition held 82 seats, twice the number of the crushed members who sat opposite.

The seeds of one’s destruction can often be sown at such a time. A smug, serially unfaithful Holt carried on as before, his overconfidence eventually taking its toll on December 17, 1967.

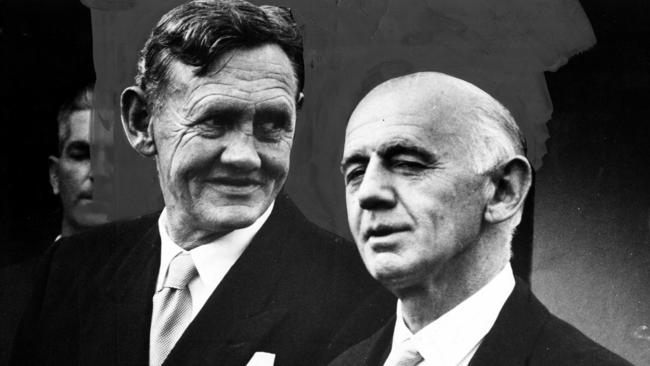

Menzies’ succession plans were upended when Holt was lost at Portsea. And senior party ranks were thinner than he imagined. Shocked Liberals, in an unprecedented gamble, reached into the Senate to replace Holt with John Gorton — as unconventional a choice as he was an unorthodox captain.

The freewheeling disorder of his prime ministership briefly won him many friends. “Gorton was a rough ride,” said Tony Staley in Melbourne this week, then a parliamentary colleague and later party president. “(But) Gorton was a character. He was genuine.”

And if the country was at first mesmerised by the colourful, plain-talking World War II flying hero — a school classmate had been Errol Flynn — this quickly turned to disappointment.

Gorton was a centrist — seen then as a Labor trait — and he put offside some influential premiers, notably NSW’s Bob Askin and, more damagingly, Victoria’s dominant Henry Bolte. He inherited Holt’s position of staying in Vietnam and, despite private doubts, stuck with it. On May 8, 1970, record numbers of young Australians — more than 200,000 — marched in the first national moratorium. It had been less than four years since Holt had uttered the infamously thoughtless words “All the way with LBJ”.

It may as well have been a lifetime. And Gorton’s first year as leader would be Australia’s worst for casualties in Vietnam. Stories of Gorton’s drinking were common and his reputation was dented when, perhaps over-refreshed, he took 19-year-old reporter Geraldine Willesee — her father was the senator Don, her brother newsman Michael — to the US embassy late at night after a function to demand an update on US plans to stop bombing North Vietnam. Once a supporter, then defence minister Malcolm Fraser soon lost faith.

Then came a front-page story by Alan Ramsey in The Australian on March 4, 1971. He reported that chief of the army general staff, Sir Thomas Daly, believed Fraser, in an effort to compromise the army minister, was undermining our Vietnam forces. Under Fraser, who was in cabinet, were ministers for air, navy and army. Andrew Peacock was the army minister.

A lifelong feud was born. Daly’s complaint had reportedly been revealed to Ramsey by Peacock’s wife Susan, and Ramsey had taken to Gorton the explosive claims the night before publication.

The story played in The Australian for several days. In 1964, British prime minister Harold Wilson had said “a week is a long time in politics”. Gorton’s enemies were about to prove it.

A day after Ramsey’s incendiary news story, we carried the headline: “PM says Daly story untrue”. But there was another Ramsey story: “Gorton knew of report”.

Gorton had lost support, but his fate was in the balance. Accused of disloyalty by Daly, Fraser went to see Gorton, cancelling a planned trip to Vietnam. Fraser was Gorton’s greatest threat. If our military had lost faith in the minister, surely that minister was on thin ice.

Monday’s The Australian reported Daily Telegraph Canberra correspondent Alan Reid had said cabinet members were more afraid of Gorton than they had ever been of Menzies. He said Gorton was seeking to “assassinate” Fraser.

Fraser resigned, stating: “I regard your conduct as prime minister as one which indicates significant disloyalty to a senior minister. Such a situation is not tolerable.”

Explaining in parliament the circumstances of his encounter with Ramsey, Gorton sought to hide his motive for allowing the story to be published. From the gallery above were bellowed the words, “You liar!”

“I couldn’t believe I’d said it,” Ramsey later recalled.

Ramsey apologised for his outburst in the next day’s newspaper, but there was no relief for Gorton. That same page carried the headline: “Gorton Decision Today”.

It was Wednesday, March 10. Overnight had been frantic, with support for Gorton evaporating. The party would nail its leader, but who would succeed him? William McMahon was qualified, but far from popular.

“Malcolm Fraser lost me over the way he handled those days,” Staley said this week. “Then the way he urged me to support McMahon. I said no way. I was dead against it … I couldn’t face voting for that crank McMahon.”

What happened in the party room was unprecedented. The motion of confidence in Gorton’s leadership was tied because one vote was informal. Gorton then sacked himself with a vote from the chair, a move outside the party’s rules.

Another vote sought to find a new prime minister, with McMahon defeating Billy Snedden. Gorton, always with a surprise up his sleeve, contested the deputy leadership and won, defeating two candidates, one of them Fraser. Staley thought it all a disaster.

“He (McMahon) made his reputation leaking to the Packers (then publishers of The Bulletin and Daily Telegraph). He was straight out of cabinet and straight on the phone to the Packers,” said Staley. He says Menzies was flattened, expressing “astonishment that we had made him leader”.

“McMahon was the least genuine normal human being you’d ever meet,” said Staley.

Staley told colleagues that the party would be a laughing stock within months, but “it took about six weeks”.

Staley recalled McMahon’s chief of staff bringing a delegation to see the recently installed prime minister to tell him of the various things the new office would require. The senior insiders sat around their new boss. “Righto, then,” McMahon said with authority, reaching for the phone. He barked some instructions: “I’ve got important people with me” who wanted this and that “and I want you to fix them right away.”

Whitlam had famously mocked McMahon, likening him to a legendary scheming Roman — “Tiberius with a telephone”.

“The only problem was there was nobody at the other end of the line,” Staley recalled. “Isn’t that amazing?”

The Liberals were doomed from March 1971. The next Liberal leader, Snedden, would be the first not to become prime minister.

Was McMahon Australia’s worst prime minister?

Staley thinks so: “If not, it’s a close run thing. Arguably he is the worst.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout