The lawyer who saw America’s ‘useful enemies’ as plain monsters

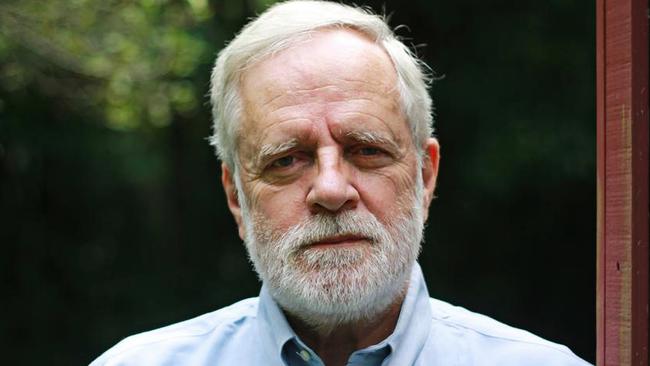

Low-key lawyer Allan Ryan never gave up hunting down those who had helped Hitler’s Holocaust.

OBITUARY

Allan Andrew Ryan

Born July 3, 1945, Cambridge, Massachusetts; died Norwell, Massachusetts, January 26, aged 77.

-

Elizabeth Holtzman was the youngest member of the US congress in 1973 when she was told by a lowly whistleblower working in immigration that her government not only knew Nazi collaborators were living in the US but had a long list of the unaccountably protected men and women – “useful enemies”, they were called.

She was appalled. Indeed, she could barely believe it. Soon after, Holtzman attended a budget session of the Immigration and Naturalisation Services department to ask its commissioner if such a list existed. He said it did. She asked to see it and was given 59 dossiers on brutal concentration camp overseers, cruel guards, who had tortured and killed women and children, and even gas chamber operators.

There were thousands of such barbarians calling America home. They may not have been the architects of the Final Solution but they were its loyal foot soldiers without whom there could have been no Holocaust.

Holtzman’s Office of Special Litigation Unit swung into action as the world marked the 40th anniversary of Germany’s invasion of Poland in 1939.

Justice Department lawyer Allan Ryan was put in charge and by 1979 the era of organised Nazi hunting was under way. And it would change lives. The first it changed was Soviet-born Treblinka camp worker Fyodor Federenko. He was an enthusiastic killer of Jews, whom he liked to humiliate in their final moments – like making them crawl naked around the camp. He had tricked his way into the US under the Displaced Persons Act, become a US citizen in 1970, spent decades in a Philadelphia metal factory and retired to Florida.

Federenko’s name was on Holtzman’s list. He had been recognised by a few survivors over the decades, not least of which when cheekily he took a holiday to Crimea.

He was challenged about his citizenship, but a District Court judge doubted the memories of those who gave evidence. Ryan picked up the case and appealed, pointing out the lies Federenko had told to enter the US. Ryan won and Federenko was returned to Crimea where he was put on trial, during which it was revealed 800,000 had been killed while he worked at Treblinka. Aged 79, he was convicted of war crimes, sentenced to death and dealt with by firing squad on July 28, 1987.

Ryan also looked into the case of The Butcher of Lyon, Klaus Barbie. He reported back that Barbie’s escape to Bolivia had been abetted by the US government. Ryan found that, in the clamour to undermine communism, America had assisted such men, including Barbie, to find sanctuary in South America. Barbie hated Jews and personally tortured many of them before their deaths.

On the strength of Ryan’s investigations, the unrepentant Barbie was extradited to France – he had twice been sentenced to death in absentia – and died there, appropriately in Lyon where he had been the Gestapo chief. After seeing Ryan’s evidence, the Reagan administration apologised to France for America’s actions decades before.

Ryan was also key to the extradition to Germany of John Demjanjuk – a retired Cleveland Ford factory worker – who, while not being the notorious cruel camp guard Ivan the Terrible as suspected, was extradited first to Israel and then Germany, where he was found guilty of being an accessory to the murder of 28,000 Jews at Poland’s Sobibor extermination camp.

Ryan left government service soon after and lectured at Harvard and advised veterans’ legal services, but he became engaged in the interaction between the law and the military, a complex area where justice is sometimes compromised as understandably angry victors seek retribution.

In 2012 he published an acclaimed book, Yamashita’s Ghost, about the General Douglas MacArthur-driven trial of Japanese General Tomoyuki Yamashita following the liberation of The Philippines and victory in the Pacific. Troops under Yamashita’s nominal control had run riot raping, torturing and beheading locals, often children, as the war wound down and Japan’s defeat was inevitable. It is unlikely Yamashita knew of many, or any, of these crimes. He had not ordered them. But MacArthur, inventing law on the run, said Yamashita should have had control of those men, and perhaps that is right.

Predictably, MacArthur won the verdict he sought and it is now referred to as the Yamashita standard. Yamashita was hanged on February 23, 1946, but it is still vigorously debated if justice was done. As he ascended that scaffold, Yamashita’s last words were: “I don’t blame my executioners. I will pray God bless them.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout