The dream of Queensland’s unlimited potential is deep-rooted: Can the Crisafulli government meet the challenge

Labor scrapped its traditional strength, development, for debt. Can David Crisafulli turn Queensland’s fortunes around?

Like bankruptcy, the wipe-out happened slowly, then all at once.

The Queensland election, held a month ago, did not merely cost Labor government; it also signalled the ALP’s collapse in the state’s sprawling centre, north and west.

With Labor annihilated in seats that had remained safely in ALP hands for most or all of the past 100 years – including heartland provincial centres such as Rockhampton and Mackay – everything suggested Queensland politics might finally be in the process of being redefined.

Not that Queensland changes sides easily. On the contrary, the largest and most geographically, demographically and regionally multi-pronged state in Australia has never lent itself to rapid shifts in power formations.

Labor held government from 1915 to 1957, barring three years, then the Nationals and Liberals ruled uninterrupted for 30 years to 1989. The following quarter century was solidly Labor’s, excepting two brief National and Liberal National Party interregnums.

Nor is the infrequency of change the only respect in which Queensland has tended to differ from its counterparts. Together, history and geography have forged a unique political identity.

Unlike in the southern states, self-government, when it came in 1859, occurred not only simultaneously with the arrival of mass suffrage democracy but while the colony was still in the throes of frontier conflict and the rapid expansion of settlement.

The rugged frontier style of life became, as it did for some states in the US – one thinks of Texas – not only deeply embedded but definitional. So did the urgent, almost existential drive to develop the state to its full potential.

At the same time the sheer thrust of development, spiralling out from Brisbane in the state’s extreme south to the remote north and west, marked the colony with a fundamental reality no other colony (and later no other state) had to contend with: the polity could not be governed and controlled from its largest metropolitan centre. Even today, when Brisbane’s size and proportionate influence is greater than ever, more than half the state’s population live outside the capital city.

Whereas political groupings and then modern political parties in other states could count on commanding the hinterland by consolidating power in the capital, that was never the case in Queensland. Elsewhere, transport and communications converged on the capital; Brisbane had to deal with an enormous seaboard of many hundreds of kilometres, punctuated by provincial towns and outports whose extensive road and railway connections serviced their own hinterlands of goldmines, sugar cane plantations and vast pastoral stations.

In turn, this physical immensity rendered Queensland into what historian Russel Ward typified as a “big man’s country”. What Ward meant was not so much the individual pastoral kings and other would-be magnates but the required scale of operations.

Unlike the homesteader farms in the US, or the expansion, aided by selection acts, of a wheat-growing yeomanry down south, in Queensland large stations employed teams of men to perform its work. The crew culture of Queensland’s labouring men, who weren’t solely tied to one workplace, was the seedbed for Ward’s “bush legend” – a legend that framed an image combining knockabout individualism with an ethos of mateship.

But that ethos also lent itself to violence. Setting a pattern that recurred in other spheres of Queensland life, the Great Strikes of the 1890s were among the Australian colonies’ most violent. Armed confrontations between shearers and pastoralists led to Samuel Griffith (premier 1883-88 and 1890-93) declaring martial law as the colonial dream of “the workingman’s paradise” fell to pieces.

In the aftermath of the defeat of previously powerful unions, the labour movement turned to other solutions, namely the establishment of a political party to represent their interests in parliament, and a system of state intervention to recognise unions as well as employers and resolve industrial disputes. The ALP and arbitration were born.

In contrast to the dominantly urban Labor Party organisations springing up in southern capitals, Queensland’s Labor Party immediately established strongholds in the bush and coastal regions far removed from Brisbane. Rural Queensland workers – miners, canecutters, bush workers, small farmers and provincial industrial workers – provided the mass of support. This was evident as early as 1893, when most of the 16 seats the new ALP won in Queensland’s general election were in the colony’s distant north and west.

In 1899 the world’s first Labor premier, Andrew Dawson, occupied the electorate of Charters Towers, 1300km from the state capital. The five ALP premiers of Queensland after 1915 all represented far-flung country seats: Thomas Ryan (the Barcoo electorate in southwest Queensland, premier 1915-19); Edward Theodore (Chillagoe on the Atherton Tablelands, 1919-25); William Gillies (Eacham, also on the Atherton Tablelands inland from Cairns, 1925); William McCormack (Cairns, 1925-29) and William Forgan Smith (Mackay, 1932-42).

The ALP’s great success outside of Brisbane was helped by the fact Queensland became even more regionally focused after Federation. The loss of Queensland tariff walls led to the collapse or decline of manufacturing and other urban industries as cheaper manufactured goods flooded in from southern states.

With manufacturing shrinking, Queensland gravitated more and more towards the production and transport of sugar, wool and meat, all of which pushed the state’s centre of gravity far from the capital city.

In turn, rural dominance shaped the revamped union movement that emerged out of the industrial tumult of the 1890s. The Australian Workers Union, which covered a grab-bag of industries and occupations, absorbed the bulk of the rural workingmen who had been embroiled in the Great Strikes.

Having seen up close the devastating consequences for union power of naked class struggle, the AWU was an early and ardent convert to the cause of arbitration.

In Queensland, though, the AWU distinguished itself in significant ways that structured the state’s subsequent power relations and political culture. Unlike the other, smaller branches of the organisation in other states, Queensland’s AWU deployed a highly centralised structure that allowed it to concentrate decision-making power in a tiny handful of officeholders.

“The more power in the hands of a central body, the greater the general success,” Theodore said in 1913.

The functional Bolshevisation of the largest union in the state paid off, as it co-ordinated its enormous membership to effectively control most of the ALP’s northern branches, then take over the ALP’s parliamentary wing. Soon, the AWU’s dominance of caucus and cabinets was hardwired into the Queensland ALP machine.

That machine had one dominating instinct: state development. The dream of Queensland’s unlimited potential has roots as deep as the bush legend.

“Queenslanders have ever been receptive to talk of development,” one historian notes, as far back as Thomas McIlwraith (premier 1879-83, 1888 and 1893). McIlwraith created the original mould of classic Queenslander: bigger than life, a burly, visionary larrikin who took his expansive and buccaneering entrepreneurialism into politics. His promise was not orderly, competent or even particularly honest government. It was uninterrupted material progress.

The Labor decades of dominance became possible only after a string of ALP premiers devised their own version of supercharged development for the regions. All their efforts focused on building a “small man’s paradise”, as against the big businessmen and investors McIlwraith had favoured.

Railways were pushed still farther out to create closer settlement, encourage agriculture, help miners, small-scale sugar and cotton-growers, and create jobs for countless construction workers and railway navvies. At the same time, Labor eroded the checks and balances on its form of radical democracy by abolishing the state’s upper house in 1922 – and then, in 1949, entrenched rural dominance through an electoral redistribution bill that gave country voters a disproportionate influence on the composition of the state’s legislative assembly.

But as so often happens, the gerrymander that was intended to perpetuate Labor dominance helped bring it to an end. The scheme was introduced by Edward (Ned) Hanlon (premier 1946-52), the implacably anti-communist son of an Irish agricultural labourer. Denouncing the communist “interlopers from the south” who would have “Queenslanders bend their knees before the first mimicking Molotov who enters the country”, his government passed state of emergency legislation that helped break the 1948 railway strike – and that set the template used decades later by Joh Bjelke-Petersen to outlaw demonstrations and break strike action.

However, the virulent anti-communism that pervaded the heavily Catholic-oriented state Labor Party ensured that the maelstrom leading up to and past the Split was more devastating in Queensland than anywhere else.

The Catholic right was not a faction or splinter group; it was the bulk of the Labor government. The party’s civil war destroyed its own government and its hopes of governing. With non-metropolitan areas remaining deeply conservative and as staunchly anti-communist as the party’s traditional leadership, the gerrymander condemned the parliamentary Labor Party to permanent opposition.

Yet even without the fratricidal politics of the Split era, Labor’s domination of the remote rural, regional and provincial centres was slipping as country Queensland underwent sweeping economic and social change.

Union membership in Queensland was proportionately greater than anywhere else in Australia in the decades after the Ryan government’s Industrial Arbitration Act in 1916 first enabled judges of the court to preference unionists over non-union workers. But with the mechanisation of rural industries thinning out the regional unionised labour force, union density in Queensland dropped 25 per cent in the decade to 1973.

A new country Queensland was emerging. The bulk shipping of base metals to an increasingly hungry global market encouraged the rapid development of new mines, in a trend magnified still further by the 1970s commodity price spikes.

Bauxite, alumina, coal, oil, gas and uranium were all part of a new mix of boomtime regional development. Its private sector bias was in striking contrast to the state investment approach of the Labor governments.

This vital formula helped Bjelke-Peterson, the peanut farmer from Kingaroy, define and implement a resource-oriented version of state development that converted the Nationals into an election-winning machine.

Bjelke-Petersen used the new royalty streams to cement Queensland’s reputation as the low-tax state. Increased provision of services to regions and remote provinces was funded not by expanding the rate of taxation, as Labor had pioneered when it introduced a land tax in the 1920s to go with increased income and company taxes, but by formidably expanding the revenue base.

The coal, bauxite and uranium royalty streams complemented the development of new hotels, casinos and tourism. The regions were kept happy with more jobs, often better paid than the ones that had been lost because of mechanisation.

In the eyes of most, working in a newly airconditioned hotel or in highly paid mining work was a damn sight more salubrious than cutting cane in difficult, hard-tropic, frequently rat-infested, conditions.

Crushed by the Nationals’ steamroller, Labor ceased to regard itself as a serious alternative government, its safe parliamentary seats treated as early retirement options for trade union powerbrokers. What historian Ross Fitzgerald describes as the “Tammany Hall-style trade union oligarchy” eroded any relevance the party might have had to the public conversation.

The Trades Hall Group, also known as the Old Guard, continued the Queensland labour movement tradition of tightly concentrating power within an extremely small group, in this case a seven-member inner executive with responsibility for all major decisions governing the party. They were responsible for a never-ending series of state and federal election disasters through the 1960s and ’70s.

The 1977 federal Senate showed Labor support collapsing to a then record low of 34.5 per cent in the heyday of almost total Coalition-Labor dominance of voter allegiances. Queenslander Bill Hayden, now leading the federal ALP, led a federal intervention to rebuild the party in 1980, working with the Queensland ALP reform group, a younger generation of Labor intellectuals, academics, unionists and activists, who had been repeatedly shut out and silenced by party elders.

Oddly, the new generation of university grads resembled most of all McIlwraith’s 19th-century arch-enemy, Griffith. Griffith had been the Brisbane-based university liberal progressive who had run anti-big men coalitions against McIlwraith’s Nationalists before vaulting to the Federal Conventions and, after Federation, the newly established High Court of Australia.

Griffith’s name looms large in national memory because of his role as one of the key architects of the Australian Constitution, while McIlwraith is little more than a footnote. The reality of Queensland’s political tradition reverses this. Griffith’s liberalism had vanished in the early 1900s without leaving any real trace. But there are elements of resemblance between Griffith and the metropolitan Brisbane reformers and legalists who rose to prominence in the Wayne Goss (1989-96), Peter Beattie (1998-2007) and Anna Bligh (2007-12) years of the 1990s and 2000s.

By this time the pro-regional electoral bias had been reformed out of existence while greater Brisbane’s share of the state’s population, from Coolangatta to Noosa, had grown dramatically.

This increasing density and scope finally gave Brisbane – and the urban professional class – some of the political heft other state capitals have always assumed as metropolitan birthright.

Reflecting that shift, the second-wave ALP premiers, from Goss to Steven Miles, all represented electorates within or on the outskirts of Brisbane – as had Griffiths. Nonetheless, regional cities such as Townsville, Rockhampton, Cairns and Mackay, and their regional hinterlands, remained vital to the party’s parliamentary majority. For that majority to survive, development had to retain its pride of place in the pantheon of the state ALP’s values.

But by the dawn of the 21st century the Greens’ environmentalism had converted development, which had always been the royal road to Queensland power, into a fraught term in metropolitan circles, more apt to be a term of abuse than a boast. Facing, for the first time, an effective challenge from the left, the ALP turned against development in a bid to defend embattled inner-city seats, abandoning the vision that had propelled it from its earliest days.

That process wasn’t without its twists and turns, as the limb-wrenching contortions that jumbled state Labor’s response to the Adani coalmine project showed. To make things worse, social media’s ubiquity, combined with 24/7 media focus on political statements, meant one could no longer tell one thing to Mackay and something completely different to Toowong, confidant that neither group would hear the promises being blasted out to the other.

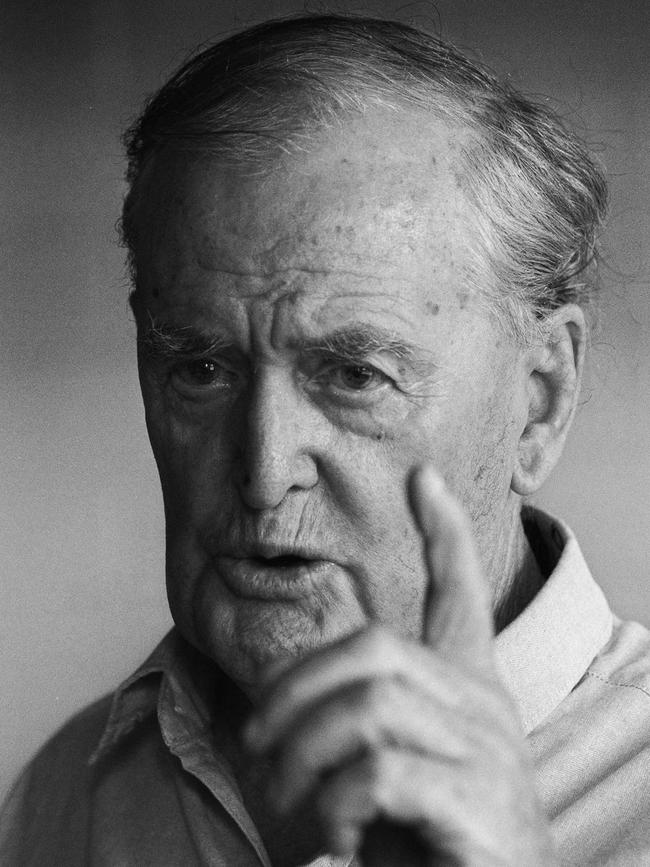

Trapped in a conundrum, the governments of Annastacia Palaszczuk and Miles tried to use money to paper over the cracks, on a scale that became ever more feverish as the end approached. The change, compared with the past, could scarcely have been more extreme. Queensland had an extraordinarily long history of fiscal prudence, quietly enforced by Sir Leo Hielscher, the eminence grise of the state’s finances from 1964 to 2010. Spending restraint, combined with an emphasis on expanding royalty streams, was mirrored in a low tax burden: by the close of the Bjelke-Petersen years, the effective tax burden in Queensland was fully one-third lower than the all-states average and only half that in NSW.

The commitment to fiscal restraint was broadly maintained by the governments of Goss and Rob Borbidge (1996-98), but the election of the Beattie government in 1998 marked a fiscal turning point. Beattie and then Bligh all but buried the fiscal rules that had been formalised by their predecessors.

Thus, beginning in 2005-06, effective tax rates exploded, with Queensland entirely losing its status as the low tax state. However, those increases didn’t suffice to prevent a lengthy run of budget deficits, causing the state to lose its cherished AAA rating in early 2009. Elected in 2012, the government of Campbell Newman sought to redress the balance, handing down three budgets that stopped nominal expenditure growth and achieved small operating surpluses, despite the mining boom coming to a screeching halt in 2012.

Good policy did not prove to be good politics. Newman was thrown out after just three years with the Palaszczuk government landslide in 2015, and soon enough all bets were off. The burgeoning royalties from liquefied natural gas – and the one-off fiscal surplus in 2022-23 caused by the Ukraine war-driven spike in global resource prices – were squandered in the blink of an eye.

Then, in a desperate attempt to buy votes, came the Miles government’s spendathon that, among many other things, unleashed torrents of largesse on public servants, whose wages grew more rapidly than in any other state.

Miles’s abject failure is a stark lesson to Labor nationally. But that does nothing to improve the legacy David Crisafulli has inherited. Since the beginning of this century, state debt per capita has increased at twice the rate of growth of per capita incomes. Meanwhile, productivity growth has been half that in NSW, in a trend that, if allowed to persist, will constrain the state’s overall expansion and hence its ability to manage its burgeoning debt burden. But were expenditure to remain on its current trajectory, spending in 2027-28 would be almost twice its level in 2015-16 – causing the state’s gross borrowings to increase across the same period by $100bn.

The Crisafulli government therefore faces a momentous challenge, all the more so as it will, like the Newman government before it, be subjected to a thousand scare campaigns. Compounding the difficulties, the Albanese government, with its fantasies of converting central Queensland into a renewable energy hub, is viscerally hostile to the fossil fuel projects that remain at the heart of the state’s economic prospects and that underpin the prosperity of large parts of country Queensland.

Nor is it much more friendly to primary industry, which it seems to view as a blot on an environment that ought to be left pristine or used as virgin fields on which to build endless solar arrays and massive wind farms. It is hardly likely to go out of its way to help a resource-embracing, development-oriented LNP government.

A cauldron of contradictions, complexities and, most of all, towering aspirations, Queensland is not just a state but a state of mind.

This much though is certain: steering the state into the future will be no easier than it was in the past. But properly managed, its potential remains as vast as it was when the coming of self-government birthed the great dream of development.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout