Labor of love in Queensland state politics

Thirty years after Wayne Goss swept in, his legacy thrives in Queensland.

It was a sad day when Wayne Goss’s loved ones, colleagues, friends and many admirers gathered to farewell the former Queensland premier at the gleaming Gallery of Modern Art in South Brisbane, one of his finest legacies.

But if you looked carefully there was also something to stir Labor hearts: perspiring gently in the sticky heat was an ex-PM in Kevin Rudd, former federal treasurer and deputy prime minister Wayne Swan, two former ALP premiers and a future one, captains of industry, titans of academe, political shakers and backroom movers from George Street and Canberra — the who’s who of the new Queensland that began with Goss.

His election as premier on December 2, 1989, marked an important punctuation point in Australian political history. Under his leadership, and with no small measure of assistance from corruption commissioner Tony Fitzgerald QC, Labor had ended the unbroken 32-year span of government that had started with then Country Party leader Frank Nicklin in 1957 and reached its zenith during the record 19-year premiership of Joh Bjelke-Petersen, all blown away by the vicissitudes of the Moonlight State.

What Goss could not have known before his death in November 2014 was that Labor’s dominance at the state level in Queensland would go on to rival that of Joh and his fellow travellers. With the exception of two brief but eventful bursts of National Party-led or Liberal National Party government, Labor has held power in Queensland for 25 of the past 30 years, an unequalled record. How the federal ALP must envy it.

Two questions arise as the Queensland ALP celebrates the 30th anniversary of the Goss ascension. First, how has such a long stint of Labor incumbency changed the governance of the nation’s third most populous state, its key public institutions and finances?

The second question goes to the heart of federal Labor’s challenge to reset after the crushing disappointment of the election in May. Why the yawning disconnect between its fortunes statewise and federally in Queensland? The best the ALP did was under Rudd in Kevin 07’s winning outing, taking 15 of 29 federal seats. Its current share of six from 30 seats is much closer to the long-term average.

Reflecting on this, Rudd draws on first-hand experience as Goss’s lieutenant for most of the six years that the reformist state government lasted and from the bitter, near career-ending failure of his first attempt to enter federal parliament in 1996.

He tells Inquirer: “When I heard all of those smart-arses on election night (this year) calling for Qexit because everyone up here was so, in their view, retrograde in their political decisions, I mean, that is just the height of arrogance, not understanding there are large swaths of Australia that are different, and need to be dealt with differently in substance and in communication.

“We must have, therefore, a generic message from the Labor Party about fairness and the future; we must communicate that message differently in different political communities, those different to inner Melbourne and western Sydney. So if you are not from up here and you want to win — because you can’t start 30-down out of a 150-seat parliament — then a leader not from Queensland has … not just to comprehend on paper but to imbibe the sets of differences.”

As detailed in the news pages, Rudd’s recipe for success for federal Labor in his home state involves a tighter connection with local voters than achieved by Bill Shorten or Julia Gillard as prime minister; respect for the state’s thriving Pentecostal churches, a constituency Labor alienated ahead of May 18 by ridiculing Scott Morrison’s faith; and renewed focus on small business, “this large slab of Australia” that needs to come with the ALP for it to return to government in Canberra.

As he earthily explains: “Queenslanders spot a fraud at 50 paces, Queenslanders don’t like shit being poured on religious people — it doesn’t mean they are religious themselves, but they just don’t like that — and, as I said, Queenslanders have pulled themselves up through a small-business culture. It’s simply having the … software to understand those realities, to have policies which deal with each of those realities and language which addresses those realities comfortably.”

Rudd says Labor’s record at the state level belies any notion that Queensland is conservative-voting at heart — though for a quarter of a century it turned out decisively for John Howard (with the crunching exception of 2007), then successively for Tony Abbott, Malcolm Turnbull and Morrison. No other state comes close to matching Fortress Queensland under the state ALP.

Victoria is contemporary Labor’s happiest hunting ground, but the past three decades split 15.8 years of power to the state ALP, against 13.2 for the Liberal-Nationals, currently in opposition there; in NSW, where Gladys Berejiklian governs for the Coalition, the ratio again favours Labor by 16.8 years to 13.3 years for the conservatives.

To drive home the point, it’s worth remembering that those wilderness years for Labor in Queensland between 1957, when the state ALP branch imploded, and Goss’s election in 1989 were preceded by another long period of one-party domination of the state, this time at the hands of Labor, dating back to TJ Ryan’s premiership from 1915. So in this respect they really are different north of the Tweed: once a party gets in, it tends to stay in.

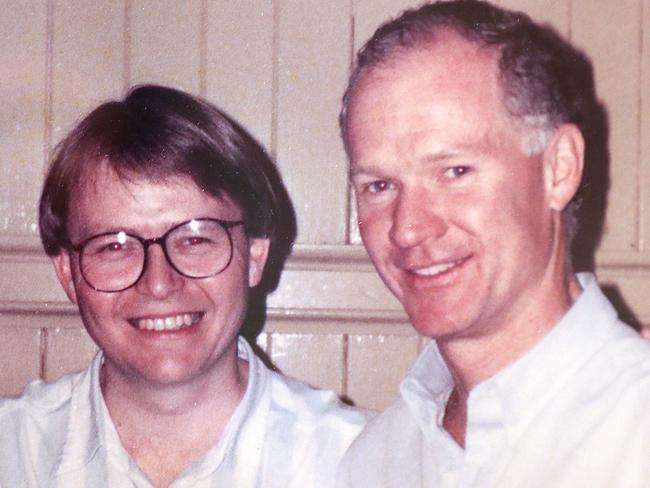

UNTIL he saw an advertisement in The Courier-Mail for the position of chief of staff to Goss, then leader of the state opposition, Rudd was on a fast-track career in the diplomatic service, a world away from the rough and tumble of politics in Queensland. The year was 1988 and Joh had at last been rolled — not by the voters but by his own party, the Nationals, his reputation laid waste by the corruption exposed at the Fitzgerald inquiry. When Rudd applied for the job and was interviewed by a surprised Goss in Canberra — why would you want this, Kevin? — it was two hours before either of them looked at his watch.

Rudd says he was explicit about his reasons for wanting to work for Goss. He was a Queenslander, the place was in his blood, and he was interested in bringing about lasting political change there. At the same time, he had reached a fork in the road, personally. Being a public servant was a good thing, it was a good career, but he wanted to do more than “observe and describe events” in diplomatic cables.

When he finally made it to Canberra in 1998 on his second go at the southside Brisbane seat of Griffith, he joined his then friend, Swan, in federal parliament.

An academic and well-credentialled former Labor staff member who had made his name as the state campaign director in 1989, Swan became treasurer under Rudd, but then became his nemesis in the 2010 leadership rupture that delivered the prime ministership to Gillard. He was Gillard’s deputy prime minister and treasurer but served as a backbencher when Rudd returned as prime minister in 2013 in time to save some of the furniture for Labor — but not the election that brought Abbott to power. Swan was also ALP national president before retiring from parliament at the election in May.

This shows how the tendrils from those early Goss years snaked through successive Labor governments, state and federal, shaping events for a generation to come. Swan’s former chief of staff, Jim Chalmers, has now stepped into his shoes as opposition Treasury spokesman and will be a prime contender to lead down the track. At the Queensland level, a direct line can be drawn from Goss to Annastacia Palaszczuk, who cites him as an inspiration, though they governed in distinct ways.

Goss’s successor as Labor leader, Peter Beattie, entered state parliament at the 1989 election and led the party back to government in 1998, two years after a by-election in Townsville doomed Goss.

Rob Borbidge’s Nationals-led Coalition government did useful things, including rebuilding the M1 highway connection between Brisbane and the Gold Coast, but had no time to consolidate.

Like Goss, Beattie initially ran a tight fiscal policy, delivering big budget surpluses. But by his fourth election victory, in 2006, the purse strings were loosening.

“The real test is what has survived the test of the years,” Beattie says. “For the Goss years it was the accountability mechanisms of the CJC (Criminal Justice Commission) and its successors, and the EARC (Electoral and Administrative Review Commission) reforms to electoral boundaries … for my governments it was education and innovation.”

By the time Beattie stood aside in 2007 for his deputy, Anna Bligh, who had worked for Rudd in the Goss government’s groundbreaking women’s policy unit, the state budget was in deficit. It went deeper into the red as the bills came due for the billions spent on hospitals, power infrastructure and a water grid for Brisbane and the southeast. A woman of the left, Bligh had the dubious distinction of presiding over the downgrading of Queensland’s AAA credit rating during the global financial crisis of 2008-09. The government sold ports, motorways, plantation forests and Queensland Rail’s profitable coal-hauling business, creating a breach with key unions.

When Brisbane’s popular LNP mayor Campbell Newman switched to state politics ahead of the 2012 election, Bligh’s fate was sealed. He won the biggest victory in Australian political history, securing 78 of 89 seats, surpassing Beattie’s haul of 66 seats in 2001. None of Bligh’s presumptive successors survived; Labor was reduced to a rump of seven MPs led by Palaszczuk, who had been a competent but not especially eye-catching mid-ranked minister. Her father, Henry, was an MP under Goss and served in Beattie’s cabinets before paving the way for his daughter to take over his seat of Inala, covering the outer southside area where Goss grew up.

The man who delivered the eulogy at Goss’s funeral, Glyn Davis, worked on the public sector management commission that purged the leadership of the public service in Goss’s opening term as premier. Davis, a career academic, became chief of staff to Beattie before returning to the university sector.

Like Borbidge, Newman made a start on unpicking the tangled web of Labor patronage. This extended beyond the executive service in the government’s towering new HQ at 1 William Street, to the boards of state agencies and corporatised businesses that had been stacked with ALP appointees over the years — for better or worse. But Newman, too, ran out of time.

Since Palaszczuk’s stunning win in 2015, mobilising the backlash against the short-lived LNP government’s unpopular job and service cuts, the politicisation of the judiciary has become a hot-button issue, brought to a head by a rebellion of judges and senior legal figures against Newman’s installation of former Family Court judge Tim Carmody as chief justice. Even before he was promoted from chief magistrate to the top judicial post in 2014, Carmody’s qualifications and experience for the position were publicly questioned by former solicitor-general Walter Sofronoff QC, now president of the Queensland Court of Appeal.

In a rare public intervention, Fitzgerald himself urged Carmody to “not allow his ambition to subvert his personal integrity”.

Carmody resigned as chief justice after Newman’s election defeat but remained on the Supreme Court bench until September this year. Pointing to the preponderance of Labor appointees — 20 of the 28 Supreme Court trial and appeal judges and 33 of the 42 District Court judges, hardly surprising given how long the ALP has been in office since 1989 — Newman says: “Labor made all the appointments, the people occupying the key positions have a left-wing slant and administer justice from that perspective.”

Queensland Law Society president Bill Potts rejects Newman’s thesis, saying it misrepresents the innate independence of judges. Others point to the appointment to the Supreme Court of barrister Tom Bradley, known as a conservative. That was widely welcomed in legal ranks. “I have to say there has been, generally, a process of picking people not on the basis of their political affinity but because of their skill set,” Potts says.

But the long list of Labor luminaries with handsomely paid government sinecures continues to be targeted by the LNP. It includes former ALP president John Battams as a non-executive director on the board of the Queensland Investment Corporation; former Brisbane mayor Jim Soorley as chairman of state-owned power generator CS Energy; former deputy premier Paul Lucas as chairman of the $5.4bn Cross River Rail project; and former state attorney-general Linda Lavarch as chairwoman of Screen Queensland, among many others.

At the same time, Palaszczuk’s Teflon image has taken a hit from the scandal dogging her factionally powerful deputy and Treasurer, Jackie Trad, over a house purchase made by Trad’s husband in the Cross River Rail development corridor. This week, under the threat of sanction from Speaker Curtis Pitt, her predecessor as treasurer in Palaszczuk’s first term, Trad apologised to parliament for what she insists was an oversight. Many believe that but for the numbers she commands in caucus and cabinet as leader of the dominant Left, Trad should and would have gone.

Instead, she will cast her vote in parliament for a new law recommended by the Crime and Corruption Commission making it a criminal offence for ministers to fail to declare a conflict of interest that could interfere with their duties. “Those issues are not a good look for the people of Queensland when they’re looking at who’s (in) their government,” says LNP leader Deb Frecklington, readying to take on Palaszczuk at the election next October.

Their match-up will be the first between two women vying to be premier. That, perhaps, best demonstrates how far Queensland has come in 30 years.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout