The day Oscar Wilde met Confederate leader Jefferson Davis, and other odd encounters

Strange brushes in history, from Elvis Presley’s curious meeting with Richard Nixon to the duke and duchess of Windsor shaking hands with Adolf Hitler.

As the state of Mississippi narrows and runs out of land – the lower reaches of the river that bears its name and defines its border crudely cut from it by the cartographer’s pen – it arrives at the Gulf of Mexico. The state has just 99km of no-account coastline on which there is a single place of any note: Biloxi.

Jefferson Davis, the slave-owning president of the Confederate States of America who oversaw the south during the civil war, grew up in Mississippi. He was briefly married to the daughter of the 12th US president, Zachary Taylor, but Sarah died of malaria three months later.

Davis later served in both houses of congress and was the 23rd US secretary of war. Later still, he helped forge the 11-state Confederacy that, among other frictions, wished to protect their rights to keep the slaves who were key to the south’s economy. After the north triumphed in 1865, Davis was jailed for two years, but nobody knew what to do with the still-popular leader. He was never charged with war crimes or treason – indeed, he might have been kept in case he could shed light on the assassination of president Abraham Lincoln a week after the war ended. In the end he was permanently bailed for what today would be about $3m, stumped up by prominent southerners.

Broke and unwell, Davis retired to a mansion left to him in a supporter’s will. Beauvoir is a substantial 1845 plantation house on 245ha that once, with the assistance of slaves of course, grew cotton. To this day the home is owned by the Mississippi division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans and houses the Jefferson Davis Presidential Library.

It was here that on Thursday, June 27, 1882 – 141 years ago this week – one of the oddest encounters of the 19th century took place. A tall, handsome, well-spoken and classically educated Irish writer dropped by and stayed the night. His name was Oscar Wilde.

Few men could have had less in common. But how and why Wilde, 25, turned up at 74-year-old Davis’s door is equally odd.

Wilde’s mother, Lady Jane Wilde, was a noted poet and enthusiastic supporter of Irish nationalism. Her brother, John Kingsbury Elgee, immigrated to Louisiana where he became a lawyer and later judge and ardent Confederate; indeed, his signature is on the document with which Louisiana seceded from the Union. Elgee’s son died as a soldier in the civil war.

Many in Ireland identified with the Confederate cause, imagining it was not unlike their wish to be independent of Britain.

Clever and informed, Wilde would have seen through these shallow comparisons, but his famous year-long lecture tour of the US had a commercial core; he was there to publicise his books and plays while – billed as “the English Pre-Raphaelite” – promoting the notion of aestheticism.

And it may have been to his advantage to talk up the exhausted, still ruined south and the failed Confederate ambitions. The crowds that attended speeches would indicate it worked. “Jefferson Davis is the man I would like most to see in the United States,” Wilde told a reporter and then wrote to the former president.

Davis was wary of the ostentatious dandy with a sunflower in his lapel who showed up at his gate. Davis’s wife, Varina, and her cousin were charmed by the brilliant conversationalist, but the deeply conservative Davis, whom Wilde referred to as Jeff, stayed almost silent and politely announced he was unwell and went early to bed. The vainglorious Wilde, whose inner riot of arrogance was never tamed, left an autographed photo of himself as a thankyou for his host. “I did not like the man,” Davis said later.

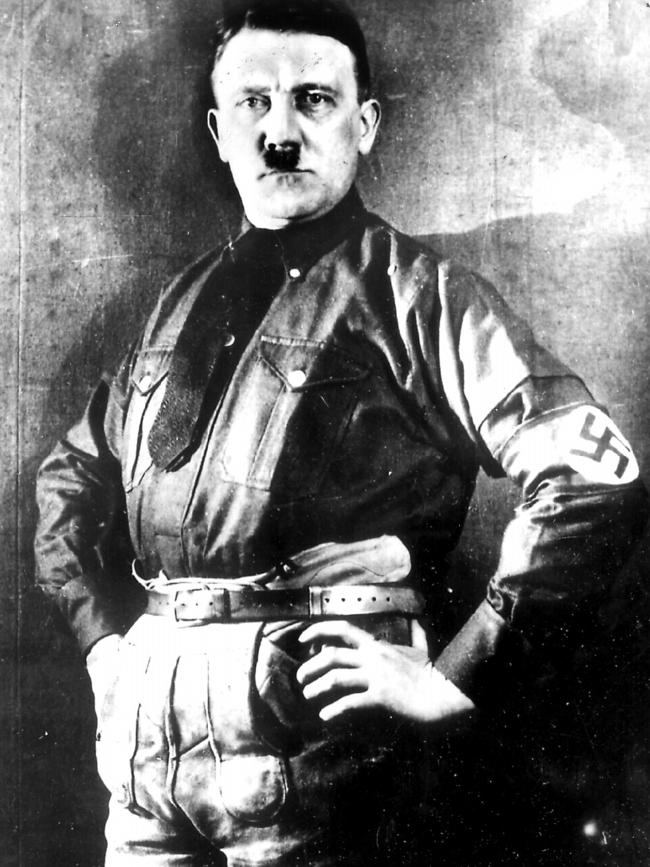

There was no such condemnation of Adolf Hitler after the then duke of Windsor, who less than a year before had been King Edward VIII, toured Germany in October 1937 and arranged to meet its controversial leader, who bowed when shaking hands with the duke. Edward and wife Wallis Simpson, the woman for whom he abandoned the throne, dined that night with Hitler’s friends, Joseph Goebbels and Hermann Goring. Edward made notes of the evening, but these were “lost”.

Many unlikely people met Hitler (but not Winston Churchill, who was a few floors away from Hitler at Munich’s Regina Hotel in August 1932 and was keen, but Hitler judged him to be yesterday’s man and stood Churchill up).

Former British prime minister David Lloyd George visited Hitler in 1936, saying later: “Whatever one may think of his methods … there can be no doubt that he has achieved a marvellous transformation in the spirit of the people”.

But surely the most improbable encounter with Hitler was his accidental meeting with Orson Welles. On January 2, 1939, Time magazine infamously nominated Hitler as its 1938 Man of the Year. Weeks later, and following on from his legendary War of the Worlds broadcast that had some Americans believing the country was under attack by Martians, Welles, just 23, was named American radio’s Man of the Year.

Of course, Hitler ended up frightening more people than Welles, but few suspected anything of the sort when the ever-bold and confident Welles, who had moved to live in Ireland using money left to him by his father, and aged just 16, travelled to Innsbruck to hike the Tyrol mountains.

On his second hike, his young guide, an enthusiastic Nazi party member, told Welles he could arrange for him to attend a rally and dinner that night outside Innsbruck where the guide’s hero, Hitler, would be guest of honour.

Welles believed this was late 1931 or early 1932, and said he went along and was seated next to the soon-to-be-German leader. Welles spoke Spanish and French and may have picked up some German. Hitler had a rudimentary grasp of English. Perhaps that is why he did not say much to Welles, who years later said “he made so little impression on me that I can’t remember a second of it”. He told US TV host Dick Cavett in 1970: “He had no personality whatsoever. He was invisible.”

In 1941, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin al-Husseini, met Hitler in Berlin at a time when Hitler increasingly was receiving few people, and discussed how they would solve their “Jewish problem” after the Fuhrer’s coming victory in Europe. Hitler and the mufti agreed on most things and, in a vulnerable moment, Hitler said the mufti “has more than one Aryan among his ancestors and one who may be descended from the best Roman stock”.

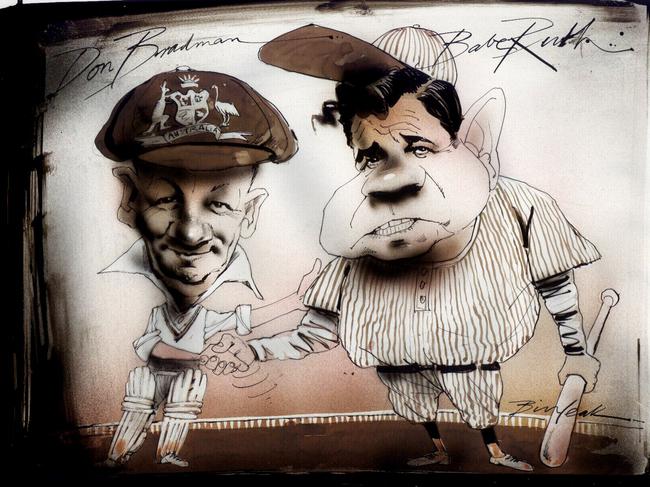

One of the most remarkable of unlikely encounters of last century took place in July 1932 when the short, lithe cricket genius Don Bradman met the hard-drinking, overweight but unrivalled baseball legend Babe Ruth at Yankee Stadium in New York’s tough Bronx neighbourhood. Bradman remains Australia’s greatest sporting hero; Ruth remains America’s.

It was a moment in a now largely forgotten tour of Canada and the US of a team of former and then present-day players organised by recently retired Test bowler Arthur Mailey and sponsored by the Canadian Pacific Railway. Newly married Bradman agreed to join it as long as he could take his wife, Jessie, and it served as a honeymoon for the couple. Matches were played against Toronto, Eastern Canada and even the Hollywood Cricket Club in Los Angeles, whose members included Cary Grant and skilled wicketkeeper William Pratt, otherwise known as Boris Karloff.

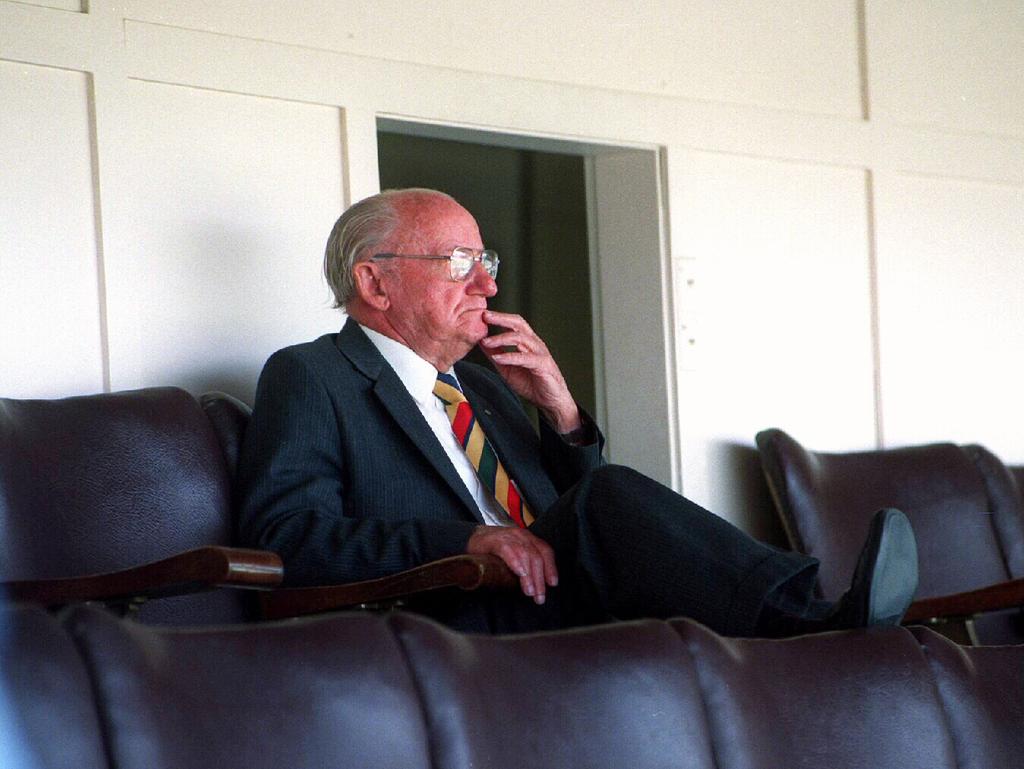

Bradman met Ruth when the tour landed in New York. Ruth was injured and sat in the stands. It was July 1932. “From what they were telling me, I thought you were a husky (big) and strong guy,” Ruth was reported to have said to Bradman. “But us little fellows can hit them harder than the big ones.’’

Bradman told Ruth he should try out cricket one day, and three years later in London he did. Told how much cricketers were paid, he vowed to stick with baseball, a game Bradman found attractive.

“In two hours the match is finished. Each batter comes up four or five times. Each afternoon’s play stands on its own. Yes, cricket could learn a lot from baseball … There is more snap and dash to baseball,” he told a reporter.

Ruth died aged 53, just two days after Bradman was bowled for a duck at The Oval to end his career on August 14, 1948.

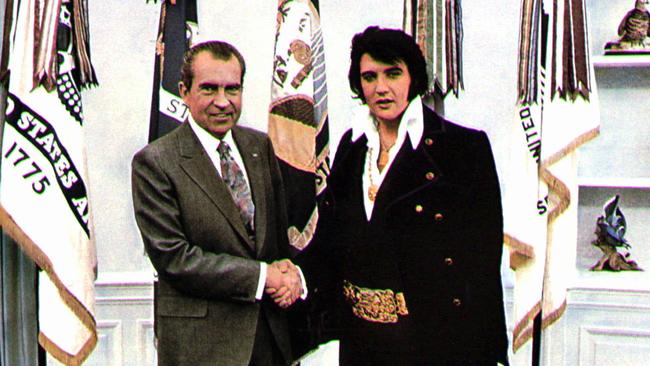

A celebrated odd coming together was that of Elvis Presley and US president Richard Nixon. On a flight from Los Angeles to Washington, DC, on December 20, 1970, Presley got talking to California senator George Murphy. Presley would have known that Murphy had been a big name in Hollywood musicals during the war years. He’d been president of the Screen Actors Guild, taking over from James Cagney in 1944. Overseeing entertainment at presidential inaugurations, he had become friendly with fellow Republican Nixon.

Presley told Murphy he hated drugs and wanted to be appointed a special agent of the Bureau of Narcotics. And he wanted to meet the president. Murphy, with just days of his term left, flippantly told the singer to write to Nixon. Presley hand-wrote a six-page letter to the president on the plane and had his limo driver drop by the White House, where Presley personally dropped it off. Presley included his phone number at the hotel where he was booked in under the name Jon Burrows.

Hours later Presley was being photographed in the Oval Office with an awkward Nixon, who presented the King of Rock ’n’ Roll with the much-sought Bureau of Narcotics badge. The meeting was kept a secret until news of it was published in 1972. That photograph remains the most requested from the US National Archives.

But the meeting was uncomfortable for the president, who agreed to it only because it might make him “more popular with the kids”, knowing an upcoming amendment to the US constitution would mean 18-year-olds could vote at the next presidential election. Presley arrived at the Oval Office in a purple velvet suit with large cufflinks the president admired, adding: “You dress kind of strange, don’t you?”, to which Presley replied, “You have your show and I have mine.”

Presley then wandered off on a rant against the Beatles, who he believed were anti-American. “They came over here. Made a lot of money. And then went back to England. And they said some anti-American stuff when they got back.” The young aide who took notes of this conversation said Nixon appeared not to know what Presley was talking about.

But it was Nixon who tried to have John Lennon expelled from the US after the former Beatle went to live there permanently in 1971 and then campaigned against the Vietnam War and the re-election of Nixon in 1972. When Lennon, who also was interviewed by Cavett, told the television audience of millions that the FBI was spying on him, few believed him. Years later it was revealed to be true.

None-too-smart former Chicago Bulls basketball star Dennis Rodman is well known for two facts: he claims to be the oldest of 47 children – and he is best friends with murderous North Korea’s Supreme Leader, Kim Jong-un.

Last weekend, more than 120,000 North Koreans marched to commemorate the 73rd anniversary of the Korean War that started when the North invaded the South. The smiling protesters bore flags with slogans such as “Let’s eradicate US imperialist invaders”. But Rodman appears to believe the imbalanced, nuclear-armed dictator is a trusted mate.

Kim invited his sporting hero to Pyongyang in 2013 and, after hugging, Rodman said: “You have a friend for life.” The basketball star was back the following year to sing Happy Birthday to Kim. About that time Kim started killing family members, including his uncle and nephews. An associate of his uncle was assassinated with a flamethrower, and in 2017 Kim had his half-brother assassinated at Malaysia’s Kuala Lumpur airport.

But Australian George Hubert Wilkins might trump them all. He lugged a bulky Gaumont camera on to the battlefields of World War I and photographed the fighting that raged around him. Bemused Germans dubbed him “dieser verruckte Fotograf” – that mad photographer – and discussed if they should shoot him.

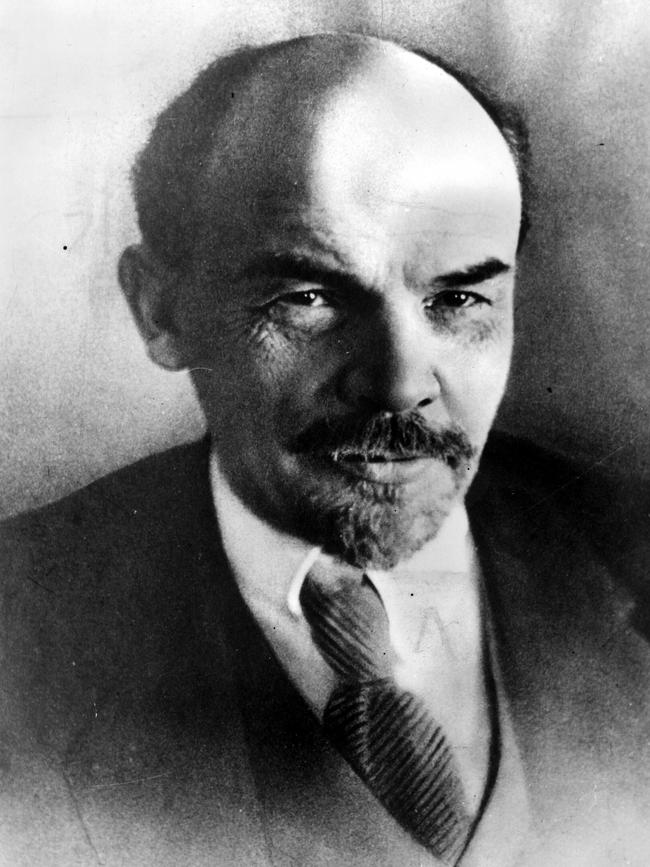

In an extraordinary life of adventure he flew over the North Pole, joined Ernest Shackleton’s doomed voyage to South Georgia, crossed the Atlantic in the Graf Zeppelin and was first to voyage beneath the Arctic ice in a submarine. On the way he met Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, Walt Disney, King George V – who knighted him – and Vladimir Lenin, who discussed with Wilkins the slow economic development of his homeland – reportedly becoming the last Westerner to meet the revolutionary communist leader.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout