The currency of class

In today’s Australia there’s a disconnect between incomes and our own perceptions.

Ask Matt Hearn to describe his class and he has to stop and think. “If pressed I’d say middle class, maybe,” the bricklayer says. “It’s a bit hard to say. I’ve never really thought about it.”

Hearn is 28, has a bricklaying business that employs five others and pays himself just short of six figures. Engaged to his business partner, Tiffany Newton, he has just moved into a new home in Bacchus Marsh on Melbourne’s outskirts and is having an investment property built nearby. He went to a private school, flirted with an office job in accounting but loved working outdoors too much. The young couple’s business is extremely busy and they plan to move into property development.

Property director Sarah Case is unequivocally middle class, she says. Case, 41, grew up in a country town, both parents running separate small businesses, with a hardworking family ethos. She has worked hard all her life and now lives in Malvern in Melbourne’s eastern suburbs. She is married and has a son, and her household income sits within the top 10 per cent of Australian households, but she says they still feel the cost of living squeeze.

“Even if we became really wealthy, I would always consider myself middle class,” Case tells The Weekend Australian.

Middle-class calculator: see where you rank on the socio-economic spectrum

A brickie in the middle class, a property director with a big family income in the middle class. Australia has a complicated relationship with class.

The Weekend Australian’s exploration of what it means to be middle class in today’s Australia finds a disconnect between objective measures of middle class and our own perceptions.

Social media sway

At the top end, very few Australians are prepared to call themselves upper class despite having high incomes. And at the other end many continue to identify as working class even though they earn enough to be considered well into middle class among developed economies.

Many high-income Australians know they are doing relatively well but still feel pinched by housing, education and health costs. They tend to be surprised to discover their income is towards the top end of the nation’s income spectrum. They may believe others among their peers are doing better, going on better holidays, driving nicer cars, while they can’t do some of the things they want to.

For those who identify as working class, history and family may be a stronger influence than a salary that pushes them into the middle income ranks or even higher.

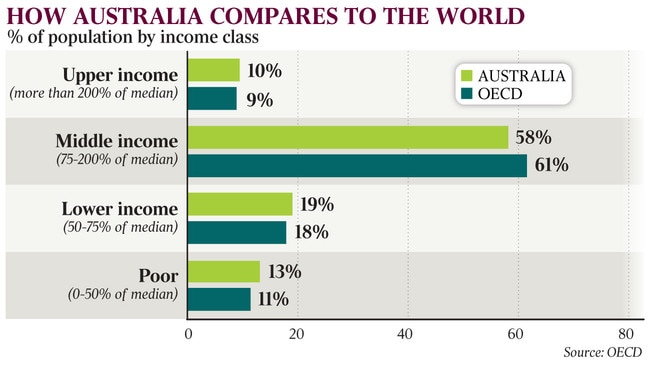

An OECD report, Under Pressure: The Squeezed Middle Class, published in April, offers a comparison of middle-class incomes across the developed world. It defines middle class as households with disposable (after tax) income of between 75 per cent and 200 per cent of the median income. In Australia’s case that is after-tax income of $33,300 to $88,700 for a single person and $66,600to $177,400 for a couple with two dependent children.

On this measure, 58 per cent of Australians are ranked as middle class, slightly lower than the average across developed economies of 61 per cent. One in 10 Australians fits within the upper income band (compared with 4 per cent in Denmark, as an example), and 32 per cent sit below, slightly higher than the OECD average.

Contrast this to how Australians rate themselves by class. In his paper Class, Capital and Identity in Australian Society, social policy researcher Nicholas Biddle surveyed 1200 Australians on class identity. Biddle says he was surprised only 72 didn’t answer this part of a longer survey. “This did interest me given the supposed predisposition against class identification in Australia,” he tells The Weekend Australian.

Biddle’s survey finds only 2 per cent of Australians identify as upper class, with 57 per cent calling themselves middle class and 41 per cent working class.

Setting this against the OECD numbers, the proportion of Australia’s middle class is similar at just under 60 per cent, but there is a marked disparity on either side. There are five times more high-income earners on the OECD numbers than people identifying in Biddle’s work as upper class. And there are far more people identifying as working class in Biddle’s survey than on incomes below the OECD’s middle income range. So why the disparity?

Biddle, associate director at the Australian National University’s Centre for Social Research and Methods, says even high-income households, if disposable income is squeezed, will be affected in terms of class perceptions.

“The more you think your income will have to be spread across meeting your basic needs, the less likely you are to feel you belong in those upper-class echelons,” he says. “And the less likely you are to feel you are in the class status that your income predicts.”

Case says her household definitely feels this pinch. “With interest rates low, the mortgage is manageable,” she says. “It is the rising cost of living with utilities, fuel, school fees and general consumables for all families that puts the pressure on.”

Biddle says social media skews people’s perceptions of status, even class. “When we see other people’s holidays on social media we don’t know what they have forgone to take that trip. All we see are the beautiful pictures. We know what we’d be giving up to make such a trip, but we forget about that for them. This may make us feel less affluent than someone we thought was on an economic par with us and, in turn, potentially affect our own perceptions of class.”

Imogen Randell, chief executive of Quantum Market Research, a consumer research and cultural trends agency, says people tend to judge themselves against their own immediate tribe and like to sit in the middle of that tribe. That is why there is a predisposition for higher income earners to identify as middle class.

“We talk to a lot of people and cost of living is raised all the time, even by those on household incomes of $150,000,” Randell says. “They say they are struggling, but they are really struggling within that group. The costs that concern them are mobile phone bills, but they want a new phone every two years. And there’s private health insurance, power, rates, all of which cost more if you have more.”

Former Productivity Commission chairman Peter Harris agrees. Being middle class, he suggests, depends less on what you earn and more on what you spend it on.

“Consumption is important as it’s the outcome that matters, not the input, when it comes to considerations of middle class,” he says. “If you spend your income on travel and cars, that spending is affording you a better lifestyle, which in turn affects your own perception about being a middle-class citizen. If your money is more tied up in housing, it isn’t contributing to your lifestyle to the same degree.”

Family factors

Of course, income is only one marker of class, and a rough proxy at that, despite the OECD report. Other factors are at play: our work, family history, aspiration, age. And where it fits at all in Australian life is part of the debate, particularly compared to other countries.

Hearn says discussions of class haven’t featured heavily in his life. “My dad works on big construction jobs and as a family we did pretty well. But we didn’t talk about money growing up and we didn’t talk about what class of society we were.”

He says tradespeople tend to have an egalitarian approach to life. “There’s a different vibe than in an office. Trades rely a lot on teamwork. If you don’t bond it doesn’t work. But we don’t talk about things like class. We know we’ve just got to do what we need to do to make ourselves happy.”

Case says her family background is a huge factor in her world view. “I grew up in a small country town where the perception of class and class division was not really around,” she says. “Down in the Western District (of Victoria) everyone works very, very hard. It’s tough, so class isn’t really a thing.

“Dad owns concrete plants and is nearly 72 and still working six or seven days a week. He drives an old Range Rover in his Hard Yakka shorts and shirt, muddy boots, and is always dusty with concrete all over him. He’s a perfect example of why.”

Randell says we are likely to ascribe our class from our family history and roots.

“Wherever we were born, we are usually pretty comfortable to identify with that,” she says. “We don’t have that same aspiration that people in the US do to break away from family origins, that ‘you can be whatever you want to be’ attitude. We don’t have the same impetus. For us it is more about being down to earth and approachable. Our richest are often found dressed in T-shirt and shorts.”

Harris agrees Australians don’t have that same desire to elevate their status in society or their class. “We don’t have that same self-perception of being ‘on my way to the top’. That idea that anyone can be president is absolutely real in the US, but not of as much interest in Australia.”

There are considerable economic and political tensions built around Australia’s middle class. Much is made of policy aimed at Australia’s middle class, of middle-class welfare, of the quiet Australians and the big end of town.

In March former prime minister John Howard talked about how it remained the goal of many Australians to be middle class. Referring to a Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report from October last year that put Australia first among developed countries for median wealth per adult, at $US191,450, Howard said any narrative about growing inequality in Australia was demonstrably off beam.

“These figures don’t suggest inequality is growing at all,” he told this newspaper at the time. “One of the things that hasn’t fundamentally altered is that we are still a very middle-class society … we are still the biggest middle class (per capita) in the world and people aspire to the middle class.”

ANU’s Crawford School of Public Policy social policy researcher Peter Whiteford says the Credit Suisse figures are built around high levels of wealth associated with housing in the big capital cities and that in reality the economic influence of the middle class and its role as a “centre of economic gravity” has weakened.

“Overall, median incomes have increased a third less than the average income of the richest 10 per cent. And the cost of essential elements of the middle-class lifestyle, especially housing, have increased faster than inflation,” he says.

Harris acknowledges there has been faster growth for the top 10 per cent of wealth holders in Australia, but says at the same time all levels of income have been rising, which is not the same for most developed economies.

“The key reason for this is our compulsory superannuation system. Even most of our poorest, provided they are working, have some level of super, and this is why it’s fair to say all boats are lifting in Australia,” Harris says.

Whiteford says superannuation has lifted many boats, but not all. “Those of working age outside the labour force and jobless households obviously don't benefit anywhere near as much as those with stable jobs. Excessive charges including for insurance that you don’t know about and multiple accounts undercut the effectiveness of superannuation for some lower-paid workers.” He says broad demographic changes in how we work are part of the class story. “Class is partly about how you define yourself, but also about the types of jobs that people do,” he says. “Occupational structures … have changed enormously since the 1970s. The other major change is in the employment of women.”

Workplace trends

The OECD report tells a similar story, finding that since the mid-90s the proportion of low-skilled jobs has fallen slightly from about 20 per cent to 16 per cent of the workforce. For middle-skilled jobs the decline has been steeper, falling from 45 per cent to just over 30 per cent of the workforce. In the same time the proportion of high-skilled jobs has risen from 33 per cent to more than 50 per cent.

“These are really very large changes over recent decades, which means how people think about their current and future status is also likely to have changed significantly,” Whiteford says. “For example, my rough calculation is that in 1966 about 95 per cent of men of working age were employed — and probably mostly full time. The employment rate of working-age men is now about 79 per cent, and a much higher share are part time.

“I think that it is also worth noting that manufacturing employment — which is close to the archetypal working-class job — has declined significantly. In 1966 about 30 per cent of male employment was in manufacturing — now less than 5 per cent of total employment is in manufacturing (it would be a bit more for men).”

Additional reporting: Remy Varga

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout