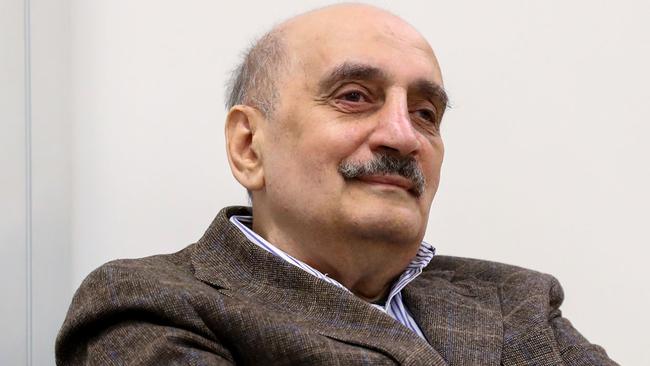

Soviet-era dissident Sergei Grigoryants took on Putin’s Russia

Sergei Grigoryants was bashed and lost an eye, was hit by a car, his son died mysteriously, but he kept trying to expose corruption in Russia.

OBITUARY

Sergei Grigoryants Dissident.

Born Kyiv, Ukraine, May 12, 1941; died Moscow, March 14, age 81.

-

Opponents of Vladimir Putin have long been aware theirs is among the most dangerous jobs on Earth. They are harassed, jailed, assaulted, exiled and fall out of windows. Many are assassinated.

The rollcall of brave dissidents who have criticised Putin’s leadership and been murdered is depressingly long and includes: Boris Nemtsov, a former deputy prime minister, was shot; Alexander Litvinenko was poisoned in London; exiled Boris Berezovsky was found dead at home in England; journalist Natalia Estemirova was kidnapped and shot; Stanislav Markelov and Anastasia Baburova were shot near the Kremlin; campaigning reporter Anna Politkovskaya was arrested, subjected to a mock execution, later poisoned, then shot dead in her apartment on Putin’s 54th birthday.

To be fearless and bold in Putin’s Russia is a big call.

Sergei Grigoryants made that call and his family suffered uniquely for it over many years.

He first studied with a view to becoming an aviation engineer but travelled to Moscow to pursue journalism. By the early 1970s he was enthusiastically involved in the samizdat movement. This evolved to overcome a Soviet Union system that registered and licensed all typewriters and printing equipment. This was so tightly enforced that from every typewriter made in Russia a sample was taken of its script – like a fingerprint – which was kept and compared with dissident posters and bulletins.

So newsletters were handwritten and passed from hand to hand. In other cases, books banned by Soviet authorities, such as Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago, were bound in the covers of acceptable books and handed on.

In 1975, Grigoryants, who had been critical of the KGB secret police that he thought manipulated a government less powerful than the average Russian believed, was jailed for five years but kept behind bars for seven. Released in 1982, he published newsletters describing how human rights were a fiction in his country. Charged with the crime of spreading anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda he was rearrested in 1984 and sentenced to 10 years hard labour at a corrective colony.

Soon after, Mikhail Gorbachev became the supreme Soviet Union leader – its last. In Gorbachev’s era of glasnost, Grigoryants was freed in an amnesty and he immediately started a news publication, of course called Glasnost. He still had the KGB in his sights. And they him. About then, Putin had risen to be a lieutenant colonel in the KGB. He would leave for politics, but later would serve as director of its successor, the Federal Security Service (also reportedly closely allied to organised crime) and even secretary of Russia’s Security Council.

Grigoryants’s office was regularly raided and his computers confiscated. Sometimes he was beaten, once so severely he lost an eye. He would tell journalist friends that Gorbachev and his successor Boris Yeltsin might talk of perestroika, but behind them, and feared by them, the KGB was retaking control and threatened the nation.

By 1989 he was one of his country’s most prominent dissidents, and that year the World Association of Newspapers awarded him its Golden Pen of Freedom.

He was critical of what became the First Chechen War, and during it, in January 1995, his 20-year-old student son Timofei was killed in what officially was a hit-and-run accident, but witnesses claimed they saw Timofei’s body being thrown from the car.

Grigoryants’s wife and daughter fled to France. He drove them to the airport. In 2010 he told a BBC interviewer what happened when he returned home and his doorbell rang. Through a peephole he saw three burly young men

“They tried to persuade me to open the door, saying that somebody … had suggested that they ask me for help with a problem they had. I said they could call me from the pay phone downstairs … I wouldn’t open the door.”

The men kept negotiating with him, but interestingly they didn’t try to force their way in. Perhaps they had been made aware that Grigoryants had strengthened it with reinforced steel: “It would have been difficult to smash it without attracting attention.

“I have no doubt that if I had opened the door, they would simply have chucked me out of the window. It wouldn’t have looked suspicious, a man committing suicide after his son dies, and his wife and daughter go to live abroad.”

In 2018 he was mysteriously hit by a car on a Moscow street.

Grigoryants was still active and had several books in the works, including an investigation into the influence of the FSB, when he died suddenly last week of unknown causes.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout