Solomons-China security deal a nightmare in paradise

The bombshell Solomons-China security deal lays bare the limits of diplomatic clout wielded by Australia, NZ and the US in the face of a China determined to gain a strategic foothold.

“If you look and if you ask me, where are the places where we are most likely to see certain kinds of strategic surprise – basing on certain kinds of agreements or arrangements, it may well be in the Pacific,” Campbell said in January.

Campbell’s worst fear – and Australia’s – has now been realised with the bombshell plan agreed on Thursday by Solomon Islands to enter into a security agreement with China.

The deal, which could eventually see Chinese troops and ships based in the island nation less than 2000km northeast of Australia, poses a giant strategic and diplomatic dilemma for Canberra. It lays bare the limits of the diplomatic clout wielded by Australia, New Zealand and the US in the South Pacific in the face of a China that is determined to gain a strategic foothold in the region.

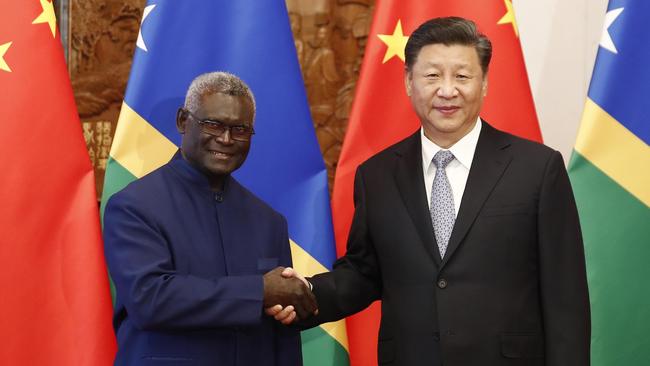

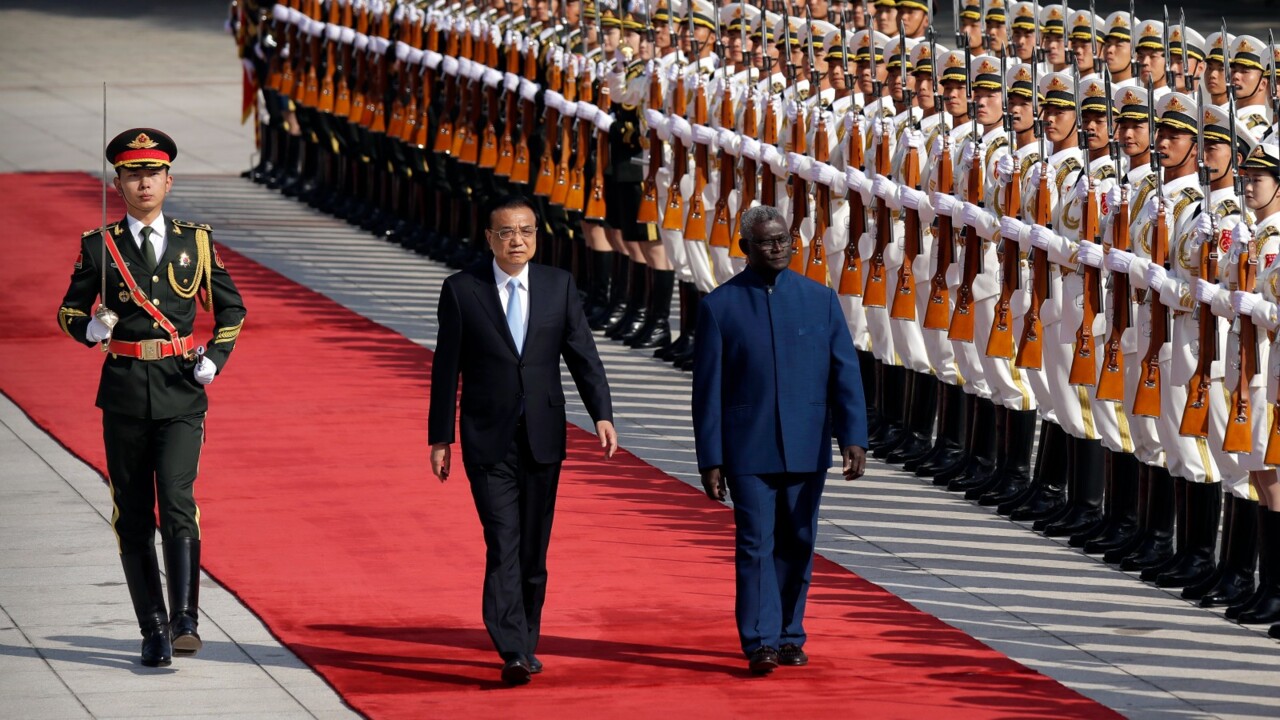

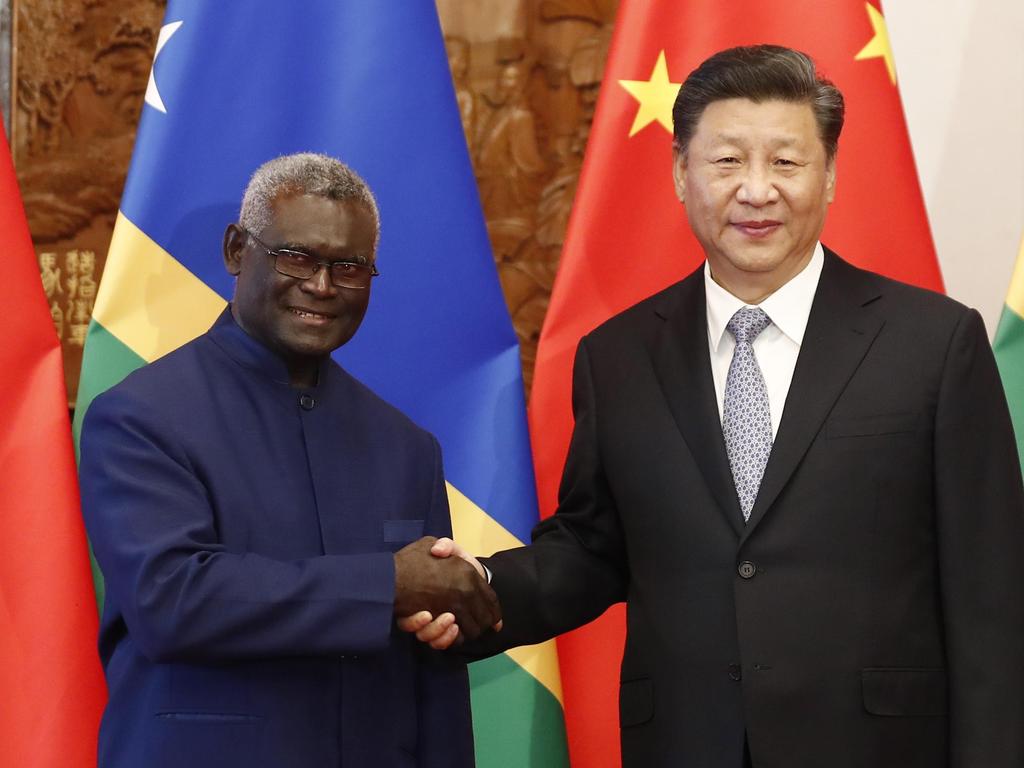

And it begs the question of what more Australia can do to win the loyalty of those Pacific island leaders – such as the volatile Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare – who are willing to exploit geopolitical tensions to play Canberra off against Beijing?

“Australia is right to be very concerned about this agreement because any security agreement between Solomon Islands and China changes the regional order,” says Mihai Sora, a Pacific Islands expert with the Lowy Institute who served as an Australian diplomat in the Solomons.

“What the agreement does is shed the veneer that Chinese interest in the Pacific is purely economic,” says Sora.

“It reveals their strategic intent and their aspirations to project force and as such it has the potential to really occupy Australia’s strategic attention.”

The Solomons-China security deal, which has been “initialled” by the two countries and awaits signing by their respective foreign ministers, will be the most significant victory yet for Beijing in its campaign to win the hearts and minds of South Pacific island nations and dislodge their traditional alliance partners, Australia, New Zealand and the US.

Although the Australian government admits it has known of the proposal for a Solomons-China security deal for some time, it did not know how to respond to it. If Canberra responded aggressively about the deal it would have looked paternalistic and could have pushed Sogavare further into China’s camp.

In the short term, there was little Australia could do to stop this deeply disturbing development. Sogavare’s fiery speech this week to parliament showed just how determined he was to pursue this deal.

“We welcome any country that is willing to support us in our security space,” he told parliament. “There is no devious intention, nor secret plan. This is a decision by a sovereign nation that has its national security interest at heart.”

In an apparent broadside at criticism from Australia and other allies, Sogavare added: “We find it very insulting to be branded as unfit to manage our sovereign affairs or to have other motives in pursuing our national interests.”

The exact nature of the final deal remains unclear, but a leaked draft says it would enable the Solomon Islands government to “request China to send police, armed police, military personnel” to the country, and for Chinese ships to visit and “carry out logistic replenishment”.

Sogavare claims his government has “no intention whatsoever to ask China to build a military base” but experts say any such deal would theoretically open the door to a Chinese base in the future.

Such a base would give Beijing unprecedented ability to eavesdrop along Australia’s eastern coast, monitor naval and air force movements and – in a time of conflict – disrupt communications and supply lines. As Peter Jennings, head of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, put it: “We could in 15 years see People’s Liberation Army maritime surveillance aircraft using Honiara to keep a permanent surveillance cap over our east coast … a Chinese military base in Honiara crosses a line that Canberra cannot permit.”

But, equally, there was no easy way to stop it. Australia has done more than any other country to help Solomon Islands overcome its long history of volatility and ethnic violence. Between 2003 and 2013 Australia sent more than 7000 troops, police and personnel as part of the multi-country peacekeeping mission in the island nation.

Australia remains easily the largest aid donor, giving $170m a year to Solomon Islands, and late last year it deployed 200 police and soldiers to Honiara to help restore order after deadly riots. Some 50 Australian Federal Police members remain there and will stay until 2023.

In this week’s federal budget Australia committed to spending $65m for a new high commission in Honiara.

The US has also stepped up its engagement with Solomon Islands, with Secretary of State Antony Blinken this year announcing the US would reopen an embassy there after closing it in 1993. But none of this has bought the loyalty of the Solomons government.

Sogavare has refused to turn his back on China, which has relentlessly pursued closer ties with his government. In 2019, amid rumours of Chinese pay-offs for MPs, Sogavare’s government ditched diplomatic recognition of Taiwan in favour of Beijing.

During last year’s riots, triggered by divisions over that recognition of Beijing, Sogavare also accepted Chinese offers of police and aid to help restore calm.

Although Australia is the biggest aid donor, China has leveraged the fact that it is easily the island nation’s most important trading partner. China takes 67 per cent of Honiara’s exports compared with Australia, which is ranked in 13th place with just 0.9 per cent of goods.

Solomon Islands maintains its foreign policy is to be “friends to all, enemies to none”. But it is also exploiting the geostrategic interest from Australia and China for its own gain.

“There is an element of the Solomons government seeking to maximise the benefits to itself from this increased global attention,” says Lowy’s Sora.

“Sogavare has been really hot and cold about Australia’s presence in the Solomon Islands for some time. It is obvious that he doesn’t want the Solomon Islands to be beholden to a single security relationship, namely Australia.”

With a federal election looming, Labor has portrayed the China security deal as a foreign policy failure, blaming the Morrison government for not doing enough to stop Honiara from embracing Beijing.

Labor foreign affairs spokeswoman Penny Wong describes the security deal as “gravely concerning”.

“Scott Morrison talks tough on China, but on his watch a member of our Pacific family plans to sign a security treaty with China,” she says.

So what more can Australia do, not just in the Solomons, but across the South Pacific, to counter China?

In 2018, with a wary eye towards Beijing, the Morrison government announced it would “launch a new chapter in relations with our Pacific family” through its so-called Pacific Step-up.

This involved establishing new diplomatic missions across the region, new security partnerships and a blizzard of new programs, ranging from disaster resilience to economic growth to undersea cables.

“The Pacific step-up was significant relative to the preceding years,” says Sora.

“But governments on both sides of politics have waxed and waned in the attention they give to the Pacific at the top political level.”

The leaking of the Solomons-China draft agreement coincided with Australia pledging an extra $20m in support for the island nation as well as a radio network across the islands, a new patrol boat outpost and an extended stay for AFP personnel there.

But some aspects of Australia’s commitment to the region are mixed. In this week’s budget, the government lifted aid funding to the Pacific region to $1.85bn in 2022-23 and doubled the Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific to $3bn.

Yet it cut funding for defence co-operation with regional partners from $236m to $227m at a time when China is negotiating a security deal with the Solomons and seeking other strategic footholds across the Pacific.

“I don’t think there is much that Australia could have done to stop the security deal,” says Graeme Smith, a senior fellow in the ANU’s department of Pacific affairs. “The current Prime Minister of the Solomons is very set on it. I think it really says more about the Solomon Islands than it does about China.”

Smith believes the security deal may last only as long as Sogavare’s government. “I think if he got kicked out, it would join a very full graveyard of Pacific-China MOUs which have never been acted upon.”

Smith also believes any security deal would only lead to the Solomons becoming a refuelling and logistics port for China, rather than a fully fledged military base. “I don’t see a base in the Solomons because sovereignty is a very serious issue there, not just for the government but for the people.”

Even so, the security deal represents a dangerous precedent at a time when Australia is engaged in an increasingly intense proxy battle with China for influence across the South Pacific.

China has steadily increased its economic aid and investment to the Pacific Islands over the past 15 years, providing $US1.5bn in foreign aid between 2006 and 2017 through a mixture of grants and concessional loans.

Beijing has been accused of using “debt trap diplomacy”, by providing loans it knows island nations will struggle to repay, thereby increasing Beijing’s future clout with those governments.

China provided 8 per cent of all foreign aid to the Pacific Islands between 2011 and 2017, although this is still a distant second to Australia and New Zealand, which together comprise around 55 per cent of all aid to the region.

However, China’s aid and investment have focused on large and very visible infrastructure projects, from roads and bridges to sports stadiums and schools.

This year, the simmering Australia-China rivalry in the Pacific burst into rare public view in January when an underwater volcano triggered a deadly tsunami in Tonga.

Australia dispatched a navy ship and humanitarian aid, only to be matched days later by China, which sent two navy ships and 110 pieces of machinery such as bulldozers to begin “national reconstruction” of the island.

In Papua New Guinea, Fiji and elsewhere in the Pacific, Australia and the US have launched a raft of initiatives and investments to counter China’s growing influence.

Blinken this year became the first US secretary of state to visit Fiji in 36 years and in 2021 Biden became the first US president to address the Pacific Islands forum.

“What happens here (in the Pacific Islands) matters to the United States. We share a history,” Blinken said. “It was here on these beaches that Americans braved some of the hardest-fought battles of the second world war.”

China argues that the US and Australia are seeking to destabilise the Pacific and that their attempts to win the support of island nations are driven by anti-Chinese sentiment.

Beijing has lashed out angrily at criticism of its security deal with the Solomons, saying Australia and others are behaving “self-importantly and condescendingly”.

“Any attempt to disrupt and undermine mutually beneficial co-operation between China and Pacific island countries is doomed to fail,” China’s Foreign Ministry spokesman, Wang Wenbin, said.

It remains to be seen whether Australia’s worst fears about the Solomons-China security deal are realised.

But the events in Honiara this week have underlined a grim truth about Australia and its so-called Pacific Family.

You can be neighbours with a shared history. You can be the largest donor of aid and assistance. You can even provide police, troops and naval vessels. But none of this guarantees that Australia will outflank Beijing to win the hearts and minds of Pacific Island nations.

Joe Biden’s top adviser on Asia, Kurt Campbell, warned recently that an unwelcome “strategic surprise” in the Pacific had become his greatest fear.