China-Solomons pact is a disaster for Australian security in the South Pacific

It is a bad, perhaps disastrous, development for our security. New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern has for once got a strategic assessment right when she described the agreement as “gravely concerning”.

Australia’s intelligence agencies have known for years that Beijing has a serious ambition to establish a full military base in the South Pacific. There have been previous efforts with Vanuatu.

The Chinese are all over the South Pacific. Beijing’s embassy in Fiji is one of the most imposing buildings in Suva.

Aid, trips, subsidies, development of shonky infrastructure which more fastidious countries wouldn’t fund – the Chinese are making a huge effort in the South Pacific.

Once, this Chinese effort was designed to seduce some of the few remaining nations that still maintained full diplomatic relations with Taiwan.

Now, Beijing’s purpose is to intimidate Australia and limit the options of the US.

It was a key war-time aim of Japan to isolate Australia from the US by occupying Pacific territories, specifically Guadalcanal in what is now the Solomons.

A Chinese military base in the Solomons can develop in many clandestine ways. It can in time project the full array of naval force, host electronic listening capabilities, receive the “grey zone” fictionally civilian vessels that Beijing uses to conduct much of its regional coercion, store munitions and much more.

China’s President Xi Jinping famously promised former US president Barack Obama that China would not militarise the South China Sea. Beijing now has 22 points of military presence in the South China Sea, including military air fields and the like.

Nor would a base in the Solomons be the limit of Beijing’s South Pacific ambitions. In Papua New Guinea, it has made big political inroads and has ambitious plans for PNG resources.

It is possible no Australian government could have stopped this development. China is a determined, rich and powerful super power, and it is relentlessly determined to increase its South Pacific power.

It has advantages over countries like Australia and New Zealand. It can throw money around far more indiscriminately, both infrastructure and other aid money, and sponsorship that finds its way directly into the pockets of politicians or officials.

However, the Australian and general Western effort in the South Pacific has on its own terms been sub-optimal.

It is ridiculous to think the unwillingness of Canberra leadership to mouth the same platitudes as South Pacific leaders on climate had any effect on this. Beijing did not attend the last climate summit and is the world’s biggest polluter.

Nonetheless, the Chinese-Solomons agreement does represent a failure in diplomacy and strategic policy.

The Solomons is one of the least-developed and most divided nations in the world, with a seething hostility between the Malaita province and Guadalcanal. Its politicians are long accustomed to auctioning their support between China and Taiwan.

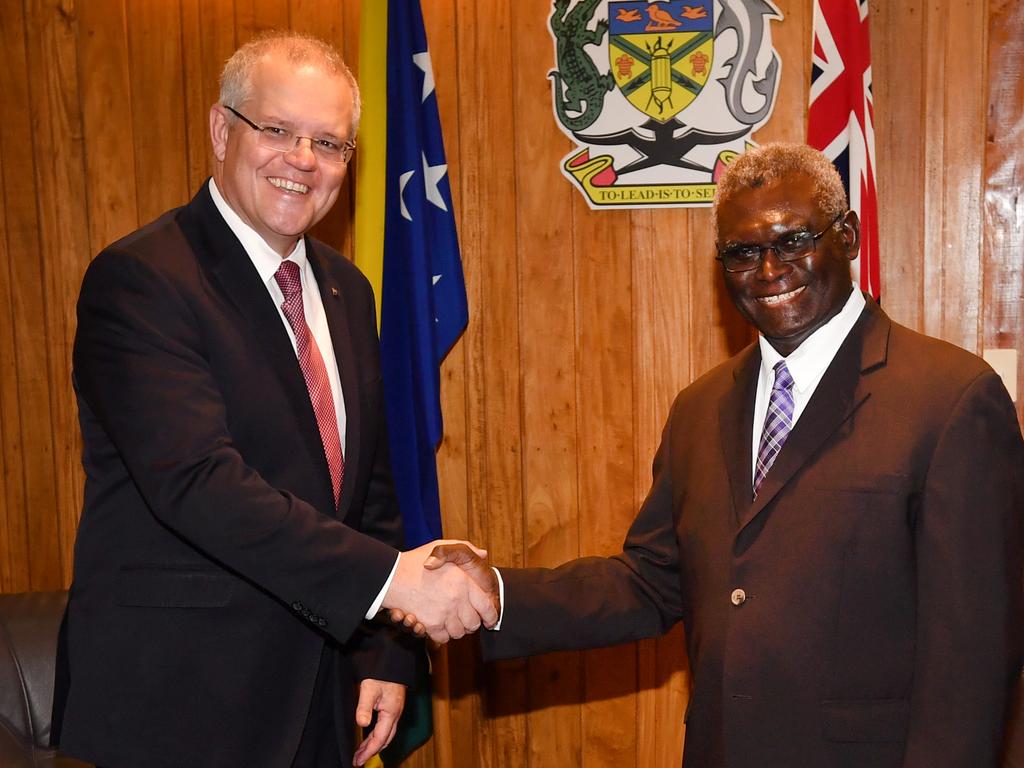

Sogavare complains bitterly that it is shocking and insulting to be regarded as incapable of deciding his nation’s strategic interests, yet only a few months ago it was necessary for the Morrison government and other South Pacific governments to send, at the PM’s request, soldiers and police to put down deadly riots in Honiara.

Our intervention helped keep Sogavare in power, but it certainly didn’t earn us much influence. Nor have the hundreds of millions of dollars of aid Australia has poured into the country.

Given Sogavare’s fiery speech in parliament, it will be very difficult to talk him out of signing this agreement. Beijing will do everything it can to ensure the agreement comes to life.

Yet many of China’s Belt and Road Initiative agreements have failed to result in meaningful action.

Canberra was unable to prevent this development that is so contrary to our interests. The object of our policy now should be to convince the Honiara government that it does not need anything the agreement notionally provides for.

There is a lot of opposition within the Solomons. And it may have woken Wellington from its strategic torpor, in which it refused to even acknowledge strategic competition in the region.

As well, the US is becoming more active. It is a further failure of Australian policy that we had not, until five minutes ago, been able to talk Washington into maintaining an embassy in the Solomons.

The Biden administration’s Asia policy co-ordinator, Kurt Campbell, has said the South Pacific is the part of our region most likely to furnish “strategic surprise”. Washington and Canberra both need deeper involvement.

The security agreement between Solomon Islands and China, so savagely defended by Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare in parliament this week, represents unequivocal failure for Australian policy.